sounds about right

cannot be pleasant

I guess particularly jarring for those guilty before proven innocent

bloomberg.com

Ghislaine Maxwell Goes From Luxury Retreat to Turkish-Style Jail

Patricia Hurtado7 July 2020, 12:00 GMT+2

The Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, New York, on July 6.

Photographer: Johannes Eisele/AFP via Getty Images

LISTEN TO ARTICLE

Ghislaine Maxwell spent the last few months at a secluded 156-acre estate called “Tuckedaway,” hidden in the woods of Bradford, New Hampshire, -- the type of luxury retreat she’s grown accustomed to as Jeffrey Epstein’s girlfriend. Now, however, she’s having to deal with accommodations that have been compared to a Turkish prison.

Her new digs are at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, New York -- a dusty lockup adjacent to the waterfront and expressway in Sunset Park. It’s a place so notorious that a magistrate judge once said she was reluctant to send women there because of the “unconscionable” conditions.

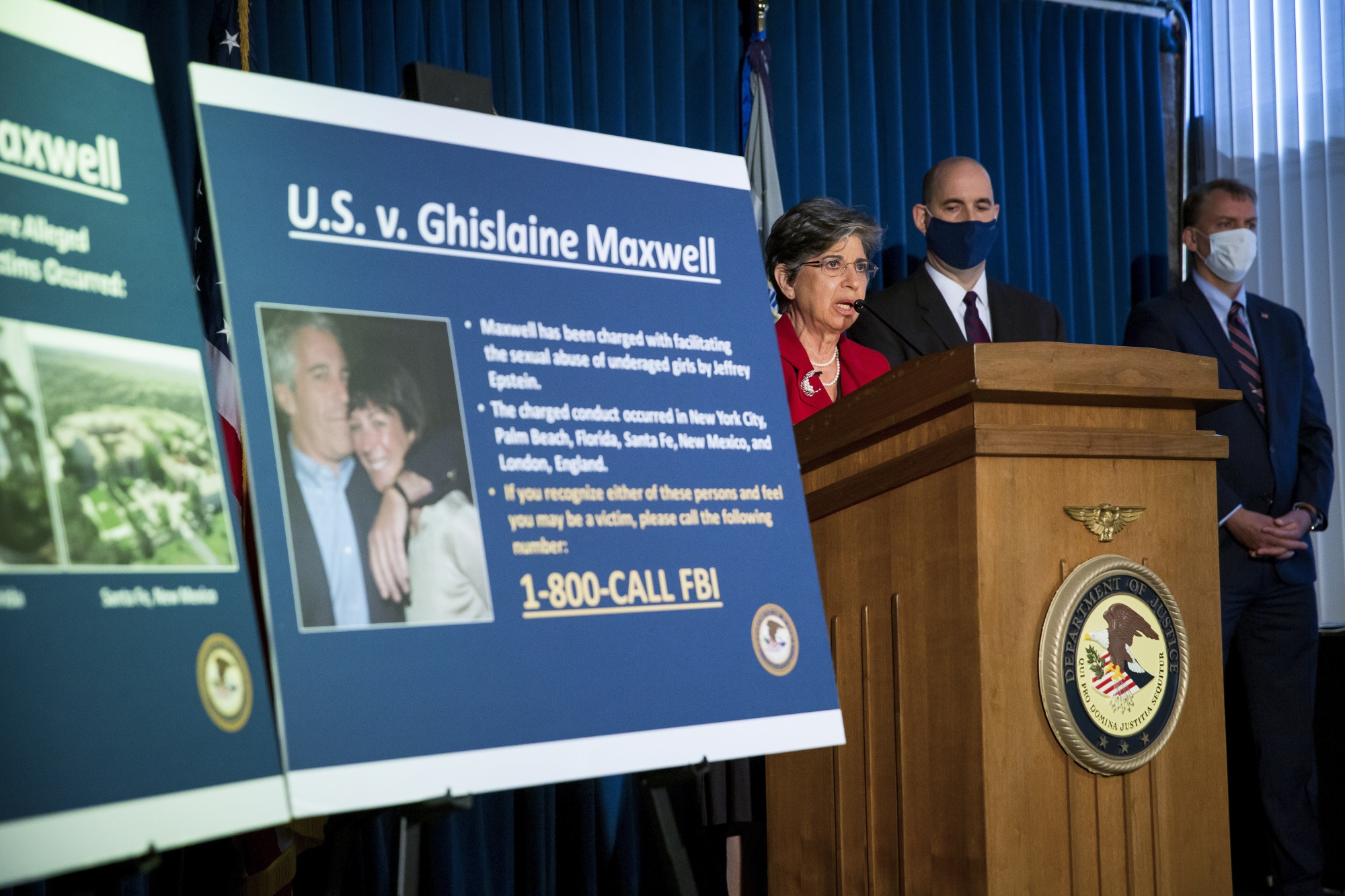

U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Audrey Strauss holds a news conference on July 2.

Photographer: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg

Maxwell, 58, has been in U.S. custody since her arrest Thursday in New Hampshire on multiple charges, including conspiracy to entice underage girls to engage in illegal sex acts with Epstein from 1994 through 1997. Epstein hung himself in a federal jail in Manhattan while awaiting trial on federal sex-trafficking charges.

Maxwell agreed to appear before a judge in Manhattan by videoconference from jail on July 14, when she is likely to be formally charged and enter a plea.

Photographer: Laura Cavanaugh/Getty Images

Since at least December, prosecutors say Maxwell has been “hiding out” in the sprawling four-bedroom and four-bath New Hampshire mansion which boasts cathedral ceilings, a barn and views of Mount Sunapee foothills from every room. The house was described by Sotheby’s as “an amazing retreat for the nature lover who also wants total privacy.”

But on Monday, U.S. Bureau of Prisons officials confirmed Maxwell was moved from a New Hampshire jail to the Metropolitan Detention Center, a federal jail that houses more than 1,600 male and female detainees. It’s part of a compound of massive shipping warehouses built at the turn of the century and used during both world wars.

No one wants to go to jail, but the conditions described at the MDC have been the subject of numerous complaints and scrutiny that rival the rat-infested federal lockup in Lower Manhattan where Epstein was held.

