Revolution in medicine: A molecule produced by gut bacteria causes atherosclerosis, responsible for millions of deathsThe discovery, made thanks to an experiment involving hundreds of bank employees in Spain, opens the door to new treatments beyond reducing cholesterol

A volunteer during a medical trial at the National Center for Cardiovascular Research in Madrid.CNIC A volunteer during a medical trial at the National Center for Cardiovascular Research in Madrid.CNIC

Manuel Ansede

Madrid - JUL 17, 2025 - 04:50 EDT

A team of Spanish scientists made a striking announcement 15 years ago: they were seeking thousands of volunteers among the employees of Banco Santander in Madrid: researchers wanted to study them in depth for decades, in order to understand the onset of cardiovascular disease in healthy people. The results are even more surprising. Researchers have discovered that gut bacteria produce a molecule that not only induces but also causes atherosclerosis, the accumulation of fat and cholesterol in the arteries that can lead to heart attacks and strokes. This unexpected link between microbes and cardiovascular disease — the leading cause of death in humanity — is a paradigm shift. The work was published Wednesday in the journal Nature, a showcase for the world’s best science.

The in-depth study of Santander employees using advanced medical imaging equipment soon revealed another shocking finding: atherosclerosis was ubiquitous. The volunteers were apparently healthy, aged between 40 and 55, but 63% of the participants showed signs of the disease. The new results show that some gut bacteria, in certain states, produce imidazole propionate, a simple molecule with six carbon atoms, eight hydrogen atoms, two nitrogen atoms, and two oxygen atoms (C6H8N2O2). This compound enters the blood, interacts with immature white blood cells, and triggers an inflammatory reaction in the arteries, which promotes the buildup of fatty plaques.

“Imidazole propionate induces atherosclerosis on its own. There’s a causal relationship,” asserts the biologist David Sancho, 53, leader of the new study at the National Center for Cardiovascular Research (CNIC) in Madrid. His team administered the molecule to mice, which developed the disease. Furthermore, scientists observed elevated levels of imidazole propionate in one out of every five volunteers with active atherosclerosis, the type in which fatty plaques are more likely to rupture and form the blood clots that cause heart attacks and strokes. The new results demonstrate that atherosclerosis is not only a disease caused by fat, but that it also has an inflammatory and autoimmune component, according to Sancho.

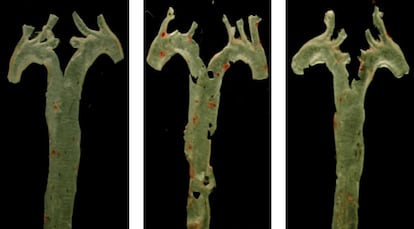

Aorta arteries from a healthy mouse (left), another exposed to imidazole propionate (center), and another treated with propionate and an inhibitor drug, with red staining of atherosclerotic plaque.CNICThe good news is that if C6H8N2O2 causes the problem in a significant percentage of patients, steps can be taken to prevent it. Researchers have identified the receptor to which the molecule binds and have managed to block it with a drug, reducing the progression of atherosclerosis in mice fed a high-cholesterol diet. “With this inhibitor, we completely prevented the development of the disease,” says Sancho, who has patented the experimental treatment with other co-authors, such as the Italian pharmacologist Annalaura Mastrangelo, their colleague Iñaki Robles, and the cardiologist Valentín Fuster, director general of the CNIC in Madrid and president of the Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital in New York, which has borne his name for two years. Aorta arteries from a healthy mouse (left), another exposed to imidazole propionate (center), and another treated with propionate and an inhibitor drug, with red staining of atherosclerotic plaque.CNICThe good news is that if C6H8N2O2 causes the problem in a significant percentage of patients, steps can be taken to prevent it. Researchers have identified the receptor to which the molecule binds and have managed to block it with a drug, reducing the progression of atherosclerosis in mice fed a high-cholesterol diet. “With this inhibitor, we completely prevented the development of the disease,” says Sancho, who has patented the experimental treatment with other co-authors, such as the Italian pharmacologist Annalaura Mastrangelo, their colleague Iñaki Robles, and the cardiologist Valentín Fuster, director general of the CNIC in Madrid and president of the Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital in New York, which has borne his name for two years.

