As World Runs Short of Workers, a Boost for Wages—and Inflation

In the two largest economies, plunging birthrates and aging populations squeeze the labor supply

By Greg Ip

May 12, 2021 9:04 am ET

View article to see the charts.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/as-world-runs-short-of-workers-a-boost-for-wagesand-inflation-11620824675?mod=e2tw

The inflationary pressures now roiling the economy and markets will probably fade once the economy has fully reopened and the pandemic is in remission.

Yet beneath the surface some of the forces that have long kept inflation in check are starting to turn. Most important: demographics.

The world’s two largest economies have just reported that their population growth in the past decade was the slowest in generations, as people aged and birthrates plummeted.

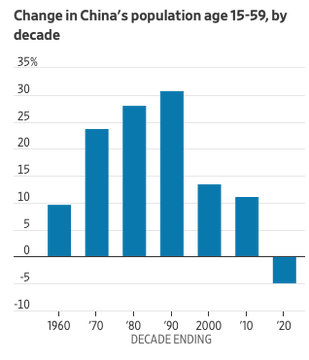

Change in China's population age 15-59, bydecadeSource: United Nations (1970-2000); China NationalBureau of Statistics (2010-20)

Lower fertility initially boosts the labor supply by enabling more women to enter the workforce. But fertility has been falling for so long in the U.S. and China that those demographic dividends were spent long ago, and now they face the consequences: a diminished supply of workers.

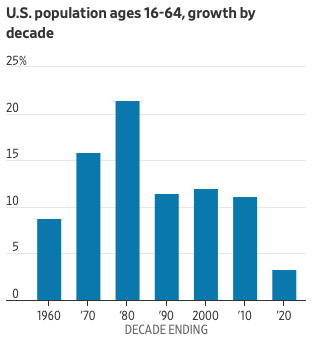

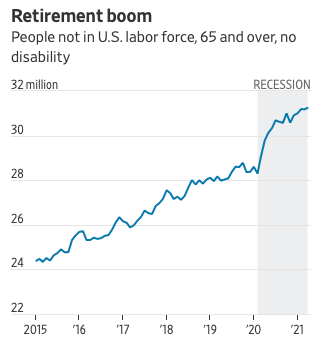

The U.S. population grew 7% between 2010 and 2020, the slowest since the 1930s, according to decennial census results released last month. The age breakdown isn’t yet available, but a smaller sample by the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the working-age population—those ages 16 to 64—grew just 3.3%. Because the share of those people working or looking for work has shrunk, the working-age labor force grew only 2%, and actually shrank last year. Some of those missing workers will return when the virus recedes, schools reopen and unemployment insurance becomes less generous. But many won’t: Baby boomer retirements have soared.

Reversing this move would require either a dramatic increase in births, which has eluded countries with more-family-friendly policies (and the labor force wouldn’t benefit for years), or immigration, which is politically hard.

The demographic squeeze is far more severe in China, which unlike the U.S. admits almost no immigrants and for years limited families to one child. On Tuesday, authorities announced that the population in China had grown just 5.4% in the past decade. The working-age population—those ages 15 to 59—shrank 5%, or roughly 45 million people. When worker shortages began emerging over a decade ago, factories began moving to poorer inland provinces and then cheaper countries including Vietnam. In recent years some indicators suggest jobs are getting harder to fill, though the data might not be nationally representative.

Workers produce more than they consume while dependents—children and retirees—consume more than they produce, economists Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan argue in their book “The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival,” published last year. Over the past three decades the integration of China and Eastern Europe into the global economy, the entry of baby boomers into the workforce and rising women’s participation effectively doubled the labor supply of advanced economies, putting downward pressure on costs and workers’ bargaining power.

That move is now reversing as dependents grow much more quickly than workers, and “dependents are inflationary,” Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan write. A growing share of a shrinking labor force must be devoted to supporting the elderly: “Think of the one child policy in China, with one grandchild to four grandparents, two of whom could easily contract dementia.”

Aging creates numerous problems for economies long used to plentiful labor and low inflation. The elderly’s political clout makes it hard, even for authoritarian societies such as Russia, to raise the retirement age or trim pensions. Then-President Donald Trump broke with Republican orthodoxy by opposing reduced benefits for Social Security or Medicare. President Biden has proposed lowering the Medicare retirement age to 60 from 65 and pouring more money into elder care. Such a move enhances quality of life, but it also adds to cost pressures because healthcare is notoriously resistant to labor-saving efficiency.

Workers nearing retirement are in their highest-saving years. As they retire, they draw down those savings. Young adults are marrying later, leaving fewer years to save. Corporations might have to invest more to compensate for shrinking workforces. All of this will chip away at the “global saving glut” that has held interest rates down in recent decades, Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan argue.

Whether inflation actually accelerates is largely up to central banks. But shifting demographics could change their challenge, from fighting to keep inflation up in the face of deflationary forces, to keeping it down in the midst of inflationary forces.

Of course, numerous other factors are at work. Indeed, the world, in particular Japan, has been aging for a while without any obvious effect on inflation and interest rates. Some studies have found that low-wage competition from China did hold down U.S. inflation, but outsourcing had basically peaked by the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Even the steep tariffs that the U.S. imposed on Chinese imports in 2018 and 2019 didn’t raise prices much.

One reason might be that private investment sank in the aftermath of the financial crisis, which was only partially offset by government borrowing. By contrast, investment has remained steady throughout the pandemic, and government borrowing has soared. As for Japan, Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan argue that it began running out of workers when it could still outsource production to China. That is no longer an option.

At The Wall Street Journal's CEO Council Summit, Janet Yellen expressed her confidence that the U.S. economy and employment will return to normal by next year.

China itself doesn’t plan to let aging change its high-saving, high-investment model, notes Andrew Batson of Gavekal Dragonomics, a research service. A recent paper by the People’s Bank of China acknowledges the demographic challenge but argued against letting saving and investment decline as a result: “Consumption is never a source of growth.…The high consumption rate of developed economies has historical reasons; once you switch, there’s no going back, so we should not take them as an example to learn from.”

Yet what matters for the world is whether Chinese saving and investment depress global inflation and interest rates. China is directing more of its investment inward while facing rising barriers to its exports as Western voters sour on globalization and China.

After decades of declining power, “labor has retaliated, not at the wage bargaining table, but in the voting booth,” write Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan, adding that globalization “has been checked by populism, just at the time that demographic factors are swinging back to labor’s advantage.” |