Re below article, I am agnostic w/r to correctness and in truth do not much care, because am fairly sure Team China shall do whatever and Team USA shall do whatever else, and the only way to tell what works for which Team require wait & watch given that all the pieces are dynamic

But, the elements and string of the article shall be a/c for in forward processing

However, an observation, what in China China China passes for sandbox play session is apparently considered as strategy by FT, perhaps has something to do w/ election cycles and such

ft.com

America’s lopsided China strategy: all guns and no bread and butter issues

The administration is preparing an economic plan for the Indo-Pacific, but it will not include access to the US market

6 hours ago

© FT montage; Getty Images

Admiral John Aquilino, the top US military commander in the Indo-Pacific, recently held an unusual meeting with the head of US Space Command and deputy head of US Cyber Command — in a remote part of the Australian outback.

Aquilino and his colleagues, General James Dickinson and Lieutenant General Charles Moore, had flown all the way to Alice Springs, a dusty town in central Australia for sensitive talks on China with top Australian officials at Pine Gap, a top-secret spy satellite facility run by the CIA and the Australian government.

Speaking before their meetings, Aquilino and his colleagues stressed that their visit to Australia was part of a strategy US president Joe Biden has made central to his foreign policy: working more closely with allies and partners to counter China.

“We’ve a few targets,” Aquilino, a former Navy “Top Gun” fighter pilot, said in an interview with the Financial Times. “Number one is highlight the strength of allies and partners to deliver integrated deterrence and prevent conflict here in the Indo-Pacific.”

Washington may be completely immersed in the war in Ukraine, but the Biden administration is also focused on what it sees as its biggest long-term objective — developing a coherent strategy to deal with China.

After the turbulence of the Trump years, when the administration’s hawkish tone on China was consistently undermined by spats with allies, the Biden team is going out of its way to ensure that the US and its partners are closely aligned on China.

As part of that effort, Aquilino spent six days in Australia. Over the past 15 months, the president has reinforced alliances with Japan, South Korea, New Zealand as well as Australia; worked hard to involve India more in China policy; boosted co-operation with European nations from Britain and France to Germany and ratcheted up support for Taiwan.

Yet while Biden has won praise from allies for the security component of his Indo-Pacific strategy, many have been frustrated at what they see as a gaping hole: the lack of a trade and economic agenda. For some critics, an appealing economic strategy is essential to bolstering US leverage in Asia and making sure countries are not too economically reliant on China.

“There has been a real vacuum in American trade policy towards Asia,” says Sheena Greitens, a China expert at the University of Texas in Austin. “Asia is moving ahead on regional trade integration, with some willingness to include China, while the US has been largely absent.”

Biden is hoping to shrink that gap this summer with the launch of an Indo-Pacific economic framework (IPEF). The plan will contain include elements that range from fair trade — including labour and environmental issues — to secure supply chains, infrastructure, clean energy and digital trade.

According to an official from a country in the Indo-Pacific, some Asean countries are very interested, for example, in a digital trade agreement that would set rules for the road.

Admiral John Aquilino, left, head of the US Indo-Pacific Command, looks at videos of Chinese structures and buildings on board a P-8A Poseidon reconnaissance plane flying over the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea in March this year © Aaron Favila/AP

However, it will crucially not include any new access to the US market for products from Asian countries — a reflection of the increasingly tough politics surrounding traditional trade agreements that became so ingrained during the Trump years and which Biden remains sensitive to, particularly ahead of November’s congressional midterm elections.

Critics say that without a strong trade policy, the US risks ending up with a lopsided approach, heavy on military presence but light on economic engagement, which leaves its allies hesitant about its genuine commitment to the long-term future of the region.

Another Indo-Pacific official says countries in the region appreciate that Biden is finally engaging on trade, but adds that the lack of market access is a significant setback.

“It is like a fried egg without the yolk,” he says.

A troubled relationship

Biden has struck a more hawkish tone on China than allies had expected. He has taken Beijing to task over everything from its repression of Uyghurs to its military activity near Taiwan. China in return accuses the US of being a fading hegemonic power and says the days of it being bullied are over.

While Biden and Xi Jinping, his Chinese counterpart, have boosted their personal engagement in recent months, US-China relations are mired at their lowest level since the nations normalised diplomatic relations in 1979.

Biden’s China policy has several goals. He wants to shape the international landscape to raise the cost to China of engaging in coercive behaviour. He also hopes that showing a united front with allies such as Japan and Australia will send a strong signal about deterrence to China and make Xi think twice about invading Taiwan. And he wants to establish what his team describes as “guardrails” to avoid competition veering into conflict.

During his visit to Australia, Aquilino visited US marines who are stationed in Darwin as part of the push to position more US military resources in the region. At Amberley air force base, he greeted a B-2 stealth bomber that had flown from the US in a move that was partly aimed at reminding China about the potency of American military force.

