Someone saw it coming ... someone always does

bloomberg.com

Meet the Hedge-Fund Manager Who Warned of Terra’s $60 Billion Implosion

Kevin Zhou of Galois Capital says he started warning about Terra as a ‘public service to also let everybody else know’ about its dangers.

The Luna token price on the Terra Station Dashboard on April 10.Photographer: Tiffany Hagler-Geard/Bloomberg

By

Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway

16 May 2022, 04:00 GMT+8

Hacks, scams, ponzis, rug pulls and crashes are common in crypto; they happen almost every day. The recent collapse of the Terra ecosystem and its UST stablecoin is different.

Terra was pitched as an important experiment — an attempt to create a stablecoin pegged to the US dollar without relying on traditional financial securities or overcollateralized crypto assets as reserves. Last week’s sudden collapse of the Terra project now puts that idea in doubt, and its loudest critic is claiming victory.

It’s a dramatic reversal for the coins involved. At its peak in early April, the market value of all Luna — the tokens that back the Terra stablecoin — was a stunning $41 billion-plus, according to CoinGecko, placing it firmly in the top 10 cryptocurrencies. Until just a few days ago, there was almost $19 billion worth of UST.

Unlike many crypto projects, which are niche and confined to hardcore traders, Terra went mainstream. It was backed and promoted by what parent company Terraform Labs trumpeted as its “all-star roster of investors” including Arrington Capital, Delphi Digital and Pantera Capital. It’s also a sponsor of the Washington Nationals baseball team, and has a huge army of self-described “Lunatics” who avidly promoted the project across social media. Galaxy Digital LP Chief Executive Officer Michael Novogratz, who invested millions in the endeavor, unveiled a Luna tattoo back in January.

Terra’s outspoken founder, Do Kwon, is one of the main characters on “Crypto Twitter,” often sparring with critics who warned the project would end badly. The most high-profile of those critics was Kevin Zhou. Zhou is no crypto skeptic, having been in the industry since 2011, working at an early exchange called Buttercoin before running trading at Kraken. In 2018, Zhou launched his crypto hedge fund Galois Capital, named after the French mathematician who died in a duel.

Kevin Zhou of the crypto hedge fund Galois Capital warned the industry about the Terra implosion.

Source: Kevin Zhou

In an interview with the Odd Lots podcast, Zhou says he began to worry that Terra posed a “systemic risk” to the entire crypto space, and that he started to tweet about its dangers “as a public service to also let everybody else know too.”

Indeed, Zhou has been strenuously warning about the risks of Terra/Luna on Twitter since the beginning of this year, portraying himself as “Rome” going head-to-head with Kwon’s “Carthage.” Last week, the historical analogy was borne out; tens of billions of dollars in value have been wiped out with little sign of recovery. A spokesperson for Do Kwon declined to comment for this piece.

To understand what went wrong, it helps to explain how Terra was supposed to work — and why it’s so unusual among the multitude of crypto-inventions that have sprung up in recent years.

Twitter

The Ultimate Box

In the volatile and fragmented world of cryptocurrencies, stablecoins are a way to move money around with the confidence that you won’t suddenly lose a large sum of it. To maintain a steady value — usually a peg that tries to stay as close to the US dollar as possible — many of these coins are backed by securities like Treasuries or cash reserves, or are overcollateralized with some combination of crypto.

But UST tried to do something different. Instead of using assets to maintain its peg, it depended on an algorithm and an arbitrage mechanism — essentially a promise that one UST would always be redeemable for $1 worth of the Luna token.

If Luna is worth $1, then you could swap one UST for one Luna token. If Luna rose to $100, then one UST would entitle investors to 0.01 Luna and so forth. For crypto proponents who distrust fiat currencies, the ability to create a stable currency without links to the traditional financial system is an important goal.

Stablecoins are a key feature in decentralized finance, or DeFi, allowing investors to transact in cryptocurrencies and digital assets. They are used in a wide variety of lending, borrowing, trading and yield-farming programs. Despite the money pouring into the space and seemingly high returns on offer, it’s still unclear where a lot of that yield comes from.

In an Odd Lots interview last month, Sam Bankman-Fried, the CEO and co-founder of the exchange FTX, described DeFi as basically a magic box.

People put their money into a box — incentivized by the award of some token — and then more money goes into the box. Over time, the box is worth a lot of money. And maybe the box becomes a bank or culminates in some other important project, but it doesn’t really matter so long as you get into the box early and sell before everyone else.

