Accessibility statement Skip to main content

Democracy Dies in Darkness

Sign in

United States

United Kingdom

1990200020102023CoalWind & solarGasOther

Climate Lab

This country ditched coal. Here’s what the world can learn from it.

Analysis by Niko Kommenda

and

Harry Stevens

October 4, 2024 at 7:05 a.m. EDT

The last operating coal power plant in Britain closedthis week, ending more than 140 years of coal-fired electricity and proving that major economies can wean themselves off the dirtiest fossil fuel.

“It’s a massive movement,” said Dave Jones, an electricity analyst at Ember, a London-based think tank. “The fact that the first country in the world to have a coal power plant, to lean so heavily into coal starting the industrial revolution, is now out of coal is extremely symbolic.”

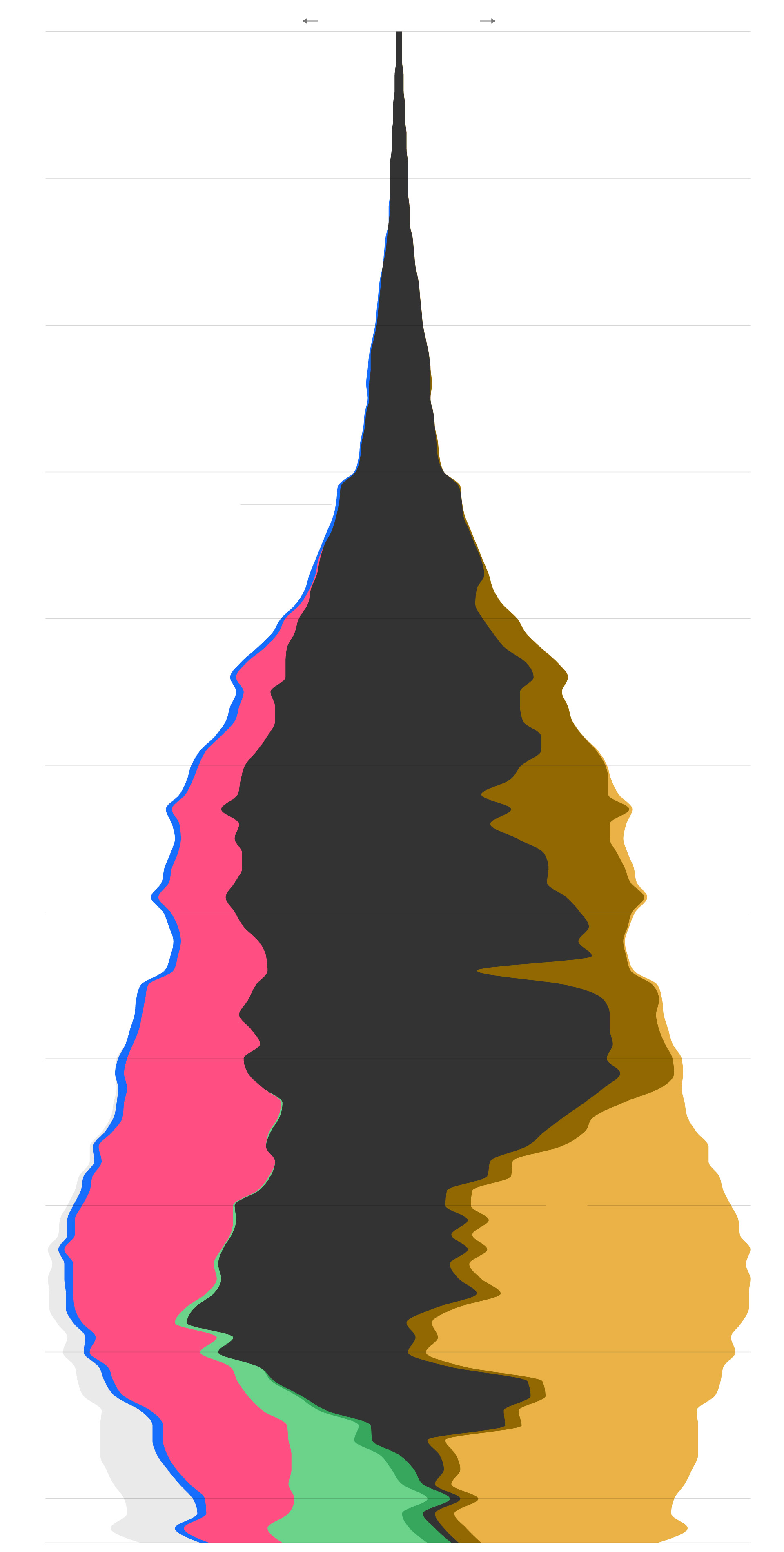

streamgraph of uk power generation over time

U.K. power generation by source

1920

Coal power

Nearly 100 years ago, Britain passes a law to set up the first national power grid in the world