In another example of co-operation, the White House recently said it was expanding Aukus — a security pact the US, UK and Australia agreed last year — to work together on hypersonic missiles. China reacted angrily to Aukus, which will help Australia get nuclear-powered submarines. It views the pact in a similar vein to the “ Quad” — the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue grouping of the US, Japan, Australia and India — which Biden has also reinvigorated.

Biden has also had success persuading European nations, particularly Germany, which were previously wary about upsetting Beijing to take a tougher stance on China.

Yet despite his efforts to deepen relations with allies, Biden has not yet persuaded Xi to reduce coercive activity in Asia. Paul Haenle, China director at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think-tank, says the focus on allies is critical but China is “not playing ball”.

“They do not buy the notion that the change in China’s policies, behaviour, actions and rhetoric under Xi Jinping is contributing in any way to the downturn in US-China relations,” says Haenle, who stresses, however, that Biden should continue to set the table for strategic negotiations in the future and that trade is a critical component.

“The risk is that the optics in the region become the US coming to the table with guns and ammunition and China dealing with the bread and butter issues of trade and economics.”

An alternative framework

Over the next few months, the Biden administration will make its pitch to revert that impression with the launch of its new economic framework.

A third official from the Indo-Pacific says IPEF is a start that may lead to something more substantive. “They need to stretch their muscles a little and get match fit before they can do something serious,” the official says. “It’s sort of like a no-contact pre-season game.”

In an ideal world, allies would like the US to re-join the Trans-Pacific Partnership — a 12-nation trade deal signed in 2016 that Donald Trump left in 2017. But they recognise that big trade deals are now political kryptonite in America. Even before Trump pulled out of TPP, Hillary Clinton, his Democratic rival in the 2016 presidential race, had withdrawn her support.

China in January signed a trade agreement — the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership — with the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations along with Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand © Cui Liu/VCG/Getty Images

Yet the stakes have become higher since Beijing last year applied to join “TPP-11” — the revamped successor to TPP, which the US had championed to counter China’s growing economic clout. In another example of that influence, China in January signed a trade agreement — the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership — with the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations along with Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

Matthew Goodman, a trade expert at CSIS, a think-tank, says Biden hopes his new framework will make up for the US not being in TPP-11. “The administration has put forward this framework as an alternative it thinks countries in the region will be drawn to and there’s reason to believe they will,” says Goodman, referring to elements such as the digital component.

A US official dismisses suggestions from experts that some countries are less interested in the framework. “There was sort of an assumption in the Washington policy community that if you didn’t do TPP, everyone would just sort of scoff at it,” says the US official. “We’ve been very pleasantly surprised at how much interest there is.”

Xi Jinping meets with Joe Biden via video link in Beijing in November 2021. Relations between China and the US remain at their lowest level since they normalised diplomatic relations in 1979 © Chine Nouvelle/SIPA/Shutterstock

One person familiar with the IPEF discussions says the US is focusing its negotiating efforts on eight countries: Japan, Australia, New Zealand, India, Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia. Countries will be able to join some of the IPEF pillars without committing to all four. She stresses that the fact that there are eight countries engaging in serious discussions does not mean all of them will join the framework at the start.

The person familiar with the talks says many nations are interested in a possible digital trade deal. She says American CEOs who talk to the administration are as interested in common rules and standards for digital trade as they are in traditional trade arrangements.

While Goodman welcomes the framework, he cautions that there are many unanswered questions. First, Biden must convince countries that it will stick, given what happened with TPP. Some in the region also worry what will happen if Trump returns to the White House in 2025.

Goodman says some countries are also concerned that Biden has split responsibility for the framework between the US trade representative office, led by Katherine Tai, and the commerce department, led by Gina Raimondo.

“One major challenge for this initiative is that here is no single senior official in the Biden administration who clearly owns this patch,” says Goodman, who adds that Raimondo would be the obvious candidate since the commerce department is charged with helping American companies expand their overseas trade opportunities.

Wendy Cutler, a former top USTR official now vice president of the Asia Society Policy Institute, concedes that the lack of market access is a “big hole”, but she stresses that critics should wait for the release of the full framework before judging.

“I’m optimistic it will address the concerns expressed by many that we don’t have an economic agenda for the region. But it’s going to be a different agenda and people need to keep an open mind,” says Cutler, who adds Biden should prioritise digital trade. “Our partners in the region are moving forward to set rules without us.”

Joe Biden has split responsibility for the IPEF framework between the US trade representative office, led by Katherine Tai, centre, and the commerce department, led by Gina Raimondo © Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images

Some experts worry that the lack of traditional tariff reductions may handicap the US, which has traditionally used it as a carrot to get countries to sign up to trade-related measures. But Tai recently told Congress that the lack of market access did not mean that the US was proposing something that would not be “economically meaningful” for the region. And US officials argue that the IPEF includes measures — such as digital trade — that are more suited to the current global trading system.

