Merkel’s caution has made Germany the great economic underachiever of our times

September 23, 2021 4.00pm SAST

Author

Muhammad Ali Nasir

Associate Professor in Economics and Finance, University of Huddersfield

Disclosure statementMuhammad Ali Nasir does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Huddersfield provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

The Conversation is funded by the National Research Foundation, eight universities, including the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Rhodes University, Stellenbosch University and the Universities of Cape Town, Johannesburg, Kwa-Zulu Natal, Pretoria, and South Africa. It is hosted by the Universities of the Witwatersrand and Western Cape, the African Population and Health Research Centre and the Nigerian Academy of Science. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a Strategic Partner. more

Germans are taking to the polls on September 26 to elect the members for the 20th Bundestag. For the first time in 16 years, there will be a new chancellor as Angela Merkel steps down. Germany has been through some enormous challenges during her tenure, including the global financial crisis, European sovereign debt crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, and many commentators have praised her quiet efficiency.

The polls are predicting gains for the Social Democrats (SPD), who have been the junior coalition partner to Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) since 2013, but no party is expected to achieve a landslide victory. The SPD’s Olaf Scholz is the most likely successor to Merkel. He is already finance minister and vice chancellor in the outgoing administration, so the German political landscape looks unlikely to change drastically.

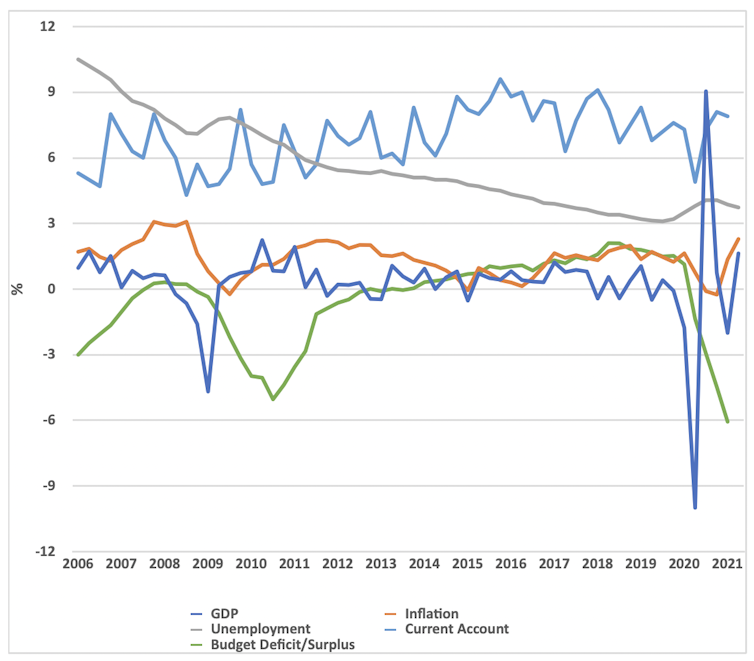

Yet the Germans would arguably benefit from changing their approach to running the economy, because it has not fared brilliantly under Merkel – and this would apply regardless of how the election turns out. The chart below, which shows what has happened to key indicators like growth, inflation and unemployment during her tenure, shows a very mixed picture.

Germany’s economy under Merkel

Notes: current account and budget surplus/deficit are both as % of GDP; unemployment is a % of working population; GDP growth and inflation are quarter on quarter; inflation is consumer price index. OECD, ECB, BundesbankOn the one hand, the fact that prices have been so static and most people have been in work are signs of a well run economy. Yet GDP growth has been quite low – and surely lower than it could have been given that Germany has been running large trade surpluses and also either surpluses in the public finances or small deficits. In other words, Germany could have spent more to encourage consumption and investment.

But Germany is famous for its determination to always balance its books. Under Merkel (and previous chancellors) the nation locked itself into a fiscal straitjacket variously known as schuldenbremse (“the debt brake”), schwarze null (“black zero”) or the balanced budget rule. It all boils down to German federal and state governments not being allowed to run budget deficits.