According to Zhou, Luna was not just any “box,” but a particularly egregious one that was designed to enrich insiders. While the Luna/Terra arbitrage kept the two assets steady in terms of their relationship with each other, it was the eye-popping yields of almost 20% on offer in the project’s Anchor Protocol that lured them into the ecosystem in the first place.

“I would say that certain boxes are a little bit more honest in the sense that it’s kind of like a chicken game. It’s users competing with users and the earlier you are, the better that you do. I know it sounds really bad. It is really bad,” he said. “But what I’m saying is that this is even worse than that because it’s not really just users competing against users. It’s more like users thinking they're competing against other users, but really getting all their funds siphoned out by investors and the inside team.”

Twitter

Luna’s Private Stash

So where did that promised 20% return come from? Technically speaking, it came out of a private stash of the Luna token, which was held by Terraform Labs.

When “the Terra ecosystem first got started there were some funds that were set aside for the company itself. And the main company is Terraform Labs and they have this huge stash of Luna, which unlocks over a certain vesting schedule,” Zhou said.

“So what they would do in order to finance their operations and to also finance the Anchor Yield Reserve, they would sell large clips of this to willing investors at some kind of discount that also has a one-year cliff or some kind of vesting schedule, something like that. And then they would use that for operations and they would also use that to keep basically topping up the Anchor Protocol on their yield reserve,” he added.

Zhou also gave a simpler explanation for where the 20% return came from. “What I always like to say is that most of the time if you can’t find where the yield is coming from, then effectively it’s coming from future ‘bag holders,’” Zhou said.

“If you can’t find where the yield is coming from, then effectively it’s coming from future ‘bag holders’”

The entire crypto system is arguably riven with this phenomenon. Yield comes from the assumption that someone else will bring new money into the system. New “bag holders” enter the game and pay out yield to the existing ones. What made Terra stand out was the huge yield on offer in its Anchor program, giving investors the impression of significant upside with potentially little risk.

This is also what made Luna grow so extraordinarily in such a short period of time. Of course, this type of growth hacking can be fantastic, but it can also be a curse. And in some respects, Luna became a victim of its own success, draining reserves at an incredibly fast pace by a burgeoning community of UST holders who were eager to nab those 20% returns.

