Something about common prosperity :0)))

bloomberg.com

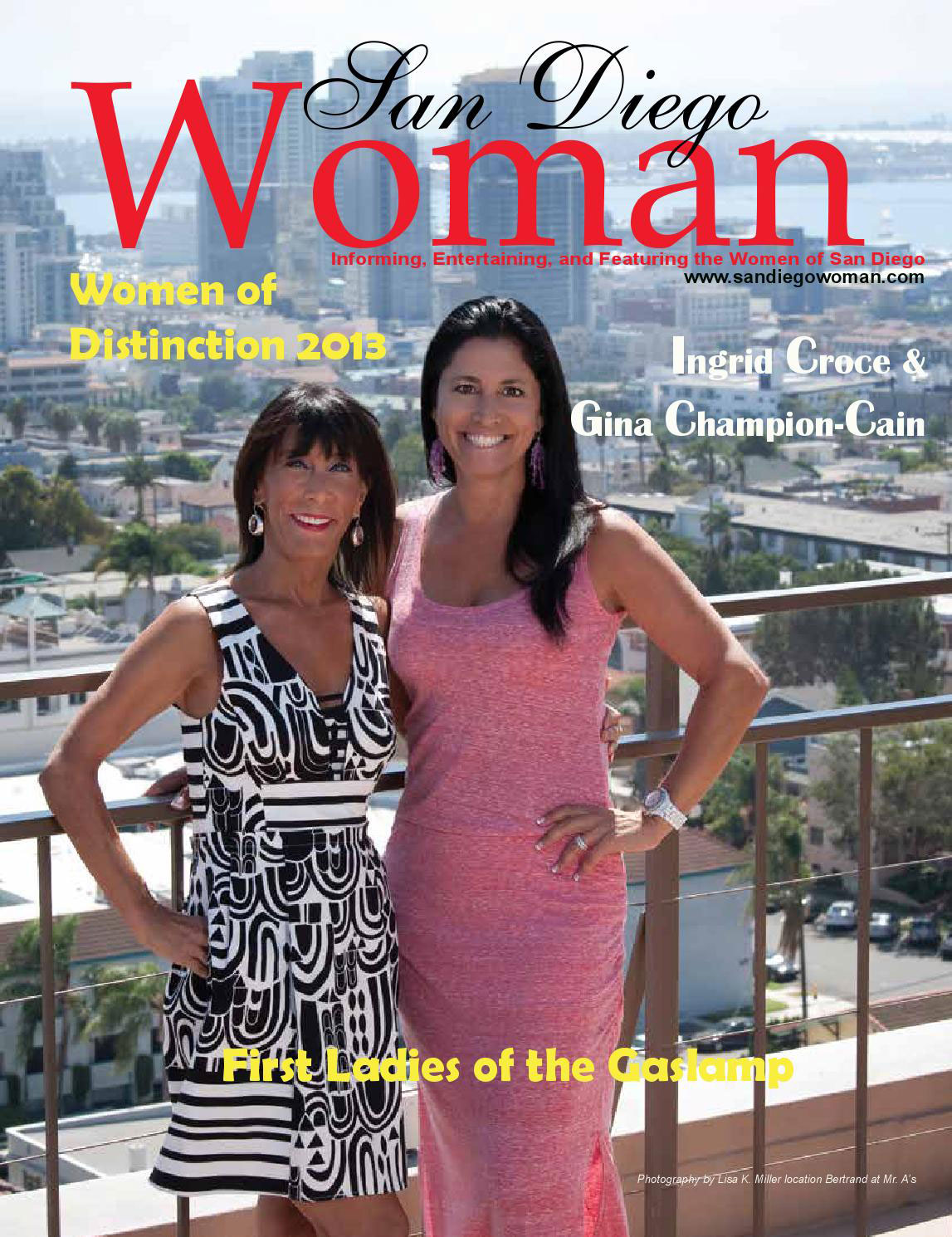

The Charismatic Developer and the Ponzi Scheme That Suckered San Diego

Gina Champion-Cain was a pillar of the local business community. But her successful image and lavish lifestyle were fueled by a fraud.

