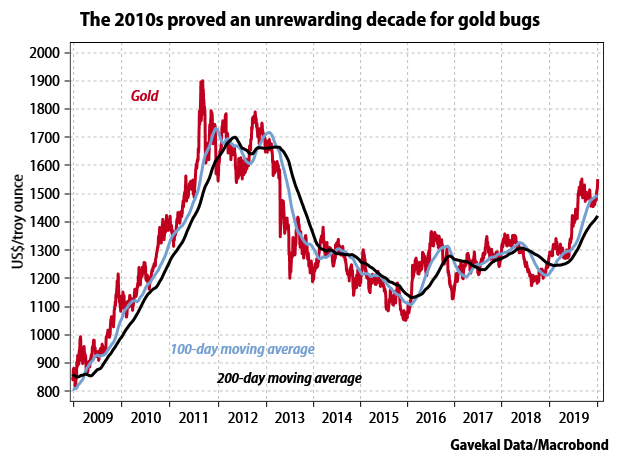

Gold: (report Jan 6, '20) has ripped higher in the last two days, climbing 3% since the killing on Friday of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani. But that price spike cannot compensate for the undeniable fact that the last 10 years have been a tough decade for the yellow metal. After a terrific 2011, the gold price mostly range-traded in 2012, collapsed in 2013, ground lower in 2014-15, then broadly range-traded again between 2016 and 2018.

In the spring and summer of 2019, gold did spring back to life, only to fade away in the fourth quarter. The latest geopolitical crisis in the Middle East has again jump-started gold’s price action, but that support may yet prove short-lived. So, what can we expect from gold going forward?

Interactive chart

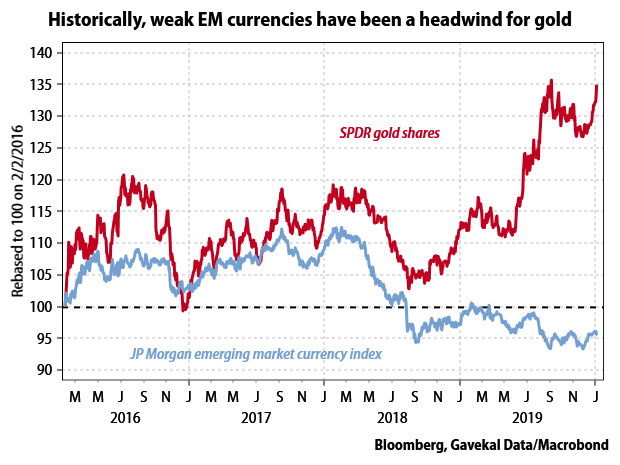

One long-held bias is that gold is just another (lower beta) way to play growth in emerging markets. After all, over recent decades most of the demand for physical gold has come from developing economies—mostly the Indian sub-continent, China, and the Middle East. So when emerging markets boom, gold tends to do well, and vice versa. Of course, fluctuations in the US dollar reinforce this relationship; a weak US dollar tends to be good for emerging markets, and also for gold (with the opposite equally true).

This may be the first—uncomfortable—explanation for the weakness of the gold price over the closing months of 2019. Even though the US Federal Reserve launched a new round of quantitative easing, emerging market currencies continued to make new lows, reflecting the aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus also taking place across the emerging world. And weak emerging market currencies are a genuine headwind for the gold price.

Interactive chart

In fact, perhaps the right question shouldn’t be why was gold so weak in the fourth quarter of 2019, but why it was so strong in the spring and summer while the broad emerging markets continued to struggle?

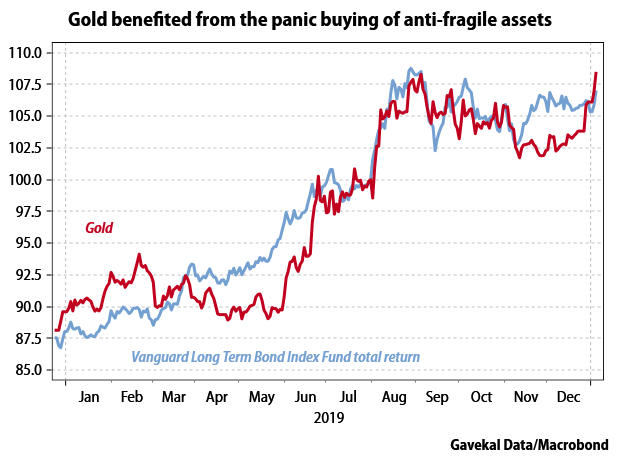

The answer is obvious enough: gold, like bonds and the Japanese yen, benefited from the panic-buying of “anti-fragile” assets (see The Surge in Anti-Fragile Assets and The End of the Panic).

