It's a lot more complicated than you think.

Maybe Zoe Phinn should submit a paper to the science journal Nature.

Eric

These Scientists Say Cosmic Ray Radiation Has an Effect on Climate Change

Environment20 December 2017

By David Nield

(Dominik Schröder/Unsplash)

Cloud formation depends on a number of factors, including atmospheric temperature and the amount of water vapour in the air, but we might be able to add another influence to the mix: cosmic rays beaming down through space.

New research suggests these rays are capable of seeding clouds with their radiation bursts, affecting weather conditions and even climate change in the long term.

Scientists from the Technical University of Denmark (the Danmarks Tekniske Universitet or DTU) suggest that their experiments show varying radiation from the Sun and other supernovae could lead to variations on our weather - but not everyone is convinced.

Artist's impression of cosmic rays hitting the atmosphere. (H. Svensmark/DTU)

"Finally we have the last piece of the puzzle explaining how particles from space affect climate on Earth," says lead researcher Henrik Svensmark.

"It gives an understanding of how changes caused by Solar activity or by supernova activity can change climate."

The clouds in our skies develop from cloud condensation nuclei: that is, water vapour condensing on what are called aerosols - such as small bits of dust, ice, and salt in the atmosphere. This happens when the amount of water vapour and temperature conditions are just right.

Then we have the cosmic rays, high energy radiation made from protons and the nuclei of elements including hydrogen and helium. These rays barrel through our entire Universe, ejected by the Sun and other stellar objects.

We know that when cosmic rays hit Earth's atmosphere, they produce a shower of electrically charged "secondary" particles or ions.

What Svensmark and his colleagues are proposing is that these ions add extra material to the aerosols, ultimately forming bigger clouds, and impacting cloud cover and the temperature at ground level.

To test this, they rigged up a test chamber that was 8 cubic meters (about 283 cubic feet) in size. They were able to get more small clouds to form from aerosols when passing electrically charged particles through the chamber.

The researchers also produced computer models to back up their hypothesis that extra cosmic ray activity could produce more low clouds, eventually cooling Earth's surface.

Based on their experiments and modelling, the team estimates that between 5-50 percent of aerosol growth rate could be down to ions – that's based on two years of testing in the chamber with over 3,100 hours' worth of data samples in total.

Big shifts in cosmic ray activity, like exploding supernovae, could even cause enough of a difference to shift the temperature on our planet, the team suggests.

However, the researchers themselves do admit that parts of their hypothesis are "speculative" – there are a lot of factors at play in cloud formation, and it's impossible for a cloud chamber in a lab to properly model the Earth's atmosphere.

While the findings suggest that cosmic rays could play at least some part in cloud formation, claims about effects on climate change must be weighed up against the evidence we have for the effect of greenhouse gases and other factors down here on the planet.

"Of itself, this is an interesting and plausible result, and if it stands up to more detailed scrutiny it may prove an important contribution to aerosol microphysics," says atmospheric scientist Hamish Gordon, from the University of Leeds in the UK.

"However, it is very far from 'the last piece of the puzzle explaining how particles from space affect climate on Earth'."

Recent research carried out at CERN by Gordon and others suggests that particles released by human beings and trees are likely to be much more influential in terms of affecting cloud cover than showers of particles from space.

"In the climate of the last few thousand years, [cosmic rays] can make no appreciable difference to overall cloud-seeding particle concentrations in the atmosphere or to temperature," Gordon told Ryan F. Mandelbaum at Gizmodo.

Whatever's happening above our heads – and we're still only part of the way through understanding it all – the idea that cosmic ray activity can add to the build up of clouds is going to be worth investigating in the future.

"The theory of ion-induced condensation should be incorporated into global aerosol models, to fully test the atmospheric implications," conclude the researchers.

The findings have been published in Nature Communications.

sciencealert.com

Then there is the total power output of the Sun striking the top of our atmosphere.

Four Decades and Counting: New NASA Instrument Continues Measuring Solar Energy Input to Earth

NASA

Katy Mersmann

Nov 28, 2017

Article

We live on a solar-powered planet. As we wake up in the morning, the Sun peeks over the horizon to shed light on us, blanket us with warmth and provide cues to start our day. At the same time, our Sun’s energy drives our planet’s ocean currents, seasons, weather and climate. Without the Sun, life on Earth would not exist.

For nearly 40 years, NASA has been measuring how much sunshine powers our home planet. This December, NASA is launching an instrument to the International Space Station to continue monitoring the Sun’s energy input to the Earth system. The Total and Spectral solar Irradiance Sensor (TSIS-1) will precisely measure what scientists call “total solar irradiance.” These data will give us a better understanding of Earth’s primary energy supply and help improve models simulating Earth’s climate.

“You can look at the Earth and Sun connection as a simple energy balance. If you have more energy absorbed by the Earth than leaving it, its temperature increases and vice versa,” said Peter Pilewskie, TSIS-1 lead scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric Physics (LASP) in Boulder, Colorado. Under NASA’s direction, LASP is providing and distributing the instrument’s measurements to the scientific community. “We’re measuring all the radiant energy that is coming to Earth.”

In terms of climate change research, scientists need to understand the balance between energy coming in from the Sun and energy radiating out from Earth, as modulated by Earth’s surface and atmosphere. Measurements from TSIS, the Total and Spectral Solar Irradiance Sensor, will help our understanding of the Earth-Sun connection and improve climate models.