1930

1940

Having been used for heating for hundreds of years, coal becomes the backbone of the country’s growing power sector

1950

Hydropower

Hydropower never plays a significant role in Britain’s power mix

1960

1960s

More than 170 coal power plants are in operation across Britain

1970

Oil

1980

1984

About three quarters of coal miners go on strike, leading to a temporary drop in coal-fired generation

1990

1991

Peak of coal power in Britain

Nuclear

Unlike in countries like France, nuclear never becomes the dominant power source in Britain

Gas

2000

Gas from the North Sea emerges as a cheaper and cleaner alternative to coal

2005

The E.U., which includes Britain at the time, introduces a carbon price for power producers

2010

2013

Britain introduces an additional carbon tax for power producers

Other

2014

Subsidies for renewables guarantee developers a steady stream of revenue

Wind

Solar

2020

2023

Long before global warming emerged as an issue, experts had proved that burning coal posed environmental and health threats. Coal plants pollute the air, cause acid rain and contaminate the soil and water with mercury. In Britain, the London Great Smog of 1952 probably killed as many as 12,000 people and prompted a government crackdown on the widespread use of coal for household heating.

In the 20th century, as trains, ships, stoves and other machines switched to oil and gas, coal retained its central role in running the turbines that power plants use to generate electricity. In recent decades, efforts to turn off coal-fired power plants have accelerated given their outsize contribution to global warming.

Although Britain still uses coal for steel manufacturing, which accounts for 2 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, experts say the country’s transition from coal-fueled electricity offers lessons to other countries seeking to phase it out.

Joel Jaeger, a climate and energy research at the World Resources Institute, said Britain’s transition from coal is “truly historic” and “proves that other countries can also achieve rapid speeds of coal reduction.”

Few economically developed countries have completely phased out coal. Most that have, such as Iceland, Switzerland, Sweden and Norway, have little need for coal because they generate plenty of power with an older generation of carbon-free technologies: hydroelectric dams, nuclear power plants and geothermal reservoirs.

Britain is one of the first countries, and the largest, to phase out coal by relying heavily on wind and solar. Portugal also did so, but it is smaller and less heavily industrialized. Germany has tried, but it still produces about a quarter of its power with coal and does not plan to complete its phaseout until 2038.

United Kingdom

Power generation by source, in terawatt-hours

19902000201020230100200300400CoalGasOtherWind & solar

Portugal1990200020102023015304560

Germany19902000201020230175350525700

Germany’s clean-energy transition has been slower because it has few hydroelectric dams, and it shut down all of its nuclear plants, which together generated 30 percent of the country’s electricity in 2000. Britain gets about 15 percent of its electricity from nuclear plants, while Portugal makes about a quarter of its power with hydroelectricity.

Although market forces — first competition from cheap natural gas and later from cheaper renewables — helped Britain phase out coal, experts say government policy played a major part.

“The United Kingdom demonstrated that with the right policies, it’s possible to transition away from coal power while maintaining the reliability of the electricity system,” said Jennifer Morris, a principal research scientist at the MIT Energy Initiative.

Story continues below advertisement

Advertisement

The European Union created a cap-and-trade regime in 2005, when Britain was still a member, but that policy was not very effective because the price of carbon was too low, Morris said. But in 2013, the country set a higher carbon price, forcing many coal plants to close.

Even as political power shifted between the Labour and Conservative parties, Britain pressed ahead with policies to promote clean energy. It set legally binding greenhouse gas emissions targets, regulated air pollution, and encouraged the expansion of renewable energy by introducing a system to ensure wind and solar developers could sell power at a stable, profitable price.

The transition away from coal has been slower in the United States than in Britain. Although the United States has adopted some similar policies, including pollution controls and incentives for renewable developers, U.S. policy has fluctuated more dramatically as party control of Congress and the White House has alternated between Republicans and Democrats.

