So far as any where that has bragged about beating covid 19 was soon was back in a surge.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

NEWS FEATURE21 October 2020

The false promise of herd immunity for COVID-19

Why proposals to largely let the virus run its course — embraced by Donald Trump’s administration and others — could bring “untold death and suffering”.

Christie Aschwanden

Twitter Facebook Email

A New Jersey campaign rally for US President Donald Trump, who has espoused herd immunity as a strategy to deal with the pandemic.Credit: Spencer Platt/Getty A New Jersey campaign rally for US President Donald Trump, who has espoused herd immunity as a strategy to deal with the pandemic.Credit: Spencer Platt/Getty

In May, the Brazilian city of Manaus was devastated by a large outbreak of COVID-19. Hospitals were overwhelmed and the city was digging new grave sites in the surrounding forest. But by August, something had shifted. Despite relaxing social-distancing requirements in early June, the city of 2 million people had reduced its number of excess deaths from around 120 per day to nearly zero.

In September, two groups of researchers posted preprints suggesting that Manaus’s late-summer slowdown in COVID-19 cases had happened, at least in part, because a large proportion of the community’s population had already been exposed to the virus and was now immune. Immunologist Ester Sabino at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, and her colleagues tested more than 6,000 samples from blood banks in Manaus for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2.

“We show that the number of people who got infected was really high — reaching 66% by the end of the first wave,” Sabino says. Her group concluded 1 that this large infection rate meant that the number of people who were still vulnerable to the virus was too small to sustain new outbreaks — a phenomenon called herd immunity. Another group in Brazil reached similar conclusions 2.

Such reports from Manaus, together with comparable arguments about parts of Italy that were hit hard early in the pandemic, helped to embolden proposals to chase herd immunity. The plans suggested letting most of society return to normal, while taking some steps to protect those who are most at risk of severe disease. That would essentially allow the coronavirus to run its course, proponents said.

Rethinking herd immunity Rethinking herd immunity

But epidemiologists have repeatedly smacked down such ideas. “Surrendering to the virus” is not a defensible plan, says Kristian Andersen, an immunologist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. Such an approach would lead to a catastrophic loss of human lives without necessarily speeding up society’s return to normal, he says. “We have never successfully been able to do it before, and it will lead to unacceptable and unnecessary untold human death and suffering.”

Despite widespread critique, the idea keeps popping up among politicians and policymakers in numerous countries, including Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. US President Donald Trump spoke positively about it in September, using the malapropism “herd mentality”. And even a few scientists have pushed the agenda. In early October, a libertarian think tank and a small group of scientists released a document called the Great Barrington Declaration. In it, they call for a return to normal life for people at lower risk of severe COVID-19, to allow SARS-CoV-2 to spread to a sufficient level to give herd immunity. People at high risk, such as elderly people, it says, could be protected through measures that are largely unspecified. The writers of the declaration received an audience in the White House, and sparked a counter memorandum from another group of scientists in The Lancet, which called the herd-immunity approach a “dangerous fallacy unsupported by scientific evidence” 3.

Arguments in favour of allowing the virus to run its course largely unchecked share a misunderstanding about what herd immunity is, and how best to achieve it. Here, Nature answers five questions about the controversial idea.

What is herd immunity?Herd immunity happens when a virus can’t spread because it keeps encountering people who are protected against infection. Once a sufficient proportion of the population is no longer susceptible, any new outbreak peters out. “You don’t need everyone in the population to be immune — you just need enough people to be immune,” says Caroline Buckee, an epidemiologist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

Typically, herd immunity is discussed as a desirable result of wide-scale vaccination programmes. High levels of vaccination-induced immunity in the population benefits those who can’t receive or sufficiently respond to a vaccine, such as people with compromised immune systems. Many medical professionals hate the term herd immunity, and prefer to call it “herd protection”, Buckee says. That’s because the phenomenon doesn’t actually confer immunity to the virus itself — it only reduces the risk that vulnerable people will come into contact with the pathogen.

But public-health experts don’t usually talk about herd immunity as a tool in the absence of vaccines. “I’m a bit puzzled that it’s now used to mean how many people need to get infected before this thing stops,” says Marcel Salathé, an epidemiologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne.