Read More: King of the ‘Lunatics’ Becomes Bitcoin’s Most-Watched Whale

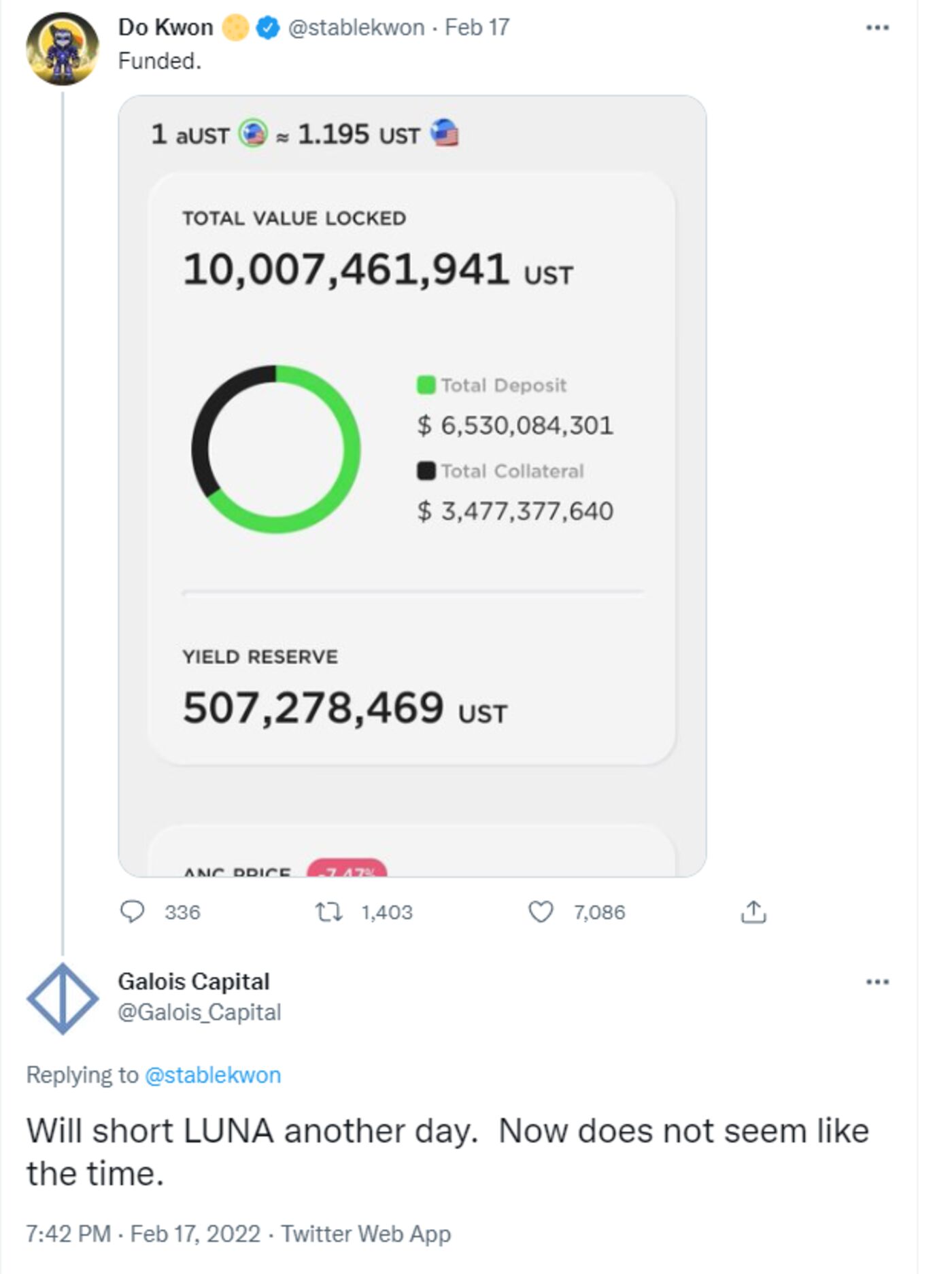

“I think at the peak they were burning maybe about $7 million a day of their yield reserve,” Zhou says. “And originally I think [reserves were] something like $50 million or $80 million or something like that. And then they had to do a top-up of $450 million. And then, you know, very quickly, soon after that was almost depleted and they were thinking about how much to do another top up.”

In theory, Terra could have lowered its offered yield, and slowed down its cash burn, but that would risk investors abandoning the UST ecosystem entirely.

Perpetual Motion or Rube Goldberg?

One way to think about Luna is that it’s a perpetual motion machine, something doomed to fail as the energy needed to sustain it eventually dwindles to nothing. But another way to think of it is as a Rube Goldberg machine in which, as Zhou puts it, “someone’s turning a hand crank to keep the system going.”

Terra arguably had two hand cranks to keep its mechanisms operating. The first was the private stash of Luna tokens, which could be liquidated to keep UST holders happy. But then also this year, the Luna Foundation Guard (LFG; technically a Singapore-based non-profit designed to promote the Terra ecosystem) started building up a war chest of Bitcoin that could be deployed to intervene and stabilize the peg when needed.

In doing so, they borrowed from the world of traditional finance — essentially building a buffer of big FX reserves in the same way that central banks or governments do in order to deploy when they need to defend their currencies. While such a move might work for fiat authorities, it signaled to Zhou that there was a major problem with the Terra/Luna model.

For a start, Bitcoin is highly volatile. For a stablecoin pursuing “stability,” putting assets in a combustible cryptocurrency might provide very little ballast in times of trouble. The Bitcoin stockpile is also finite. Yes, you can spend it to bolster UST, but eventually you run out unless you have some way to secure an ongoing supply — and you might end up playing an intense game of poker with the market.

For Zhou, there was an even bigger problem with Terra’s Bitcoins. The whole project is supposed to be self-righting, with an advanced algorithm dedicated to keeping Luna and Terra on an even keel. By buying Bitcoin, Terra was implicitly suggesting that it hadn’t built a machine that could run on its own.

“It’s destroying their own narrative because, like, they basically said that, ‘oh, we finally constructed this perpetual motion machine. Behold, everybody, we finally did it, you know, and it’s working and it’s amazing. But actually, you know, just in case it doesn’t work, let’s get some insurance,’” Zhou said.