Chris Pomorski

January 21, 2022, 7:00 PM GMT+8

Champion-Cain

Photo illustration: 731: Photographer: Eduardo Contreras/San Diego Union-Tribune/Zuma Press

In late 2012, Kim Peterson, a San Diego real estate developer and lawyer, got a call from a friend and colleague named Gina Champion-Cain. Peterson was in his 60s; in 1982 he left behind a high-profile criminal defense practice in Chicago to build shopping centers, pharmacies, and luxury homes. With his wife, Laurie, he lived in a stylish Mediterranean villa with views of the Pacific and traveled on his own plane. In business circles, Peterson was known for probity and sound judgment. Through mutual acquaintances, he’d met Champion-Cain, roughly 15 years his junior, around 2005. They became close, playing golf at the exclusive Rancho Santa Fe country club where they were members and dining together with their spouses. Now she had an investment opportunity to tell him about.

Champion-Cain owned a real estate company, American National Investments Inc., and had recently bought her first restaurant. She was learning about liquor license regulations. When a license is transferred from one owner to another, she told Peterson, California law requires that the buyer and seller apply for approval to the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control. Within 30 days of applying, the parties are obliged to open an escrow account, into which the buyer must deposit the purchase price of the license. California liquor licenses can be more than $100,000. Many buyers, Champion-Cain said, are caught off guard by quickly having to come up with so much cash. She told Peterson that she’d recently met with a liquor license attorney who wished that his clients could get financing to cover their deposits while they waited for approval.

Here was the opportunity. By collecting money from investors, including wealthy acquaintances and friends, Champion-Cain had created a fund to provide short-term, high-interest loans to liquor license applicants. When, upon approval of a transfer, the buyer provided the cash for the purchase and the escrow closed, the loan principal and interest flowed back to the fund. Returns varied depending on a loan’s duration but could hit 25%. The liquor license attorney, Champion-Cain said, had a steady supply of worthy applicants, and Chicago Title, one of the largest title insurance providers in the U.S., was overseeing the escrow accounts. (Chicago Title has headquarters in Los Angeles and Jacksonville, Fla.)

Champion-Cain got a lot of attention in the local press for her entrepreneurial endeavors.

Photographer: John Gastaldo/San Diego Union-Tribune/Zuma Press

To Peterson, it sounded as though his friend had identified an overlooked, potentially lucrative niche. And he’d done business with Champion-Cain before, lending her money that was repaid with interest. He made a few relatively modest investments in the fund, and after those paid off, he put in more capital. He also spread the word, first to well-heeled associates and later to banks and hedge funds. Collectively, they would invest about $140 million. In 2015, in recognition of his role as the fund’s principal rainmaker, Peterson got a small ownership interest in Champion-Cain’s company and the right to 80% of the fund’s profits.

In fall 2016, Peterson invited a promising visitor to his office in Del Mar, a beach town north of San Diego. Michael Brewer was president of Alcoholic Beverage Consulting Service, a company that offers liquor licensing assistance. Brewer was one of the foremost liquor license experts in the state, and he had name brand clients: CVS Pharmacy, Marriott International, Outback Steakhouse. Such large corporations had no need for Champion-Cain’s fund. But Peterson hoped Brewer’s smaller clients might be interested in borrowing money. Before describing his idea to Brewer, Peterson asked him to sign a nondisclosure agreement. “He thought he found the golden goose,” Brewer tells me.

Peterson explained things to Brewer much as Champion-Cain had explained them to him. But Brewer was perplexed: There’s a difference between the letter of the law and how California liquor licensing really works. Yes, buyers are supposed to deposit the full purchase price of their license into escrow within 30 days of filing an application. In practice, almost no one deposits more than 10%. The agency in charge “never pressures anybody to fund within that 30-day time frame,” Brewer says. Only on the eve of approval are applicants required to have the full amount. That lets them avoid tying up significant resources in non-interest-bearing accounts during a review process that can take a year.

Brewer could think of few circumstances in which he would recommend that clients cover their escrow needs with high-interest loans. “I told Kim Peterson it made no sense,” he says. “He didn’t believe me.” By then, Peterson had been investing with Champion-Cain for about four years. Millions of dollars had flowed through the fund. Peterson had made a handsome profit, and he felt sure of his returns. He was confident that Chicago Title was protecting the loan principal for which he was responsible. Brewer says that Peterson told him, “I’ve got $8 million in loans on the street right now.” (Peterson, who denies naming a specific figure, tells me that before taking on a larger role in the fund, he consulted with multiple law firms and visited the Alcoholic Beverage Control district office in Sacramento to confirm the legality of the lending model. The office didn’t respond to a request for comment.) As far as Brewer was concerned, the problem that Champion-Cain’s fund purported to solve didn’t exist.