That will depend on what Washington is offering the other nations. “A lot of countries are asking ‘What’s in it for us?’” Goodman notes.

“We want something that very clearly shows that there are benefits?.?.?.?for American workers and American businesses, as well as for our foreign partners,” says the US official. “How we land that is going to be a challenge.”

Ami Bera, the Democratic head of the House foreign affairs Asia subcommittee, believes it is “too tough politically” to re-join the pact but says the framework will increase economic engagement with the region. “As we start to put real meat on the bones of the Indo-Pacific framework, this is an opportunity,” says Bera, who says it is important that India, which has not joined TPP, will be involved in the IPEF.

The Taiwan complication

As the administration tries to develop its new economic approach to the region, one complicating factor for the White House has become Taiwan — especially given the way Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has focused attention on the risk of a Chinese attempt to take the island.

Some US officials want to include Taiwan, over which China claims sovereignty, to give it more of a formal role in the international system. But others subscribe to the view held by some countries in the region that allowing Taipei to join the framework would make it difficult for them to participate because of a likely backlash from Beijing.

“The administration needs to balance participation by Taiwan with their efforts to attract as many partners in the region as possible,” says Cutler.

Complicating matters further, a bipartisan group of more than 200 US lawmakers recently wrote to Tai and Raimondo calling for Taiwan’s inclusion to “send a clear signal that the US stands with its allies and partners and will not be bullied by?.?.?.?China”.

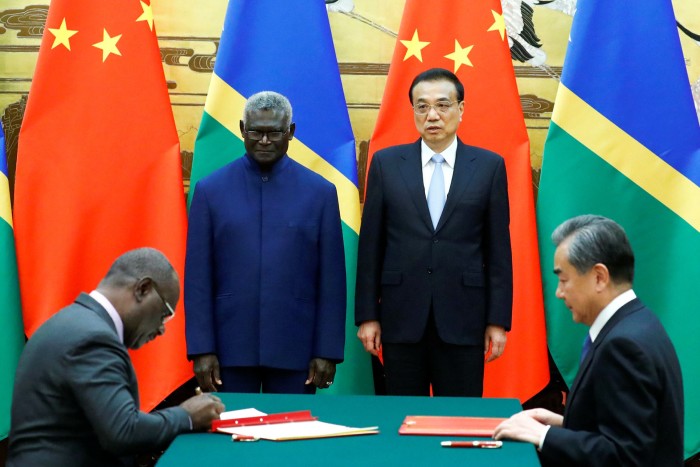

Jeremiah Manele, Solomon Islands foreign minister, Manasseh Sogavare, the prime minister, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and Chinese state councillor and foreign minister Wang Yi attend a ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in 2019. The Solomon Islands, which has signed a security pact with Beijing that some worry could lead to China building a naval base in the South Pacific nation, has not had a US embassy since 1993 © Thomas Peter/Pool/EPA-EFE

Tai has refused to say if Taiwan will be included. But the person familiar with the situation did not include Taiwan in the list of the eight main countries.

As the administration edges closer to launching IPEF, it has been served a stark reminder of how not being fully engaged in the region can open the door to China.

Kurt Campbell, the top White House Asia official, and Daniel Kritenbrink, the top state department official for the region, last week visited the Solomon Islands. The pair travelled to the South Pacific nation after it signed a security pact with Beijing that some worry could lead to China building a naval base in the country, which has not had a US embassy since 1993.

“The Solomon Islands is probably a good example of how we are falling short in areas where the region needs help and the Chinese are filling that void,” says Haenle.

But Kritenbrink rejects suggestions that the US had not been engaged with the Solomon Islands, listing several examples such as the provision of more than 150,000 Covid-19 vaccines in recent months, and adding that economic links were “an important component” of US policy towards Pacific Island nations.

“The central pillar of our entire strategy and engagement with the Indo-Pacific is revitalising our ties with allies, partners and friends,” he says.

Greitens applauds the new focus on economic issues, but believes it is insufficient. “IPEF is welcome but there are a lot of unanswered questions, and frankly it’s unlikely to be enough to resolve some of the big concerns,” she says. Cutler adds that the administration should have already unveiled the framework, saying, “the fact that the initiative hasn’t been launched yet diminishes the credibly of the administration”.

A second US official, who says the White House hopes to finalise IPEF by mid-June, stresses that the administration is trying to find a pragmatic approach that will help both the US middle class — which has been one of the key mantras of the Biden administration — and countries in the region.

“It’s taking a different form than the cookie cutter free trade agreement and so?.?.?.?it’s taken a little while,” she explains.

Follow Demetri Sevastopulo on Twitter |