Too Dangerous to Short

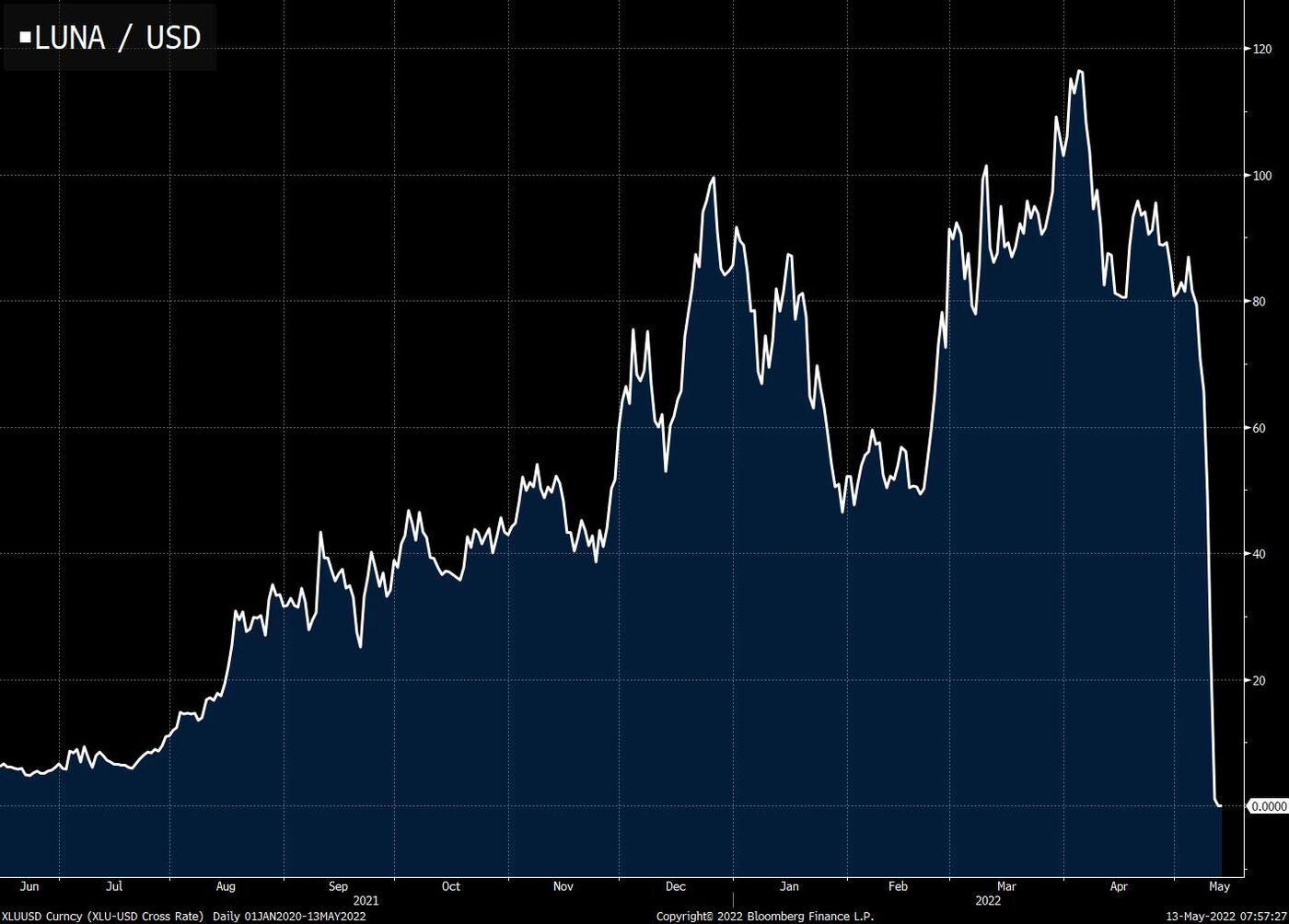

While Zhou had identified vulnerabilities in Terra/Luna for a while, he hesitated to bet against it. As the old adage goes, markets can stay irrational for longer than you can stay solvent, and Zhou didn’t see that changing anytime soon. Last summer Luna was trading around $5. By April it was closer to $120. The machine was still going.