The San Diego coast.

Source: Alamy

Amid the surfboards, flip-flops, and fish tacos, it’s easy to forget that San Diego is a Navy town, and its largest employer is the U.S. military. This helps explain the city’s relatively conservative politics and, with the twentysomethings who alight for a few years to enjoy the craft beer scene before seeking fortunes elsewhere, its transience. The motto on San Diego’s seal is Semper Vigilans (Always Vigilant), but boosters prefer a public-relations slogan dreamed up in the ’70s after San Diego was spurned by the Republican National Convention: America’s Finest City.

Until 2019, when she was revealed to be the architect of an almost $400 million Ponzi scheme—a distinction that likely makes her the most prolific female Ponzi artist in history—no one channeled the local je ne sais quoibetter than Champion-Cain. She arrived in 1987, tired of winters in Ann Arbor, where she had grown up and recently graduated from the University of Michigan. Seven years later, having added an MBA to her résumé, she took a job with Koll Co., a large developer. Lynda McMillen, then a regional president, hired her. “She is bright. She is articulate. She has confidence and poise,” McMillen says. “She could go anywhere she wanted to go.”

Champion-Cain inherited a passion for real estate from her father, a developer in Michigan. But she didn’t find the overwhelmingly male world welcoming. Petite, tan, and athletic, with flowing dark hair, she was once told by a senior executive that she was too good-looking to be taken seriously. Plum assignments seemed to go to men, while she was stuck with troubled projects. “I made a name for myself for being able to do complex negotiations and turn around distressed assets,” she said in a 2016 interview for a podcast hosted by psychologist Nancy O’Reilly. But it was a lonely education. “I couldn’t ask the men for help. They would have seen it as weakness.”

Among the notable projects Champion-Cain worked on at Koll were a trio of San Diego retail centers, including the massive La Jolla Village Square. If she felt intimidated by male colleagues, it didn’t show. “She played cards, she drank bourbon, she smoked cigars, she was into going to Vegas,” recalls Howard Greenberg, president of Trilogy Real Estate Management, a prominent landlord. “She could walk into a room full of guys and hold her own.”

In 1997, Champion-Cain left Koll to found American National Investments (ANI), eventually renting a small office above the Onyx Room, a nightclub in the Gaslamp Quarter, in downtown San Diego. The Gaslamp, which encompasses about 16 blocks adjacent to San Diego Bay, was once known for its brothels, gambling halls, porno palaces, massage parlors, and sailor saloons. Since becoming an historic landmark in 1978, the neighborhood had attracted developers, including Trilogy, that were converting its Victorian-era buildings to live-work lofts. The city poured in cash. In 1998 voters approved an expansion of the San Diego Convention Center, along the Gaslamp’s southwest border, and backed a deal for a new ballpark for the Padres blocks away.

The area remained scruffy, but Champion-Cain remembered her father’s perseverance through economic doldrums. In the Gaslamp’s dilapidated buildings she saw a chance to improve her own fortunes and those of her adopted hometown. In 1998, ANI bought the old Woolworth Building at the northern edge of the Gaslamp for $2.5 million. With partners, she spent several years redeveloping a chunk of the block for mixed use, with dining, retail, residential lofts, and a House of Blues.

The project elevated Champion-Cain’s profile, providing a calling card she’d use for the rest of her career. “To see an old, rundown building in the center of town become a completely different type of venue was quite rewarding,” she told the San Diego Union-Tribune. “No one thought I could pull it off.” (After agreeing through an intermediary to be interviewed for this article, Champion-Cain backed out when I declined to sign over any potential film and TV adaptation rights to the intermediary.)

No less instrumental in Champion-Cain’s rise was her relationship with Jack Berkman, a sought-after PR man. Berkman was an early chairman of the Gaslamp’s business improvement district and a co-owner of the now-shuttered Fio’s Cucina Italiana, a beloved, much imitated Italian restaurant on Fifth Avenue. When Champion-Cain approached him about representing her in the late ’90s, he saw a kindred spirit and a highly marketable product.

One morning in July, I meet Berkman at a power breakfast spot not far from the San Diego Zoo. He’s seated at a booth beneath a painting of the principals from The Wizard of Oz following the Yellow Brick Road. “There weren’t a lot of women leading organizations in real estate back then,” he tells me. “Gina stood out. She was warm. She was very charismatic, and she embraced wanting to make a difference.”