NASA Measures All the Sun’s Energy to Earth

NASA Goddard

1.56M subscribers

In terms of climate change research, scientists need to understand the balance between energy coming in from the Sun and energy radiating out from Earth. In December 2017, NASA is launching a new instrument to measure half of that equation – the total amount of Sun’s energy input to Earth, known as total solar irradiance. Scientists will use NASA's Total Solar and Spectral Irradiance Sensor (TSIS-1) to measure to quantify variations in the sun’s total amount of energy and help improve models simulating Earth’s climate.

youtube.com

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Michael Starobin

But it’s not so simple: the Sun’s output energy is not constant. Over the course of about 11 years, our Sun cycles from a relatively quiet state to a peak in intense solar activity — like explosions of light and solar material — called a solar maximum. In subsequent years the Sun returns to a quiet state and the cycle starts over again. The Sun has fewer sunspots — dark areas that are often the source of increased solar activity — and stops producing so many explosions, going through a period called the solar minimum. Over the course of one solar cycle (one 11-year period), the Sun’s emitted energy varies on average at about 0.1 percent. That may not sound like a lot, but the Sun emits a large amount of energy – 1,361 watts per square meter. Even fluctuations at just a tenth of a percent can affect Earth.

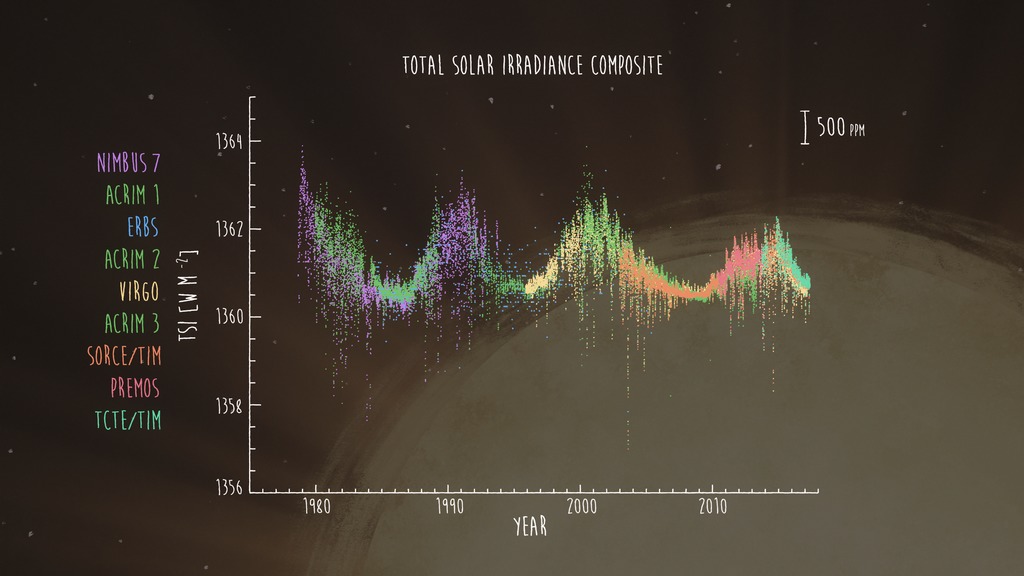

This composite shows the Sun’s total solar irradiance since 1978 as observed from nine previous satellites. These observations are important to help scientists know precisely how much the Sun’s energy changes and how that affects Earth.

Credits: NASA

In addition to those 11-year changes, entire solar cycles can vary from decade to decade. Scientists have observed unusually quiet magnetic activity from the Sun for the past two decades with previous satellites. During the last prolonged solar minimum in 2008-2009, our Sun was as quiet it has been observed since 1978. Scientists expect the Sun to enter a solar minimum within the next three years, and TSIS-1 will be primed to take measurements of the next minimum.

“We don’t know what the next solar cycle is going to bring, but we’ve had a couple of solar cycles that have been weaker than we’ve had in quite a while so who knows. It’s a pretty exciting time to be studying the Sun,” said Dong Wu, the TSIS-1 project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Goddard is responsible for the overall development and operation of TSIS-1 on the International Space Station.

TSIS-1 data are particularly important for helping scientists understand the causes of total solar irradiance fluctuations and how they are connected with the Sun’s behavior over decades or centuries. Today, scientists have neither enough data nor the forecasting skill to predict whether total solar irradiance has any long-term trend, said Doug Rabin, deputy project scientist at Goddard. TSIS-1 will continue a data sequence that is vital to answering that question.

The Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE), launched in 2003, currently measuring total solar irradiance from space, observed a dip in the irradiance during intense solar flare activity in September 2017. TSIS-1 will continue these observations with one-third the uncertainty of its predecessor.

Credits: NASA

These data are also important for understanding Earth’s climate through models. Scientists use computer models to interpret changes in the Sun’s energy input. If less solar energy is available, scientists can gauge how that will affect Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, weather and seasons by using computer simulations. The input from the Sun is just one of many factors scientists used to model Earth’s climate. Earth’s climate is also affected by other factors such as greenhouse gases, clouds scattering light and small particles in the atmosphere called aerosols — all of which are taken into account in comprehensive climate models.

TSIS-1 will study the total amount of solar radiation emitted by the Sun using the Total Irradiance Monitor, one of two sensors on the instrument. The second sensor, called the Spectral Irradiance Monitor, will measure how the Sun’s energy is distributed over the ultraviolet, visible and infrared regions of light. TSIS-1 spectral irradiance measurements of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation are critical to understanding the ozone layer — Earth’s natural sunscreen that protects life from harmful radiation.

“Knowing the Sun’s behavior and knowing how Earth’s atmosphere responds to the Sun is even more important now because of all the different factors that affect climate change. We need to understand how all of these interact on Earth’s system,” said Pilewskie.

For more information, visit:

By Kasha Patel

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

nasa.gov |