In early 2019, hundreds of inmates at the MDC were locked shivering in their cells for at least a week after an electrical fire knocked out power in the building. The inmates spent some of the coldest days of that winter in darkness, largely without heat and hot water.

Over the years, federal investigators have concluded the jail is among the worst in the U.S. Bureau of Prisons system, finding that prisoners have been beaten, raped or held in inhumane conditions. Two inmates died recently.

After the coronavirus hit New York, Homer Venters, a former chief medical officer for the city’s jails, visited the facility and concluded in a report that the facility was “ill-equipped” to deal with Covid-19 cases and failed to implement adequate infection-control practices.

Venters said he was “concerned about the ongoing health and safety of the population” at MDC, and condemned the failure of the jail’s officials to take simple steps to identify potentially sick patients and isolate them.

On LockdownIn a sworn statement filed April 28, Derrilyn Needham said she’d been incarcerated at the MDC since November 2019, along with 30 other women. They slept in bunk beds, and she said it was difficult to stay six feet apart. From April 20 to April 23, Needham said the women were on “lockdown on our bunk beds, not able to leave our bunks except to use the bathroom or shower.”

The inmates were allowed to make phone calls one day, Needham said, but they hadn’t been given gloves, hand sanitizer or disinfectant wipes. After suffering from symptoms she thought could be Covid-19, including chills, fever, extreme fatigue, cough and trouble breathing, she said the assistant warden told her she couldn’t be tested.

Voice mail and email messages to the U.S. Bureau of Prisons on Monday seeking comment about the MDC weren’t immediately returned.

Cheryl Pollak, the federal magistrate in Brooklyn, has repeatedly voiced concerns about the MDC after reviewing a report by the National Association of Women Judges, who visited the facility and found that 161 female inmates were housed 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in two large rooms that lacked windows, fresh air or sunlight and weren’t allowed out to exercise.

“Some of these conditions wouldn’t surprise me if we were dealing with a prison in Turkey or a Third World Country,” Pollak said during one 2016 hearing. “It’s hard for me to believe it’s going on in a federal prison.”

— With assistance by Clare Roth

Before it's here, it's on the Bloomberg Terminal.

LEARN MORE |