They devised a strategy to establish her as a major figure in San Diego and a face of the Gaslamp, which was mutating into a tourist landscape of generic restaurants and Disney-fied historic lanterns and trolley buses. Champion-Cain began picking up awards and appearing on splashy lists: San Diego Business Journal’s Women Who Mean Business award, San Diego Metropolitan’s 40 Under 40, San Diego magazine’s 50 People to Watch. She chaired the Executive Committee board for the Downtown San Diego Partnership, got appointed to the powerful Centre City Development Corp., and associated herself with charities, including the American Lung Association. In recognition of her good works, the mayor once declared June 28 “ Gina Champion-Cain Day.”

In July 2003, Champion-Cain appeared on the cover of San Diegomagazine beneath the question, “Who Owns Downtown?” Standing beside her was Bud Fischer, a co-founder of Trilogy with Howard Greenberg. Greenberg found the pairing odd. At 71, Fischer was a bona fide mogul with decades of experience developing downtown real estate. “And here is Gina, next to him, as if they’re somehow equal,” Greenberg says. The article identified only a single building that Champion-Cain owned—and she didn’t actually own it. “She was the empress with no clothes,” he says.

Champion-Cain at the opening of Luv Surf in 2012.

Photographer: Andrew Oh

After pausing her work during the financial crisis, Champion-Cain reemerged with plans to move into retail and hospitality. In 2011 she bought a sleepy restaurant in Pacific Beach, a low-key oceanfront neighborhood, and converted it into the Patio on Lamont. With an outdoor fireplace, a wall of living plants, and a cheeky cocktail list, it was a hit. In 2014 she opened a second Patio in Mission Hills, the upscale enclave where she lived with her husband, Steve, the owner of a manufacturing company. During the same period she acquired several beachfront homes, converting them into short-term rentals. She opened a boutique, Luv Surf, and teamed up with former Baywatch actress Melissa Scott Clark to open a home goods store. Rapturous news coverage often emphasized Champion-Cain’s fortitude. “When the recession came along, I needed to reinvent myself,” she told San Diego Business Journal. “I had to figure out something else to do besides play golf every day.”

In 2015, Champion-Cain hired Hilary Rossi to oversee ANI’s expanding food and beverage division. She had recently acquired Rossi’s restaurant, Surf Rider Pizza Co., and Rossi was smitten. “She had this crazy energy that was super infectious,” Rossi says when we meet for lunch in San Diego’s Little Italy. Champion-Cain told Rossi about developing Acqua Vista, a well-known condo project nearby. Rossi was impressed: “As a woman in business, I admired the shit out of that.”

In just a few years, ANI had gone from having five employees to hundreds. The walls of a new 26,000-square-foot corporate office were adorned with Champion-Cain’s awards and magazine covers. Soon after Rossi was hired, Champion-Cain gave her a tour. As they descended to the basement, she described a commercial kitchen Rossi was about to see. But when they arrived, they found an unfinished warehouse in disarray. “There was stuff everywhere,” Rossi recalls. “Equipment, boxes of plates, a torn-down wall. Gina had no idea this stuff was there.” Rossi attributed the misunderstanding to Champion-Cain being busy. “But looking back on it,” she says, “what business owner wouldn’t know what’s underneath their feet?”

As she settled in, Rossi, like four other former ANI executives I spoke to, saw a company in chaos. New hires, partners, or consultants seemed to arrive daily, many with ill-defined roles or superfluous assignments. Champion-Cain’s assistant had an assistant. The assistant’s assistant had two assistants. A former vice president says that his assistant’s main responsibility seemed to be walking Champion-Cain’s golden retrievers. Nepotism figured prominently. “Many of these people were friends, or friends of friends,” says Jarrod Zimpfer, a former ANI events manager. “They were definitely not qualified,” and often overpaid. A wine buyer for the Patio restaurants, Zimpfer says, had never studied wine. Until arriving at ANI, the general counsel, an old friend of Champion-Cain’s, spent her career as a public defender.

Employees and potential partners frequently presented Champion-Cain with entrepreneurial ideas. But her enthusiasm for a project often had less to do with merit than the person who proposed it, and ANI was riven by rivalry for her attention. “For one and a half years, I loved working for Gina,” Rossi says. When she flew to Maine to care for her sick mother, Champion-Cain checked in regularly. And like others who enjoyed favorite-child status, Rossi was given far more responsibility than she’d had in previous jobs (restaurant build-outs, franchising plans, a food truck, a coffee company), which made her invested in ANI’s success. Champion-Cain promised that they would get rich together, Rossi says, telling her, “You’re going to retire with me!”