The rise and fall of the Luna token

Bloomberg

Arguably, Luna was benefitting from the overall bear market in crypto that started last November. If everything’s going down and you want to be “safe,” but stay in crypto, you might park your money in stablecoins. Stay in the ecosystem, but try to avoid the overall volatility. And since UST was the highest-yielding stablecoin, and Luna was so closely linked to UST, for a few months Luna almost acted as a negative-beta asset that could be used to hedge the overall market — a dynamic which no doubt bolstered the confidence of many Lunatics.

All of this meant that shorting Luna was extremely risky, even if you understood that ultimately the ecosystem couldn’t be sustained without continuous inflows of more money. In fact, Zhou said as much publicly in February, that it wasn’t yet the time to bet against the Rube Goldberg.

Kevin Zhou promising to short Luna at some point.

Twitter

The Moment

But in May, as crypto markets began to fall and assets which had seen their valuations soar in recent years tumbled back to earth, Zhou was watching. Also in his sights was the drama unfolding on a decentralized platform called Curve. An automated market maker similar to Uniswap, Curve comes with a charming 8-bit Nintendo aesthetic and is designed specifically to swap stablecoins.

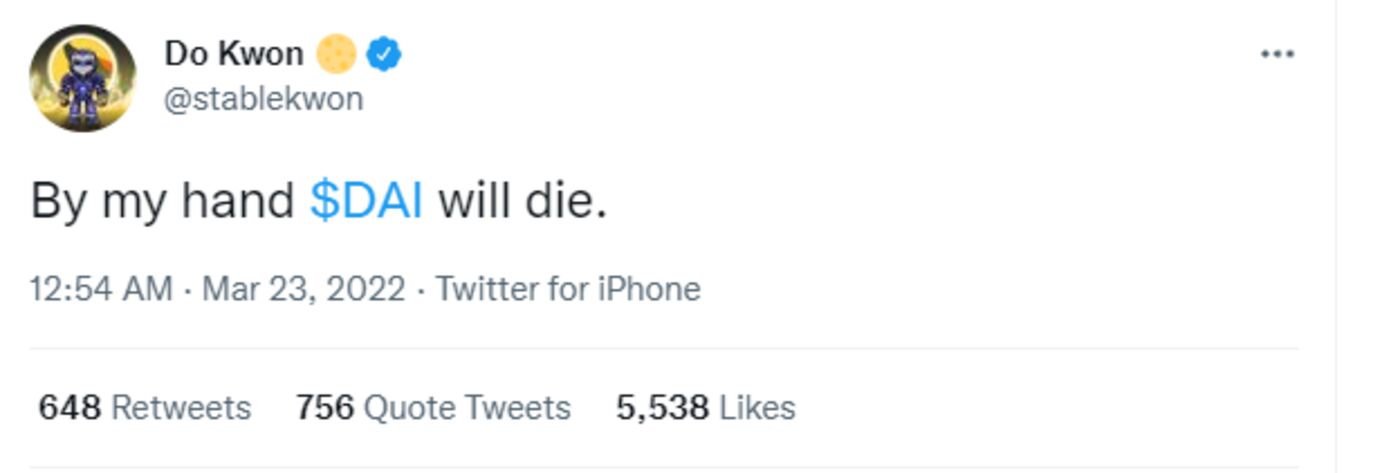

UST traded on Curve against a group of other stablecoins (USDC, Tether, and Dai), which was called 3Pool. As Zhou puts it, UST was acting a bit like a “sidecar” arbitrarily attached to this group of stablecoins. But there was a plan underway to create a new basket called 4Pool, which would include USDC, UST, Tether and another stablecoin called Frax. The goal was to kick out Dai, a coin which Do Kwon effectively saw as a rival.

Luna’s creator promising the demise of a rival

Twitter

Around May 7, someone (or multiple parties) appeared to make a huge sale of UST, swapping it for USDC, Tether and Dai. While Curve is optimized to trade stablecoins in large sizes, the selling was so big that UST liquidity basically vanished and the first real deviation from the peg emerged.

Twitter

“Other assets were drained from these pools,” Zhou explains. “And that basically caused a little bit of a panic. Other people pulled money out of Anchor. People tried to find ways of getting rid of their UST. Luna started tanking. The entire markets were already tanking. It was kind of like an alignment of the stars. The equity markets were tanking and cryptos are correlated with the equity markets these days. So everything was dropping and on top of that the migration was happening. So it was a cacophony of the perfect sequence of events.”