For instance, an Environmental Protection Agency rule finalized in April requires coal plants expected to operate past 2039 to reduce their emissions by 90 percent by 2032. But it faces legal challenges, and Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump has vowed to overturn it if elected.

Although a quarter of U.S. coal capacity is set to retire by 2029, “it will take dedicated policies to phase out the remaining coal plants,” Morris said. She recommended a carbon tax, which lawmakers have consistently rejected, or an emissions cap such as the EPA rule.

Among the world’s advanced economies, South Korea and Japan have made the slowest progress on replacing coal. These countries have less land available for wind and solar farms, and have fewer natural-gas reserves.

United States

Power generation by source, in terawatt-hours

199020002010202301,2502,5003,7505,000Wind & solarCoalGasOtherWind & solar

Japan199020002010202305001,0001,5002,000

South Korea19902000201020230175350525700

Japan’s clean-energy transition was also hampered in 2011 by the Fukushima meltdown, after which the country scaled back nuclear generation.

Developing countries such as China and India have no prospect of abandoning coal anytime soon. China is installing renewable power faster than any other country in the world, but coal generation is also necessary to fuel the country’s rapid development.

Last year’s United Nations climate change negotiations in Dubai stalled over resistance from China and India to committing to phasing out fossil fuels. The conference finally adopted a plan to phase “down” fossil fuels.

China

Power generation by source, in terawatt-hours

199020002010202302,5005,0007,50010,000GasWind & solarCoalGasOtherWind & solar

India199020002010202305001,0001,5002,000

Indonesia19902000201020230100200300400

Even after coal is gone from the electricity mix, countries will be confronted with the next phase of the clean-energy transition: completely decarbonizing the power sector.

“The environmental community has been pretty focused on coal because it is the most polluting fossil fuel and because it is low-hanging fruit,” Jaeger said. “I think it’s going to be harder than the coal transition.”

Renewables are fueled by blowing wind and shining sun, which are not always available. Beyond some share of power generation — 80 percent or so, Jaeger said — renewables must be backed up by dependable supplies that don’t emit greenhouse gases, which rules out natural gas.

Story continues below advertisement

Advertisement

Grid-scale batteries have become cheaper but can still provide only about eight hours of backup power. The U.S. and British governments have shown revived interest in nuclear power, but both countries have struggled in recent decades to build plants quickly and cheaply.

Meanwhile, as electric vehicles and heat pumps become more common and power-hungry technologies such as artificial intelligence grow, Britain, the United States and others will be trying to make this daunting energy transition just as electricity demand is rising.

Check our work

The data shown in the charts in this article are from Our World in Data, which provides 1920-2023 for the U.K. and shorter time periods for other countries. The code to produce simple versions of the stacked area charts can be found in this computational notebook. To get in touch, email Niko, Harry or our editor, Monica Ulmanu.

Comments

Niko KommendaNiko Kommenda is a graphics reporter on The Washington Post's climate and environment team. Before joining The Post, he worked as a visual journalist at the Financial Times and the Guardian. @niko_tinius

Follow

Harry StevensHarry Stevens is the Climate Lab columnist at The Washington Post. He was part of a team at The Post that won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting for the series “2C: Beyond the Limit.” @Harry_Stevens

Follow

Subscribe to comment and get the full experience. Choose your plan ?

Most Read

1

Carolyn Hax chat: She got dressed up, but her mother said she looked ‘awful’

2

The reasons people say they leave Donald Trump’s rallies early

3

No, Biden didn’t take FEMA relief money to use on migrants — but Trump did

4

As Trump makes false claims about hurricane relief, White House calls it ‘poison’

5

The female soldiers who predicted Oct. 7 say they are still being silenced

Company

About The Post Newsroom Policies & Standards Diversity & Inclusion Careers Media & Community Relations WP Creative Group Accessibility Statement Sitemap

Get The Post

Become a Subscriber Gift Subscriptions Mobile & Apps Newsletters & Alerts Washington Post Live Reprints & Permissions Post Store Books & E-Books Today’s Paper Public Notices

Contact Us

Contact the Newsroom Contact Customer Care Contact the Opinions Team Advertise Licensing & Syndication Request a Correction Send a News Tip Report a Vulnerability

Terms of Use

Digital Products Terms of Sale Print Products Terms of Sale Terms of Service Privacy Policy Cookie Settings Submissions & Discussion Policy RSS Terms of Service Ad Choices

washingtonpost.com © 1996-2024 The Washington Post

|