But Champion-Cain appeared uninterested in the basics of running a company. Business plans, inventory management, and projections were shoddily executed or absent; the former vice president says that she seemed unable to parse basic corporate documents. Few ANI businesses turned a profit. Many hemorrhaged cash. Pamela Corey, a former Luv Surf manager, says, “Everybody eventually wondered, ‘Why are we opening another place when the ones we have aren’t making money?’?” Yet Champion-Cain continued to expand, often with ill-conceived ventures: a CBD line, a chocolatier, and more boutiques and restaurants, including a costly boondoggle in Petaluma known as Chicken Pharm. Champion-Cain had a habit of insulting less favored employees behind their backs. “She’d say, ‘That guy’s an asshole,’?” Rossi recalls. Like other executives, Rossi was constantly reassigned to handle emergencies and eventually found she couldn’t keep up: “I was in the doghouse. I was like, I get it, now I’m the asshole.”

Life as a minor hospitality magnate was intoxicating for Champion-Cain. “She got the bug,” Holly Cloud, a friend, says. “Having her own restaurant was sexy: ‘When I walk in, people know me.’?” Zimpfer says that Champion-Cain hosted political fundraisers at Patio restaurants featuring “the crème de la crème of San Diego society” and footed the bill for friends. Among the frequent beneficiaries were Della DuCharme and Betty Elixman, the Chicago Title escrow officers who handled ANI business. Evenings were often alcohol-fueled, and executives got used to wee-hours, all-caps emails. “She’d be texting during a meeting, and two days later you’d get an email,” Rossi says. “You’d be like, ‘Ugh, this is what I just went over.’?”

ANI executives exchanged theories about what was keeping the company afloat. Some guessed it was Champion-Cain’s real estate business. A former development executive says that during his job interview, Champion-Cain indicated that Jack McGrory, a major San Diego investor, would back her development deals. (The ex-executive, like several others, agreed to be interviewed on the condition of anonymity because of nondisclosure agreements or concern that further association with ANI might be career-damaging.)

That proved false. On deal after deal, Champion-Cain backed out at the last moment, antagonizing brokers and lenders. In some instances, the former executive says, she misrepresented facts to wriggle out of agreements. In the case of one short-term rental property, ANI knocked down a building, which the company planned to replace with new construction, before the lender could inspect it, violating the terms of the loan. Expenditures on other purported rental homes appeared dubious. One property was in Carmel, which prohibits short-term rentals in residential areas. Another, a palatial $3.2 million estate near Palm Desert, seemed intended for personal use.

One day the former executive met with other developers about a potential project in Little Italy. To present ANI as an attractive partner, he spoke about Champion-Cain’s commitment to the neighborhood, citing Acqua Vista, the condo she liked to highlight. A representative from Watt Cos., a large developer, looked at him strangely. “He goes, ‘Dude, wait a second. I was there. Gina didn’t do shit. We had to buy her out of that project!’?”

Filings from dueling, now-settled lawsuits between Watt and ANI appear to bear that out. A 2008 statement by a Watt vice president describes Champion-Cain as an intermediary—a recipient of fees for locating the site and “obtaining permits and entitlements.” The vice president said in the statement that ANI was never owner of the Acqua Vista project, “never contributed any funds toward the project, and never had any equity interest whatsoever in Acqua Vista.”

By 2019 former partners and investors had accused Champion-Cain of fraud and breach of contract in almost a dozen lawsuits going back a decade. A 2012 complaint filed by Gary Pace, a pharmaceutical executive, described a $200,000 loan he made to ANI for a project in Oregon. The suit alleged that Champion-Cain used that money to pay other investors, stay current on an Arizona mortgage, and make payments on an option for land. Lawsuits filed by a former partner in 2016 and 2017 accused her of misallocating assets. (Champion-Cain and ANI largely disputed the allegations in suits against them.)

The lawsuits settled quietly. Champion-Cain’s rise overlapped with contractions in the local press that have afflicted newsrooms across the U.S., with the paper of record, the Union-Tribune, cutting more than half its staff between 2006 and 2010. Apparently unnoticed by the media, her legal troubles didn’t tarnish her public image. In photos accompanying celebratory articles about her, she wore patterned dresses and beaded jewelry: an exemplar of a tastefully prosperous San Diego lifestyle. “There’s plenty of people who promote themselves as something that they’re not,” says Greenberg, the Trinity president. “So if she said she did this or that? Maybe she did. And if she didn’t, who’s that harming?”

