Whale oils were also used to make high quality lubricants which were thin, didn't corrode metals and remained liquid in freezing temperatures. These qualities made them ideal for use in rifles, watches, marine chronometers and many other military instruments and machines.

A Whale-Oiled Machine

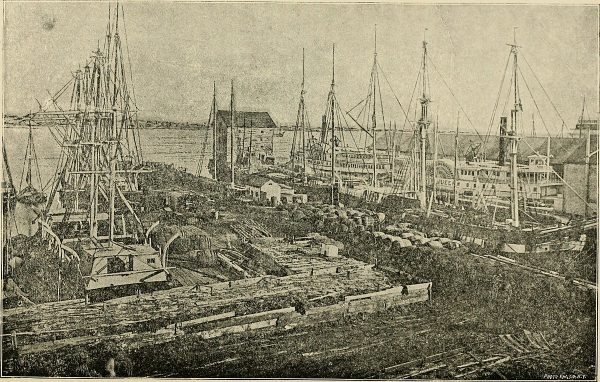

In the 1800s, whaling was a vast and brutal industry–sometimes as deadly for the sailors involved as it was for the whales. And the global epicenter of whaling could be found in New Bedford, MA. All this slaughter wasn’t to feed hungry people with whale meat. It was about all the things people could make out of whale blubber, including soap and of course: lantern fuel. It burned bright and smoke-free.

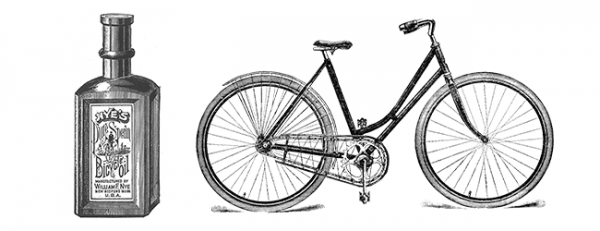

Whale oil rendered in landed in New Bedford was sold to light street lamps, homes and businesses all over the world. The city even adopted the Latin motto Lucem diffundo which means “I spread light”. The phrase can still be seen stamped on the sidewalks outside of city hall. And then, too, there were all of the ways oil could be used as a lubricant, including but not limited to use on: bicycles, bolts, cameras, carriages, cash registers, tapped hands, chisels clippers, cutlery, doors, dentists’ tools, fans, firearms floors, fishing reels, flutes, furniture, golf clubs, harnesses, horses, hoofs, freezers, and locks.

In the 1800’s, whaling transformed New Bedford from a sleepy fishing town into one of the wealthiest cities in the world. Fruitful whaling voyages built vast fortunes for the merchants and financiers that ran the industry. Society men and women strutted through town sporting the latest trends in European fashion. And colorful Victorian mansions sprang up by the dozens. All built with that sweet sweet whale money.

The whaling industry pulled in anyone looking to make a quick buck. And one of those people was a local, New Bedford businessman named William F. Nye. Nye was something of a serial entrepreneur. He had dabbled in everything from selling fruit to building church organs. And, like just about everyone in town, he looked to whales for his next big score. Nye realized there were already plenty of people hawking New Bedford whale oil for lamps and soap. Those markets were saturated. But in 1865, he found a new way to sell whales to the world.

For most of history, machines were lubricated with whatever local material was lying around — animal fat, vegetable oil, sometimes just water or mud. But the industrial revolution brought an explosion of new kinds of machinery. Factories sprung up, brimming with steam engines and spinning machines and looms. Everything newer, bigger, and faster…and in need of lubrication. And suddenly, whatever peanut oil was lying around was no longer good enough to keep the modern mechanical world moving at top speed. The 1800s saw a wave of patents for new kinds of lubricant. These were not materials just plucked out of nature, but refined and mixed together. There were blends of graphite and lard, olive oil with rock dust.

It was a world full of friction. Scientists and engineers were racing to design quality lubrication for it. And William F. Nye realized there was something special about the oil from those giant marine mammals landing in the port of New Bedford. by the half-million. Among other things, whale blubber stays slippery and it doesn’t congeal in the cold like other oils. Whale oil is also non-corrosive. It doesn’t wear down metals. A vital quality given the proliferation of metal machinery at the time. Oil from sperm whales was a particularly good all-temperature lubricant — and sperm whales live everywhere from the equator all the way to the edge of the sea ice in both the Arctic and Antarctic.

Many of his first customers were whalers themselves. He sold the refined oil from sperm whales and some other species as a lubricant for timepieces, including chronometers. Those machines helped ships navigate at sea, often for years on end. Nye’s business grew, and he moved his refining operation from his kitchen, into a store front and eventually into an entire factory where he could make lubrication for all the new fangled machines coming to the American home.

Nye wasn’t the only one refining whale oil into lubricant. But it was Nye who had the idea to specialize — to engineer a unique refining process for each application of lubricant. He made a super-fine lubricant just for music boxes. And thicker one just for firearms. For every machine, he had a lubricant. Nye led the charge of oil refiners who applied the principles of chemistry, physics and engineering to the problem of friction.

By 1900, Nye had started experimenting with lubricant from different sources, like olive oil and neat’s-foot oil made from cattle bones. His specialty, though, remained his high-end whale oil, which he was shipping to eager customers all over the world. Nye had accomplished what he set out to do: open up a whole new market for whale-based products, and make a lot of money doing it. But the early decades of the 20th century brought what we know today as: supply chain issues.

Through decades of overfishing, New Bedford’s whalers had harpooned themselves in the foot. Whales grew scarce. And ships had to chase their remaining prey further and further out to sea. The last whaling ship from New Bedford Harbor sailed in 1927. The city’s once-colorful mansions fell into drab disrepair. And Nye’s supply of raw materials largely dried up. The market for lubricants was taken over by cheaper, petroleum-based products.

Petroleum products were terrible for the climate and toxic to people living near refineries. But as lubricants, they had a lot going for them. They were cheap and they could be mass-produced by oil companies. And they didn’t require death-defying years-long voyages in pursuit of an elusive white whale.: But just because oil companies could make lubricants on a massive scale, doesn’t mean those lubricants worked perfectly. In 1966, a British engineer named Peter Jost published a paper that would become the constitution for the small-but-growing field of research he dubbed: tribology. The study of friction, wear, and lubrication. It found that unnecessary wear and tear on machinery–caused by bad lubrication–was dragging down the nation’s productivity by more than 1 percent of GDP, the equivalent of billions of dollars.

Around the time of the Jost report, Nye’s few remaining employees began tinkering with a new type of lubricant. Not whale oil, not petroleum, but synthetic lubricant–made with new kinds of chemicals cooked up in the lab. Synthetics meant the company could turbocharge their designing of specialty lubricants for particular applications. Because now there were so many different chemicals to try out.

As the computer era dawned, Nye spent the late 20th century crafting custom lubricants that were just right for keeping keyboards clacking, printers printing, and hard drives spinning at thousands of rotations per minute. With a focus on synthetics, the company built itself back up. Today they make more than 1000 different lubricants, each designed to enable the most important technologies of our time. Including the Perseverance Rover currently exploring the surface of Mars — not to mention Xbox controllers.

Good grease doesn’t happen by accident. It’s taken centuries of careful design and development to keep our machines running, from the seafaring age to the digital age. Even though William Nye was chasing a fad when he got into the whale business, he stumbled upon selling a solution to a problem that would need solving until the end of time. |