Re <<F*CKING F*CKS>> really f*cked up ‘ugely, sideways, and hard, then dropped off at street corner together with some bubble gum like so much cat food, all for being too-greedy and for filled with so much bad-water

bloomberg.com

A Naked Short on Gold in a Country That Loves Glitter

India’s plan to wean its population off the yellow metal has left New Delhi nursing a $13 billion liability.

20 March 2025 at 22:00 CET

By Andy Mukherjee

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services in Asia. Previously, he worked for Reuters, the Straits Times and Bloomberg News.

A naked short on gold in a country that loves glitter has left India nursing a $13 billion liability.

Photographer: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg

Back in 2015, India’s finance ministry had a clever idea: Why not borrow cheaply by promising returns linked to bling? In the process, the officials would wean the country off a costly addiction. Indians would be able to satiate their world-beating appetite for gold by punting on something even more glittering.

That something, the mandarins reckoned, could only be a government-backed investment option that allowed investors to earn some cash while speculating on the price of their best-loved commodity — without actually having to buy it.

But the officials forgot a cardinal rule. If a trade looks too good to be true, it probably is.

As it’s becoming painfully evident now, India’s 10-year-old sovereign gold bond program is just a $13 billion naked short position for the government, an albatross around its neck at a time when bullion prices have gone parabolic and show no sign of subsiding. It’s the taxpayers who are on the hook for paying that money to bondholders.

This wasn’t how the program was supposed to run. The special debt, it was decided, would pay a 2.75% coupon (reduced later to 2.5%), and the investment itself would be measured in grams of gold. Upon redemption eight years later, investors would be given the prevailing market value of the metal in rupee terms.

At least on paper, it all made sense. With the euro zone back from the brink of a messy breakup, the demand for safe havens was on its way down globally. Suppose someone bought 1 gram worth of the metal-linked bonds in November 2015 for a little over 2,500 rupees, which came to about $38 in those days. Even if New Delhi had to redeem the notes for 50% more — 3,750 rupees -- the borrowing cost would still be less than the near-8% yield on regular government debt.

There were other advantages. To the extent people would be drawn to the financial product, they would be less keen to buy the physical asset, saving India some of the $30 billion in hard currency that it had spent annually over the previous decade on imports of the precious metal.

However, nearly every one of those assumption came a cropper. First, international prices zoomed — from just about $1,500 an ounce in late 2019 to $3,000 now. The very first bond matured at more than double its issue price, making it a costly form of borrowing. Two, the popular craze for bullion never really went away even as it became more expensive. Average annual imports have stood at $37 billion over the past 10 years. To nip this demand, New Delhi raised customs duties to 15% in 2022.