At the same time, German households are the thriftiest in the G7, boasting the highest savings rate. German household spending has consistently declined, from 56.4% as a percentage of their disposable income in 2009 to 51.9% in 2019, and obviously, COVID-19 dragged it further down to 50.7% in 2020.

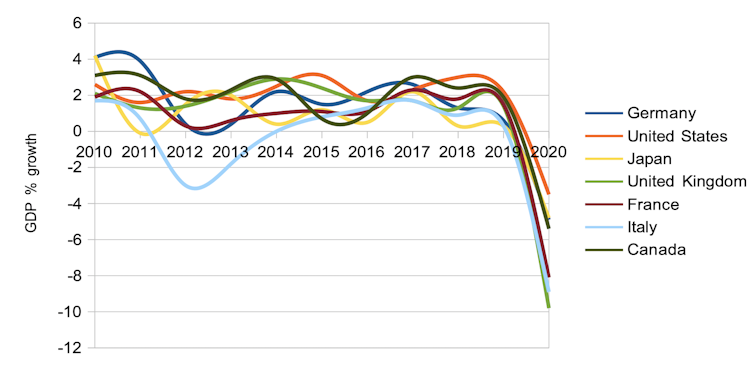

GDP growth across G7, 2010-20

World Bank

Both public and private fixed investment in Germany has been declining for decades as a percentage of GDP, despite all the money generated by the huge trade surplus. Lack of investment has started to weigh on the German economy, as manifested in the poor growth numbers.

Germany was showing 0% growth in the final quarter of 2019 even before the COVID-19 nosedive. So despite Germany’s fiscal prudence and gigantic trade surplus, the period between the global financial crisis and COVID-19 cannot be seen as a success story. It has been a period of long-term stagnation.

The pandemic era

In the era before the pandemic, Germany’s large trade surplus was causing international ructions, with the US branding the Germans currency manipulators. Yet neither the surplus nor the stagnation vanished under Merkel. As usual, Germany’s fascination with fiscal prudence came out on top.

Germany’s great strength in exports has been somewhat immune to COVID. The country’s trade balance did deteriorate a bit in 2020 as international demand for German goods was affected by the pandemic.

But now that its major trading partners have lifted the worst of their COVID restrictions, German exports have bounced back to levels last seen three years ago, with a trade surplus of €110 billion (£95 billion) in the first half of 2021. This confirms that the competitiveness of the German economy is the last thing anyone needs to worry about.

Germany did put its fiscal prudence on hold to deal with the pandemic, condoning a budget deficit of around 6% in its efforts to support citizens and businesses. In parallel, German households have drawn down on their savings during the pandemic, though only marginally.

The saving rate dropped from 10% of GDP in 2019 to 7.7% of GDP in 2020. But knowing German fiscal conservatism at both the national and household levels, business as usual is likely to be resumed shortly.

The future

The two most pressing issues for the new chancellor are be economic recovery from COVID and reaching net zero carbon emissions. Earlier this year, Merkel raised Germany’s targeted date for reaching net zero from 2050 to 2045 after the German constitutional court found that the government was violating the freedoms of young people by delaying too much of its emissions reduction until after 2030. When the nation was hit by terrible floods in the summer, it highlighted both the urgency of responding to climate change and also the public appetite for urgent action.

Yet maintaining prosperity while making such huge cuts to carbon emissions is going to be a monumental challenge, not always made easier by other political decisions: for example, part of Germany’s climate plan involves phasing out coal power by 2038, but this is complicated by also phasing out nuclear power by 2022.

In sum, the new chancellor will have to maintain a very tight balance between these environmental ambitions and economic recovery and growth after COVID. Another major issue that will only make this harder is Germany’s ageing population.

Merkel has lately been coming under pressure to raise the state pension age to 68, having already raised it from 65 to 67 from 2029. But she has left the decision to her successor, and Scholz has ruled out such a move, insisting it is unnecessary.

One obvious priority should be to revisit the nation’s addiction to stagnation-inducing surpluses. By moving away from schwarze null to run deficits closer to the 3% permitted under the EU Stability and Growth Pact, the new chancellor could create a little more space to make COVID recovery and the environmental transition easier. After the cautious Merkel years, the time is ripe for the Germans to try something different. |