Re << Different approach from India which has continued to disappoint ..>>

The approach from India might be different, but likely the destination the same as India inevitably gives up any socialist ritual suicide tendencies and course-correct

Governments do not last as long when failing its people, we must believe. Success is better everything else being equal

Should a nation wish to grow a bit faster, go easier on its underground economy. Bitgold should prove helpful, for the people by the people and against no other people.

ft.com

The huge hidden economy is missing from and distorting our data

Unmeasured markets often respond first when times become tough and are a safety net when governments fail

March 11 2020

Bangkok: street vendors, hawkers, pop-ups and informal markets create jobs, spending, income and output, which should all be counted in GDP © Mladen Antonov/AFP/GettyThe writer is an economist and the author of ‘Extreme Economies’ Bangkok: street vendors, hawkers, pop-ups and informal markets create jobs, spending, income and output, which should all be counted in GDP © Mladen Antonov/AFP/GettyThe writer is an economist and the author of ‘Extreme Economies’

Getting economic policy right in turbulent times is fiendishly hard. Those controlling interest rates and taxes first need to understand the shock: is coronavirus a hit to demand, to supply, or both? Then they must predict human responses: how and when will consumers and businesses react?

Yet there is another difficulty, equally important, that few sitting in central banks or finance ministries contemplate: the problem of missing data. A vast unmeasured economy influences the markets we measure accurately. Typically seen as a poor-country problem, this missing economy looks very likely to grow over the coming decade. As it does, official economic data and the policies that result from it are likely to become worse.

The economy missing from our statistics is variously tagged as “underground”, “hidden”, “shadow” or “grey”. None of these labels are very helpful descriptors: much of what we fail to capture takes place at street level, is vibrant, colourful, self-regulated and well organised.

Some of it is illicit, but most simply exists outside taxation and government rules — the street vendors, hawkers, unregistered pop-up shops and informal markets that thrive around the world, for example. This kind of activity creates jobs, spending, income and output, which should all be counted in national gross domestic product but often goes unmeasured.

Recognising their failure, statistical agencies chip away at the problem. Some attack data gaps directly, comparing self-reported tax returns with the results of audits to gauge the extent to which sales might be hidden across an economy. Others use demand for currency and electricity as an indirect measure, reasoning that the need for power and cash should track the size of informal markets. The latest attempts use satellite images to track light emissions as a clue to the number of unreported factories and markets.