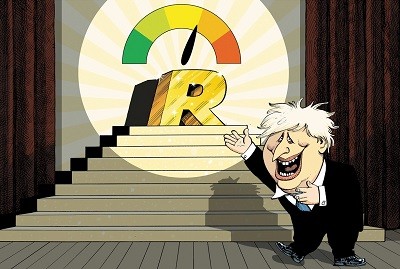

How do you achieve it?Epidemiologists can estimate the proportion of a population that needs to be immune before herd immunity kicks in. This threshold depends on the basic reproduction number, R0 — the number of cases, on average, spawned by one infected individual in an otherwise fully susceptible, well-mixed population, says Kin On Kwok, an infectious-disease epidemiologist and mathematical modeller at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The formula for calculating the herd-immunity threshold is 1–1/R0 — meaning that the more people who become infected by each individual who has the virus, the higher the proportion of the population that needs to be immune to reach herd immunity. For instance, measles is extremely infectious, with an R0 typically between 12 and 18, which works out to a herd-immunity threshold of 92–94% of the population. For a virus that is less infectious (with a lower reproduction number), the threshold would be lower. The R0 assumes that everyone is susceptible to the virus, but that changes as the epidemic proceeds, because some people become infected and gain immunity. For that reason, a variation of R0 called the R effective (abbreviated Rt or Re) is sometimes used in these calculations, because it takes into consideration changes in susceptibility in the population.

A guide to R — the pandemic’s misunderstood metric A guide to R — the pandemic’s misunderstood metric

Although plugging numbers into the formula spits out a theoretical number for herd immunity, in reality, it isn’t achieved at an exact point. Instead, it’s better to think of it as a gradient, says Gypsyamber D’Souza, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. And because variables can change, including R0 and the number of people susceptible to a virus, herd immunity is not a steady state.

Even once herd immunity is attained across a population, it’s still possible to have large outbreaks, such as in areas where vaccination rates are low. “We’ve seen that play out in certain countries where misinformation about vaccine safety has spread,” Salathé says. “In local pockets, you start to see a drop in vaccinations, and then you can have local outbreaks which can be very large, even though you’ve technically reached herd immunity as per the math.” The ultimate goal is to prevent people from becoming unwell, rather than to attain a number in a model.

How high is the threshold for SARS-CoV-2?Reaching herd immunity depends in part on what’s happening in the population. Calculations of the threshold are very sensitive to the values of R, Kwok says. In June, he and his colleagues published a letter to the editor in the Journal of Infection that demonstrates this 4. Kwok and his team estimated the Rt in more than 30 countries, using data on the daily number of new COVID-19 cases from March. They then used these values to calculate a threshold for herd immunity in each country’s population. The numbers ranged from as high as 85% in Bahrain, with its then-Rt of 6.64, to as low as 5.66% in Kuwait, where the Rt was 1.06. Kuwait’s low numbers reflected the fact that it was putting in place lots of measures to control the virus, such as establishing local curfews and banning commercial flights from many countries. If the country stopped those measures, Kwok says, the herd-immunity threshold would go up.

A cemetery in Manaus, Brazil, in June. The city was hit hard by an outbreak of coronavirus in April and May, and cases there are now rising again.Credit: Michael Dantas/AFP via Getty A cemetery in Manaus, Brazil, in June. The city was hit hard by an outbreak of coronavirus in April and May, and cases there are now rising again.Credit: Michael Dantas/AFP via Getty

Herd-immunity calculations such as the ones in Kwok’s example are built on assumptions that might not reflect real life, says Samuel Scarpino, a network scientist who studies infectious disease at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. “Most of the herd-immunity calculations don’t have anything to say about behaviour at all. They assume there’s no interventions, no behavioural changes or anything like that,” he says. This means that if a transient change in people’s behaviour (such as physical distancing) drives the Rt down, then “as soon as that behaviour goes back to normal, the herd-immunity threshold will change.”

Estimates of the threshold for SARS-CoV-2 range from 10% to 70% or even more 5, 6. But models that calculate numbers at the lower end of that range rely on assumptions about how people interact in social networks that might not hold true, Scarpino says. Low-end estimates imagine that people with many contacts will get infected first, and that because they have a large number of contacts, they will spread the virus to more people. As these ‘superspreaders’ gain immunity to the virus, the transmission chains among those who are still susceptible are greatly reduced. And “as a result of that, you very quickly get to the herd-immunity threshold”, Scarpino says. But if it turns out that anybody could become a superspreader, then “those assumptions that people are relying on to get the estimates down to around 20% or 30% are just not accurate”, Scarpino explains. The result is that the herd-immunity threshold will be closer to 60–70%, which is what most models show (see, for example, ref. 6).

Looking at known superspreader events in prisons and on cruise ships, it seems clear that COVID-19 spreads widely initially, before slowing down in a captive, unvaccinated population, Andersen says. At San Quentin State Prison in California, more than 60% of the population was ultimately infected before the outbreak was halted, so it wasn’t as if it magically stopped after 30% of people got the virus, Andersen says. “There’s no mysterious dark matter that protects people,” he says.

