Emerging markets cut reliance on foreign bank credit

Trend should help developing countries withstand global shocks

Major emerging markets have become less reliant on foreign bank capital since the global financial crisis, reducing the risk of contagion from credit crises elsewhere.

However the remaining foreign bank credit tends to be sourced from a narrower range of countries, raising a red flag for some economies, particularly in Latin America, according to new research from the Bank for International Settlements.

The findings are important given the role foreign banks played in helping to power the pre-financial crisis credit booms and post-crisis busts seen in some emerging economies.

Academic work has also pointed to the role that foreign banks, particularly Japanese ones, played in spreading the 1997 Asian financial crisis from Thailand to Indonesia, Malaysia and South Korea by “drastically” curtailing their lending. This and other EM crises have been exacerbated as foreign banks withdraw their capital in times of distress.

“Unexpected losses in one country may induce banks to withdraw from other borrower countries as banks restructure their asset portfolio in an attempt to rebalance overall risks and satisfy regulatory constraints,” the BIS, commonly known as the central bankers’ central bank, said last year.

“Local funding has proven to be more stable through financial crises, while cross-border and foreign currency funding has been less so,” said Bryan Hardy, a BIS economist and author of the new research.

Foreign bank credit to the non-bank private sector in 17 major emerging economies rose sharply in the run-up to the global financial crisis from $310bn at the end of 2004 to $1.47tn in mid-2008, the analysis found.

It subsequently fell to a low of $1.26tn in early 2009 and has since risen modestly to $1.54tn as of last year. However, lending by both domestic banks and “non-banks”, such as bond investors, has risen far faster, as shown in the first chart.

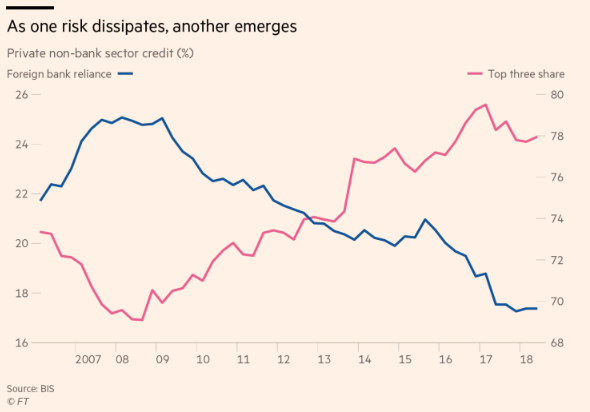

As a result, foreign bank reliance — the share of overall credit accounted for by foreign banks — has fallen from a peak of 28 per cent at the height of the financial crisis to 19 per cent, as depicted in the second chart.

Reliance on foreign bank lending has fallen markedly in Mexico, Poland and Argentina, as illustrated in the third chart, as well as in Russia where, from a peak of 27 per cent in 2007, it has dwindled to just 10 per cent.

Moreover, the composition of the remaining foreign bank credit has also, arguably, improved for the better. The BIS found that “international claims” — a measure of cross-border lending as well as local lending in foreign currency by locally funded subsidiaries of foreign banks — has declined in importance more than “local claims in local currency”, ie lending by these subsidiaries in domestic currency.

The latter are “usually funded locally and so may be more insulated from foreign developments”, said Mr Hardy. Borrowing in domestic currency can also help avoid potentially ruinous currency mismatches.

The decline in reliance on foreign bank lending has come at its own cost, however, with the remaining credit flows sourced from a narrower range of countries. The BIS found that concentration among foreign bank lenders — the share of foreign credit from the top three national banking systems, typically the US, UK and Japan, Spain or France — was falling in the run-up to the financial crisis.

However it has risen sharply since, as the fourth chart shows, something Mr Hardy feared made emerging economies more vulnerable to a banking crisis in one of these developed countries.

The level of concentration is particularly elevated in several Latin American nations, such as Chile, Colombia and Argentina, the BIS found. Banks from Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland have become less important in EMs since the financial crisis, with those from Australia, Canada, Japan and Spain supplanting them to some extent.

Mr Hardy’s country-by-country analysis suggested there was a clear link between the degree of reliance on foreign banks and the level of concentration of those banks.

“This strong negative correlation in the time series reveals much about the landscape of credit provision by foreign banks in emerging markets,” he said.

“Leading up to the GFC, banks from many foreign countries lent to emerging markets, contributing to an increase in the foreign bank reliance measure and a fall in concentration. After the crisis, domestic banks and non-bank creditors expanded into emerging market lending.

“Aggregate credit from foreign banks remained about the same, but the composition of lenders became more concentrated, as some creditors retreated from emerging market lending and others expanded.”

Mr Hardy believed this was an issue authorities in EM countries needed to keep on top of.

“The diversity of funding sources may be important for emerging markets to monitor. Diversifying funding sources can reduce the risk of sudden reversals of credit from foreign developments in a single creditor country,” he said. |