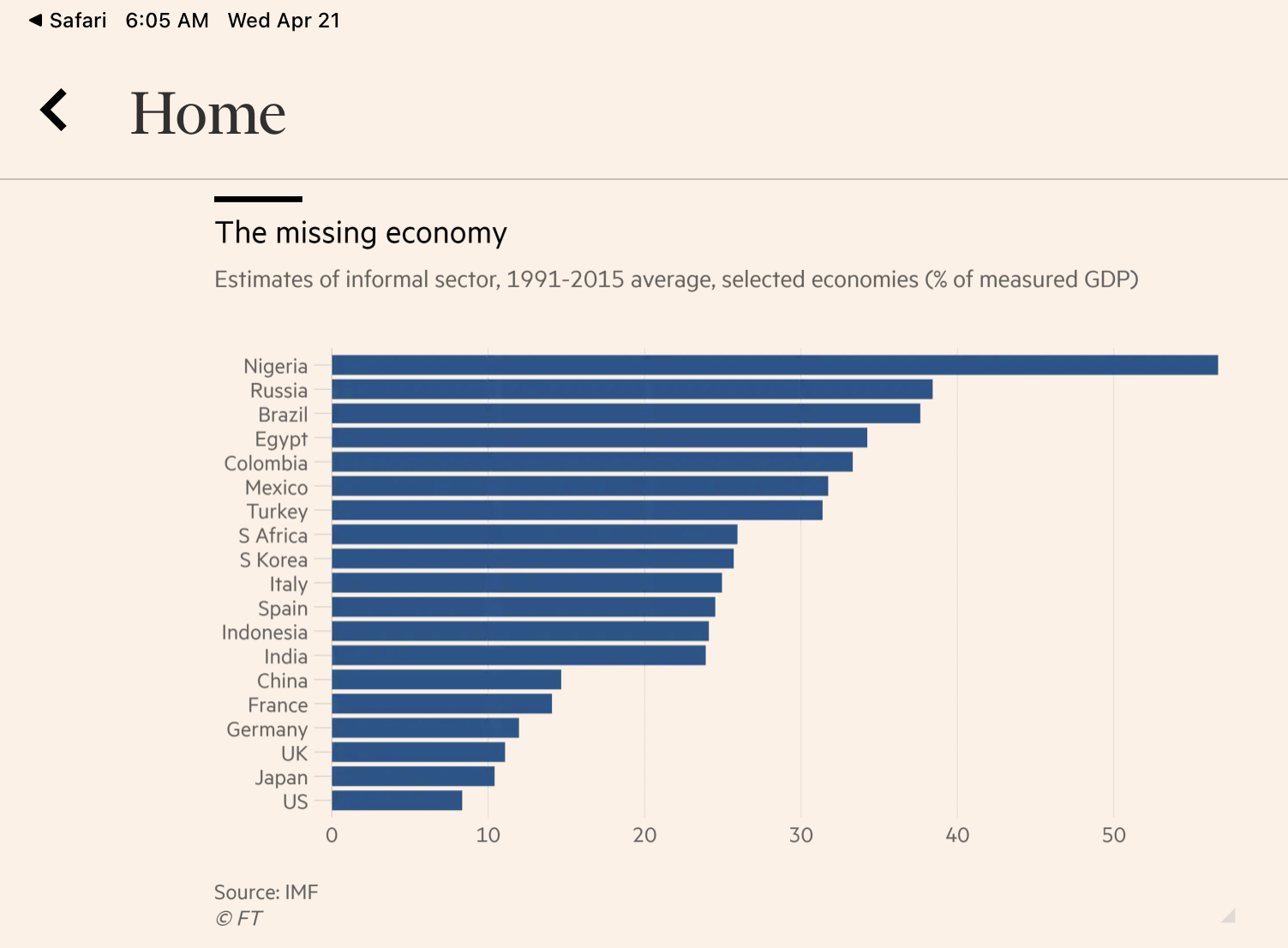

When figures on the unmeasured economy emerge, they are perplexing. It is massive: across 158 countries, the IMF recently put it at almost 32 per cent of measured GDP. In emerging and developing countries the share is higher. Recent work by local statisticians puts it at 52 per cent in India, for example.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo decent statistics are scant (the last census was in 1984) and the unmeasured economy may be 80 per cent of official GDP. Because all this unreported activity bypasses tax and can be unproductive, it is seen as a drain. The advice from bodies such as the IMF and the OECD is to tamp it down, fill the fiscal coffers and boost output.

Travelling in places where people live under acute stress has shown me how misplaced the mainstream view of informality can be. Refugee camps tend to have a handful of registered companies that international aid agencies deal with. Among these, thousands of pop-up shops jostle to provide a choice of goods and jobs to people under duress.

Kinshasa is the same story on a much larger scale: a sprawling mega-village of 10m people, the vast majority working informally. During recent protests in Santiago, an informal market sprang up to provide essentials including water, food and nappies. Unmeasured markets often respond first when times become tough and are a safety net when governments fail.

The rich world has much to do before dishing out advice. Italy, a G7 member, misses one-quarter of its economy, according to IMF estimates. Only Austria, Switzerland and the US measure well enough that the missing economy is below 10 per cent of GDP.

Things could get worse. The over-65s often pick up informal jobs when they retire. As this cohort swells, the unmeasured economy will rise. Technology, too, is a challenge: the sharing economy — outfits including Airbnb — is proving hard to track. Online networks make informal trade easier: a social economy of unregistered takeaways, markets and lending clubs conducted through Facebook is rising.

Unless statisticians catch up, the result will be bad policy. If measures of GDP miss the true picture, then the rules on debt-to-GDP ratios are going to be wrong, too. If informal groups are a source of innovation — an idea that many studies bear out — then tax breaks and subsidies directed at small and medium-sized enterprises need rerouting in their direction.

If the unmeasured economy is large enough to affect business cycles, as US Federal Reserve economists have shown, then interest-rate rises and cuts could be mistimed. Accurate policy rests on having access to a full picture of the way people work, earn and spend. Until we have one, economics can only bump along blindly.

Sent from my iPad |