And although scientists can estimate herd-immunity thresholds, they won’t know the actual numbers in real time, says Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. Instead, herd immunity is something that can be observed with certainty only by analysing the data in retrospect, maybe as long as ten years afterwards, she says.

Will herd immunity work?Many researchers say pursuing herd immunity is a bad idea. “Attempting to reach herd immunity via targeted infections is simply ludicrous,” Andersen says. “In the US, probably one to two million people would die.”

California’s San Quentin prison declined free coronavirus tests and urgent advice — now it has a massive outbreak California’s San Quentin prison declined free coronavirus tests and urgent advice — now it has a massive outbreak

In Manaus, mortality rates during the first week of May soared to four-and-a-half times what they had been the preceding year 7. And despite the subsequent excitement over the August slowdown in cases, numbers seem to be rising again. This surge shows that speculation that the population in Manaus has reached herd immunity “just isn’t true”, Andersen says.

Deaths are only one part of the equation. Individuals who become ill with the disease can experience serious medical and financial consequences, and many people who have recovered from the virus report lingering health effects. More than 58,000 people were infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Manaus, so that translates to a lot of human suffering.

Earlier in the pandemic, media reports claimed that Sweden was pursuing a herd immunity strategy by essentially letting people live their lives as normal, but that idea is a “misunderstanding”, according to the country’s minister for health and social affairs, Lena Hallengren. Herd immunity “is a potential consequence of how the spread of the virus develops, in Sweden or in any other country”, she told Nature in a written statement, but it is “not a part of our strategy”. Sweden’s approach, she said, uses similar tools to most other countries: “Promoting social distancing, protecting vulnerable people, carrying out testing and contact tracing, and reinforcing our health system to cope with the pandemic.” Despite this, Sweden is hardly a model of success — statistics from Johns Hopkins University show the country has seen more than ten times the number of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 people seen in neighbouring Norway (58.12 per 100,000, compared with 5.23 per 100,000 in Norway). Sweden’s case fatality rate, which is based on the number of known infections, is also at least three times those of Norway and nearby Denmark.

What else stands in the way of herd immunity?The concept of achieving herd immunity through community spread of a pathogen rests on the unproven assumption that people who survive an infection will become immune. For SARS-CoV-2, some kind of functional immunity seems to follow infection, but “to understand the duration and effects of the immune response we have to follow people longitudinally, and it’s still early days”, Buckee says.

COVID-vaccine results are on the way — and scientists’ concerns are growing COVID-vaccine results are on the way — and scientists’ concerns are growing

Nor is there yet a foolproof way to measure immunity to the virus, Rivers says. Researchers can test whether people have antibodies that are specific to SARS-CoV-2, but they still don’t know how long any immunity might last. Seasonal coronaviruses that cause common colds provoke a waning immunity that seems to last approximately a year, Buckee says. “It seems reasonable as a hypothesis to assume this one will be similar.”

In recent months, there have been reports of people being reinfected with SARS-CoV-2 after an initial infection, but how frequently these reinfections happen and whether they result in less serious illnesses remain open questions, says Andersen. “If the people who are infected become susceptible again in a year, then basically you’ll never reach herd immunity” through natural transmission, Rivers says.

“There’s no magic wand we can use here,” Andersen says. “We have to face reality — never before have we reached herd immunity via natural infection with a novel virus, and SARS-CoV-2 is unfortunately no different.” Vaccination is the only ethical path to herd immunity, he says. How many people will need to be vaccinated — and how often — will depend on many factors, including how effective the vaccine is and how long its protection lasts.

People are understandably tired and frustrated with imposed measures such as social distancing and shutdowns to control the spread of COVID-19, but until there is a vaccine, these are some of the best tools around. “It is not inevitable that we all have to get this infection,” D’Souza says. “There are a lot of reasons to be very hopeful. If we can continue risk-mitigation approaches until we have an effective vaccine, we can absolutely save lives.”

Nature 587, 26-28 (2020)

doi: doi.org

References

1.Buss, L. F. et al. Preprint at medRxiv doi.org (2020).

2.Prowse, T. A. A. et al. Preprint at medRxiv doi.org (2020).

3.Alwan, N. A. et al. Lancet doi.org (2020).

Article Google Scholar

4.Kwok, K. O. et al. J. Infect. 80, e32–e33 (2020).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

5.Aguas, R. et al. Preprint at medRxiv doi.org (2020).

6.Gomes, M. G. M. et al. Preprint at medRxiv doi.org (2020).

7.Orellana, J. D. Y., da Cunha, G. M., Marrero, L., Horta, B. L. & Leite, I. da C. Cad. Saúde Pública 36, e00120020 (2020).

PubMed Article Google Scholar |