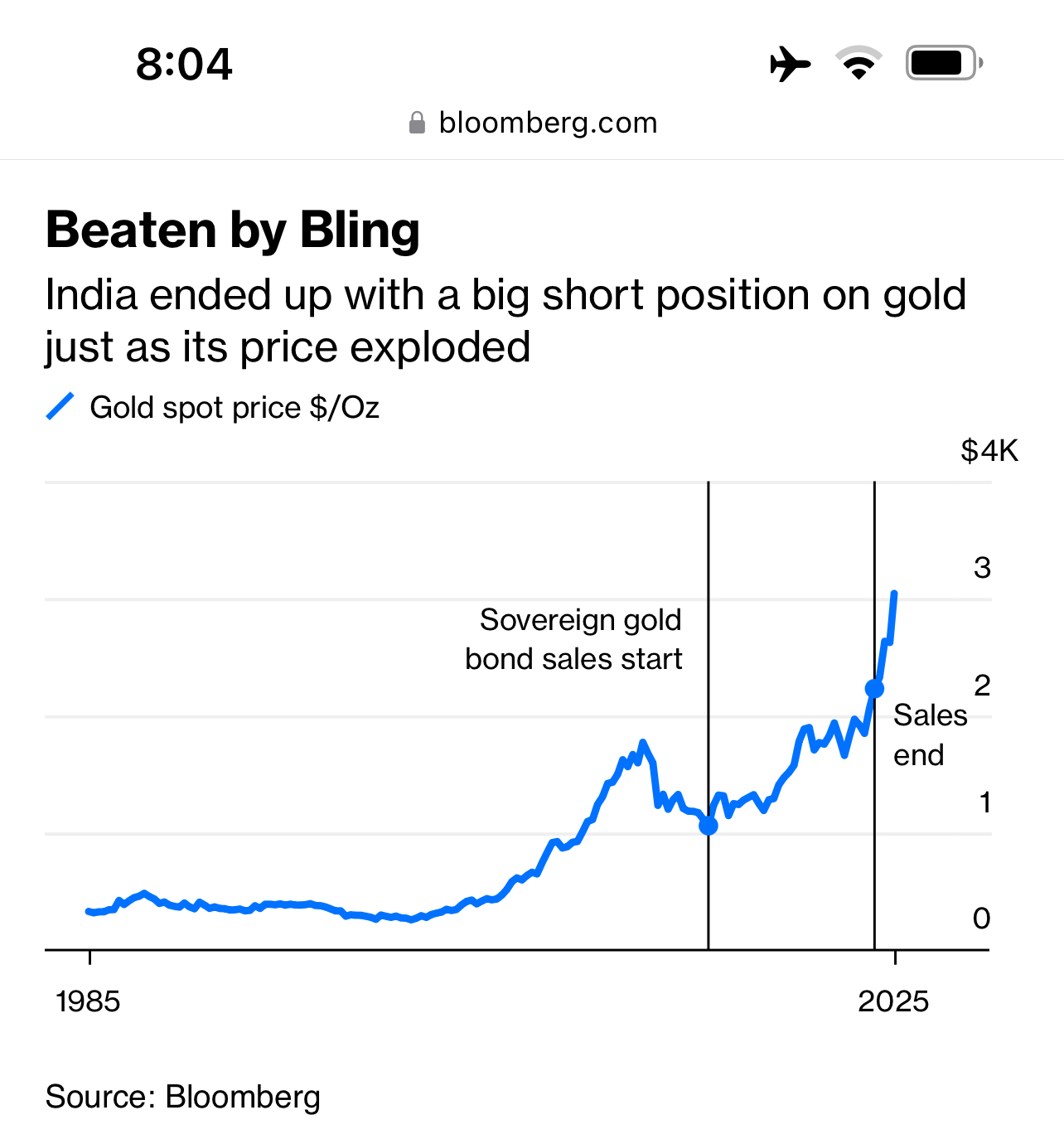

Beaten by Bling

India ended up with a big short position on gold just as its price exploded

Source: Bloomberg

That little maneuver also backfired. It boosted the domestic price, further ballooning the government’s outgo on maturing bonds. New Delhi panicked. Last year, it slashed import tariffs to 6%.

But that was before the US elections in November. With Donald Trump in the White House, the value of the world’s preferred inflation hedge is going through the roof amid fears of what his tariffs would do to consumer prices. This week, a bond sold in March 2017 was redeemed for more than 8,600 rupees, or three times the issue price of the 1 gram note. Investors “have hit a jackpot,” the Economic Times noted.

Taxpayers have come up snake eyes, though. Do the math. The government sold bonds worth 147 tons in 67 tranches. As of last month, New Delhi was still on the hook for 132 tons, which translates to a liability of 1.2 trillion rupees ($13 billion) at current prices. The last bond will only retire in February 2032. Who knows what the commodity will cost seven years from now.

If the current frenzy in market prices proves durable, large losses are almost guaranteed. Some analysts have noted that the central bank’s gold — 879 tons last month — offers a natural hedge. But the Reserve Bank of India has acquired those quantities to diversify the base of safe assets backing its liabilities: the domestic money supply. They were never meant to backstop the government’s borrowing.

Already, the share of the precious metal in the RBI’s foreign-exchange reserves has risen to 11.5%, the highest on record, according to the World Gold Council. If the market gets the sense that they are being amassed to pay off creditors in the future, it will raise difficult questions about the institution’s independence.

The whole thing is an avoidable mess. India has thrown in the towel, and discontinued fresh issuances of the bonds. But that was only after it took in 270 billion rupees during the fiscal year that ended last March, the most in the program’s truncated history.

Indians’ love of the yellow metal is coded in their DNA, for reasons that have as much to do with culture as economic security. For many families, especially in rural areas, it is the only asset they can pledge in a pinch. Adding to the sheen, it’s the country’s best-performing investment so far this year, a cushion against brutal losses in the stock market. It was valiant of the government to try to tamp the popular impulse for hoarding gold, but reckless of it to mount an unhedged bet against a basic instinct. |