“I panicked and felt I needed to support an image of who people believed Gina Champion-Cain was”

In January 2019, Brewer, the Alcoholic Beverage Consulting Service president, got a call from a private equity firm that intended to invest about $100 million in Champion-Cain’s liquor license fund. Before pulling the trigger, the firm wanted his read. Brewer drove to the firm’s office in San Diego, where the client showed him the offering documents. He hadn’t forgotten his meeting with Kim Peterson almost seven years earlier. The paperwork deepened his sense that something was off.

The first thing Brewer noticed was that the explanation of escrows omitted that the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control doesn’t immediately require buyers to deposit the full price of licenses. Again, this suggested urgent demand for short-term loans where none existed. A spreadsheet enumerated loans ostensibly made by Champion-Cain’s fund. Several licenses were for wholesalers such as winemakers and breweries. But wholesale licenses don’t require escrows. Why would a business take out a high-interest loan to cover a nonexistent cost? And the prices for many licenses struck Brewer as wildly inflated.

But Brewer’s clients had FOMO. “They were very much wanting to do the investment,” he says. “They felt everybody was getting rich and they were getting left out.” They asked him to help with due diligence. The team contacted every liquor license lawyer and consultant in the state to ask if their clients were using Champion-Cain’s fund. None were. Next, they reviewed about six months of records for liquor license transfers. For every transaction in which Chicago Title—the insurer affiliated with the fund—handled escrow services, the team contacted the buyers and asked if they were using the platform. Again, nothing. To get anywhere near the millions in loans she claimed to be funding, Champion-Cain would have had to be responsible for every single liquor license escrow at Chicago Title. Brewer’s investigation suggested that she was behind none of them. In March 2019, his clients concluded that the likely explanation for the inconsistency was that Champion-Cain was running a Ponzi scheme.

That August the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filed a complaint accusing Champion-Cain of embezzling more than $300 million from investors across the U.S. She hadn’t made a single loan to a liquor license applicant. Instead, investors’ cash was deposited in a Chicago Title account that she controlled exclusively. A U.S. Department of Justice complaint followed. In July 2020, Champion-Cain pleaded guilty to securities fraud, obstruction of justice, and conspiracy. In all, almost $400 million flowed through her fund. All but about $11 million left in her account was used to prop up her businesses, pay off existing investors, and cover expenses including jewelry, cars, credit cards, travel, box seats for the Padres and Chargers, and a $22,000 golf cart.

In a statement submitted to the court, Champion-Cain promised to help investors recoup losses and wrote that she was “seduced and addicted to the appearance that I was enhancing peoples’ lives. Ever since I was a little girl my Mom has told me that all I ever wanted was to take care of people. To be ‘Mama Gina.’?” At sentencing in March, she described how her self-reliance curdled into something toxic. “I kept trying to pull deals together, to be creative in the re-creation of my business, but I kept failing,” she said. “I panicked and felt I needed to support an image of who people believed Gina Champion-Cain was.”

Unmoved, U.S. District Judge Larry Burns sentenced her to 15 years in federal prison, about four more than prosecutors recommended. It rankled the judge that Champion-Cain’s victims included friends, family, and employees. “This wasn’t just strangers hoping to get rich,” he said, explaining how her “deceit and betrayal” played into his sentencing rationale.

Still, much of the money came from supposedly sophisticated investors and financial institutions. They’d put their trust in Chicago Title, the company theoretically safeguarding their capital. By the time of Champion-Cain’s indictment, ANI had little value and Chicago Title had become the target of lawsuits. Several have settled, with Chicago Title paying about 65¢ on the dollar against losses without admitting wrongdoing. Others are ongoing, including a joint suit by Banc of California Inc. and the Texas hedge fund Ovation Partners, as well as one by Kim Peterson. (Peterson has never been accused of wrongdoing by the SEC or Justice Department.) Chicago Title didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The lawsuits turn on the company’s evident failure to safeguard against fraud and investigate obvious irregularities with Champion-Cain’s account. The most glaring was that hers had no finite purpose. Escrows generally close within months, but Champion-Cain’s stayed open for years. In an unusual arrangement, Chicago Title collected steep usage fees; one lawsuit estimates that the company made hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions, from its relationship with Champion-Cain. Effectively, these were very profitable checking services.