The trades have since become a linchpin around which a variety of conspiracy theories are now swirling. Who exactly sold UST in such large chunks? Was it intentionally done at a time when Luna was preparing a migration to 4Pool — and might therefore be illiquid and vulnerable? Was this a George Soros-breaking-the-pound style trade? Or was it just a panicky market and a bunch of money attempting to exit a stablecoin that was thought by many to be particularly risky?

Regardless of who might have made the trades and why, this is the moment when it all started unravelling, and an event that blockchain archeologists will probably be exploring for a long time. The siege of Carthage had begun.

Fast Spiral, Slow DeathLooking back, it’s rather remarkable how quickly it all unwound. A few weeks ago, there was more than $60 billion in market cap in Luna and UST. Then just over a week ago it started to crack. Now it’s a number swiftly approaching zero. In Zhou’s telling, once the machine started malfunctioning, it was difficult to stop.

“This thing is a purely reflexive asset,” he said. Once the mechanism broke down, there were no curbs. No natural circuit breakers. No emergency lending from the Federal Reserve, no bailout from private investors (there were suggestions at one point last week that external help might be on the way). There’s no natural cash flow that would entice a crypto Warren Buffett to step in and buy the thing for cheap.

But after the fast downward spiral came the slow death. Throughout all the drama, the UST/Luna swapping mechanism was still operating. UST sellers were still theoretically entitled to a dollar’s worth of Luna. But what that meant was that as Luna crashed, the system had to create more and more tokens to meet UST redemption demands. If a Luna is worth a dollar, then a UST holder is entitled to one token. But if Luna is worth 10 cents, then a UST holder is entitled to 10 tokens.

As Luna plunged, more and more Luna were created. That caused the price to plunge even more as holders were massively diluted. That, in turn, meant that the next round of UST redeemers required even more Luna, exacerbating the already dramatic downward spiral. It effectively meant that a cryptocurrency that had been often pitched as a hedge against inflation was effectively being slowly inflated away.

“This is actually worse than hyperinflation,” said Zhou. “It’s hyperinflation of hyperinflation.”

“This is actually worse than hyperinflation,” said Zhou. “It’s hyperinflation of hyperinflation.”

By the morning of May 13, one Luna was down to $0.00001834 and the total supply of the coin was over 6.5 trillion.

Pedal Hard Enough

Despite the spectacular implosion of Terra, it seems likely that the crypto community will not give up its pursuit of a coin that can maintain a stable value while not relying on money in a bank account, or on overcollateralization of other crypto assets as backing.

Last month, Sam Kazemian, the founder of the stablecoin Frax, wrote to Bloomberg Opinion columnist Matt Levine to explain how his coin would evolve: “Our own structure is 1.) not-ponzi, 100% backed normal bank 2.) acceptance, slowly unbacking 3.) permanence 4.) THEN finally ponzi like the Fed/USD.”

In other words, the dream is that if you pedal hard enough in the beginning by creating a backed stablecoin, then over time you can remove the backing because everyone will just accept that the coin is worth a dollar — even when the mechanism to enforce the peg goes away. For crypto adherents, it’s not too dissimilar to how they view the history of the dollar. The greenback built up its power by being backed by gold, they say, but eventually departed the standard once it had cemented its status.

Of course, the dollar doesn’t need to be pegged to a dollar. It simply is the dollar. What’s more, there are all kinds of mechanisms in place that bolster the US currency’s value, including taxes which enforce the need to hold it in the first place. But again, one of the core ideas in crypto is that if everyone just believes hard enough, then you can create something of value. And arguably that idea has proven itself out with Bitcoin, which is not backed by anything except the beliefs of its various HODLers.

Still, the Terra episode is already a huge black eye for crypto and one that might not be forgotten for a long time. Many retail investors have been devastated, with stories of life savings lost and suicide attempts now darkening message boards that were once full of encouragement about going “to the moon.”

Big names in the space will have to answer for how they could get behind such a disaster. Even crypto investors without direct Terra exposure are sitting on big losses because of this. Still, Zhou warns that monetary losses and reputational damage could have been much worse.

“Better that this happened now than later. You know, if UST was $100 billion and eventually there was $95 billion of bad debt, or $90 billion of bad debt, I mean, it would be way more devastating,” he said. “Even more people would’ve lost their shirts.”

Carthage was eventually rebuilt, and it seems likely that someone else is going to try again to build that magic coin. That would be a coin that’s decentralized, not reliant on assets to back it, and still able to maintain its peg — like a top that can spin forever after getting its initial twist. |