And this panic buying was driven by:

1. Fears that Chinese tanks were set to roll down Connaught Road Central and that Hong Kong’s students would suffer the same fate as Beijing’s in 1989, which would have triggered an economic blockade of China and unleashed an unprecedented dislocation in global trade.

2. Fears that with Iran relaunching its nuclear program and challenging Saudi Arabia, the Middle East would soon be tearing itself apart.

Interactive chart

Fast forward to today and it is now fairly obvious that China has little interest in sending the People’s Liberation Army into Hong Kong. Instead, Hong Kong’s problems will continue to be handled by the city’s 31,000-strong police force. Meanwhile, the latest flare-up in US-Iran tensions notwithstanding, there is no advantage to the US administration in getting embroiled in a full-scale Middle Eastern conflagration, least of all in an election year (see A Dispassionate View Of The Iran Crisis). And while the Saudis may be willing, in the words of former US defense secretary Robert Gates, “to fight Iran to the last American,” without the US on point, Riyadh has no appetite at all for open conflict with its neighbor across the Gulf.

In addition, India’s fiscal and monetary stimulus may have encouraged Indian investors to reallocate savings away from gold and into domestic financial assets.

On top of that, the Aramco shakedown likely forced some prominent Saudi families to forego gold investment in order to buy their quotas of the rather unpopular IPO. Together these factors could help to explain the lackluster trajectory of gold in the last quarter of last year.

For let’s face it, beyond weak emerging market currencies, the end of the anti-fragile buying panic, and the likely reallocation of emerging market savings into other assets, gold really should have done better.

Consider the following:

· Seasonality. It is always tempting to push seasonality-related arguments a little too far. Still, when it comes to gold, a large part of the annual demand for the physical metal tends to occur in the period between Diwali (usually late October/early November) and Valentine’s day. This period encompasses Hanukkah, Christmas and Chinese New Year. So it was odd to see gold weaken meaningfully at a time when a large number of us were shopping around for jewelry for our significant others. Unless, that is, the softness in gold reflected generally weak retail sales over the holiday season—but the early indicators suggest no such weakness.

· Central banks are back to buying gold. In essence, over the past few decades, the market has had two consistent sellers of gold: gold miners, whose mission is to dig gold out of the ground and get it to the market, and central banks, who looked at their large gold reserves and bemoaned the fact that gold, unlike bonds, did not offer any yield. But that was then. Today, some US$12trn of bonds offer even lower yields than gold. Negative interest rates mean that for the first time ever, the “pet rock” looks attractive relative to bonds on a yield basis. As a result, a number of central banks would now rather own gold for the non-US-dollar component of their reserves than 10-year German bunds or 10-year Japanese government bonds. As central banks evolve from being marginal sellers of gold to become marginal buyers, the supply-demand dynamic should shift in support of the gold price—given that the only marginal sellers of gold in any meaningful size are now the gold miners.

· Gold miners are consolidating. Has there ever been a worse asset class than gold miners? The Philadelphia Stock Exchange gold and silver index (XAU Index on Bloomberg) stands at the same level today it did at the start of 1984 (that’s three and half decades of treading water). Meanwhile, since 2003 the MSCI World gold miners index has delivered annualized returns of 2%. Over the same 16 years, gold has returned 8.5% per annum.

Interactive chart

Perhaps unsurprisingly given this dismal performance, gold miners now find themselves starved of capital. This means the only path to growth left for them is industry consolidation and takeovers. Therefore, in the past few months, we have seen mergers between Newmont and Goldcorp, Barrick and Randgold, Pan American Silver and Tahoe, and Kirkland and Detour. To some extent, this is reminiscent of the mergers that took place in the energy sector at the end of the 20th century—BP-Amoco, Exxon-Mobil, Conoco-Philipps etc. It’s a textbook sign of a bottom in any given commodity’s cycle. When commodity extractors, who tend to be among the worst stewards of capital, would rather take out the competition and streamline costs than dig new holes in the ground, it tends to mean that future production is unlikely to soar. This should be supportive for gold prices.

If central banks are no longer selling gold, but are instead buying it, and if the number of gold miners continues to shrink by the week, while their inability to raise new capital suggests that new discoveries and the exploitation of large new mines are highly unlikely, then who will be the marginal seller of gold in the future? And at what price?

So, without going into the outlook for the US dollar at a time of active debt monetization by a central bank which has, for all intents and purposes, handed “the keys to the truck” to the US Treasury, and without going into the outlook for inflation at a time when the US median CPI already stands at 3%, it is possible to make a constructive argument for gold simply on future supply and demand.

As a result, it seems likely that the weakness towards the end of 2019 was nothing more than the counter-trend pullback following last summer’s panic buying of anti-fragile assets. With this in mind, even assuming the situations in Hong Kong and the Middle East deteriorate no further, it is possible to conclude that gold not only remains firmly supported—very likely at its 200-day moving average—but that it remains in a bull market. |