To deceive investors, Champion-Cain impersonated Chicago Title employees, creating fake email addresses and forging documents and signatures. But she had inside help. The escrow officers who handled ANI business, DuCharme and Elixman, were aware of her impersonations. Documentation presented in lawsuits against Chicago Title suggests that they also lied to investors and auditors—confirming, for example, the value of investments held in escrow accounts that didn’t exist. In return, they got plane tickets, personal checks, and Patio dinner parties on the house.

In much the way she groomed employees, Champion-Cain nurtured her relationship with DuCharme in particular, holding out the promise of a life that, absent their association, would’ve been impossible. Champion-Cain paid for DuCharme’s son to fly to Michigan to visit Champion-Cain’s alma mater. DuCharme badly wanted to own a home, and Champion-Cain arranged to buy a four-bedroom house in the desirable neighborhood of Point Loma Heights and rent it to DuCharme cheaply on a lease-to-own basis. Right around this time, the scheme was exposed, and DuCharme never moved in.

Champion-Cain called DuCharme and Elixman endearing nicknames—Lovie and the Boopster, respectively—and denigrated mutual acquaintances: Prick, Idiot, Grumpy, the Doughboy. Their correspondence speaks to the foxhole psychology of an embattled sisterhood. “No matter what I would kick asses for you G!” DuCharme wrote to Champion-Cain in November 2015. At ANI, Champion-Cain insisted that all real estate escrow work go to DuCharme. “She would not do a deal unless Della was involved,” the former development executive says. “Gina was protective of her, like a mother bear.” Benjamin Galdston, a lawyer representing investors in a suit against Chicago Title and the two women, says, “Gina made them feel special. She made them feel valued.” He adds: “They had this secret together. They were truly co-conspirators.” (Both women were fired from Chicago Title. Elixman’s lawyer declined to comment. DuCharme’s lawyer didn’t respond to a request for comment. According to court filings, both women are being investigated in the ongoing Department of Justice probe that resulted in Champion-Cain’s indictment.)

Champion-Cain in 2015.

Photographer: John Gastaldo/San Diego Union-Tribune/Zuma Press

In November 2019, before Champion-Cain’s sentencing, Pamela Corey, the former Luv Surf manager, went to her home for Thanksgiving. It was a small gathering that included Champion-Cain’s parents. Corey, who was in her early 30s, had moved to San Diego from outside Boston in 2014 to work at the boutique. She’d read about Champion-Cain in magazines. From a distance, she looked up to her; when they met, Corey found Champion-Cain warm and compassionate. Corey’s father died in October 2018. She didn’t have family nearby, and Champion-Cain invited her over for holidays and Super Bowl parties. Corey loved her job—the parties she hosted at the shop, the buying trips to Los Angeles, the fact that she could bring her labradoodle to work. Champion-Cain always turned up at her events, and Corey saw a promising future with ANI. “Gina would say, ‘We’re looking for another boutique for you,’?” she recalls.

Earlier in 2019, Corey had invested $20,000 in Champion-Cain’s fund, money she inherited after her father’s death. When reports of a Ponzi scheme surfaced, she was shocked. She thought it was a misunderstanding that her friend and mentor would surely correct. “We were like family,” Corey says. “Your mind tricks you.” By Thanksgiving the truth had become clear. “She told me she felt relieved, that she didn’t have to be anxious anymore,” Corey says. But Corey remained attached. Like many in Champion-Cain’s orbit, she struggled to square the person she knew with what that person had done.

Now, Champion-Cain had one last plan to make things right. Her house in Mission Hills was elegant but homey. In the kitchen before dinner, standing at the sink working on a meal of mashed potatoes, turkey, and cranberry sauce, she explained her vision. “She said, ‘I’m going to get all your money back,’?” Corey recalls. There would be a film about her life, Champion-Cain said, a deal with Amazon.com Inc. or Netflix Inc. worth millions of dollars. Champion-Cain’s part might be right for a big-name actress—maybe Demi Moore, to whom she bore some resemblance. Corey, Champion-Cain assured her, could play herself. How the project would come together was unclear. There was no evidence that it existed. But when she described the movie, it seemed real. For a while, Corey believed her. Champion-Cain had always been a wonderful storyteller.

Read next: Covid Was a Boon to Heists, Hoaxes, Scams, Cons, and Mischief

Sent from my iPad |