Another of the study’s authors, the Swedish biologist Fredrik Bäckhed, had already discovered in 2018 that imidazole propionate levels were higher in people with type 2 diabetes. And just three months ago, independent research led by the cardiologist Arash Haghikia advanced the link between the bacterial molecule and atherosclerosis. “The fact that two different groups came to the same conclusion strengthens our confidence that this is a significant and relevant discovery,” argues Haghikia, of Ruhr University Bochum (Germany). “What is particularly striking is that imidazole propionate appears to promote atherosclerosis even when cholesterol levels are normal. This could help explain why some people develop heart disease despite having few or no traditional risk factors, such as high cholesterol or high blood pressure,” he emphasizes.

Left to right: the biologist David Sancho and the pharmacologists Annalaura Mastrangelo and Iñaki Robles, at the National Center for Cardiovascular Research in Madrid.CNICCardiovascular diseases kill 18 million people each year. Banco Santander’s chairman, Emilio Botín, died of a heart attack four years after signing off on the project, which has allowed for the analysis of more than 4,000 volunteer workers, 400 of whom are included in this new study. The research, conducted using expensive and complex techniques such as computed axial tomography (CAT) and positron emission tomography (PET), has made it possible to detect high levels of imidazole propionate in the very early stages of atherosclerosis, which could greatly facilitate diagnosis at that invisible stage when a person is unknowingly at risk. Left to right: the biologist David Sancho and the pharmacologists Annalaura Mastrangelo and Iñaki Robles, at the National Center for Cardiovascular Research in Madrid.CNICCardiovascular diseases kill 18 million people each year. Banco Santander’s chairman, Emilio Botín, died of a heart attack four years after signing off on the project, which has allowed for the analysis of more than 4,000 volunteer workers, 400 of whom are included in this new study. The research, conducted using expensive and complex techniques such as computed axial tomography (CAT) and positron emission tomography (PET), has made it possible to detect high levels of imidazole propionate in the very early stages of atherosclerosis, which could greatly facilitate diagnosis at that invisible stage when a person is unknowingly at risk.

Sancho and his colleagues acknowledge that further research will be needed to identify the specific strains of bacteria capable of producing the molecule, but they point to “changes in intestinal microbial ecology” following dietary modifications, with an increase in bacterial genera such as Escherichia, Shigella, and Eubacterium. When Fuster presented the project in 2010, he noted how difficult it is to diagnose cardiovascular problems early and how simple it is to prevent them, with measures such as exercising, following a healthy diet, and not smoking. The new study shows that blood levels of imidazole propionate are lower in people with diets rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fish, tea, and low-fat dairy products.

The Argentine microbiologist Federico Rey and Indian pathologist Vaibhav Vemuganti applaud the “exciting opportunities” that the new study opens for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. In a commentary also published Wednesday in Nature, the two experts emphasize that exposure to imidazole propionate worsens plaque formation in the arteries of mice. “This effect occurs independently of changes in cholesterol levels, a surprising result given the central role of cholesterol in the development of atherosclerosis,” note the two specialists, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “This discovery offers an interesting clue about a possible new factor involved in the origin of atherosclerosis. This is very relevant because, although lowering cholesterol — through drugs called statins, for example — can effectively reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, a considerable proportion of people still experience adverse cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarctions or strokes,” they warn. The CNIC itself said in a statement that the new study “could revolutionize” the diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis.

Sancho stresses that the work has been made possible thanks to the collaboration of thousands of volunteer employees of Banco Santander in Madrid, but also thanks to grants of €1 million from the “la Caixa” Foundation, €150,000 from the European Research Council and €100,000 from the State Research Agency.

The discovery of the decisive effect of imidazole propionate on atherosclerosis takes place against a backdrop in which the scientific community is revealing the unknown role of intestinal microbes in some human diseases. The biotechnologist Cayetano Pleguezuelos and his colleagues at the Hubrecht Institute (The Netherlands) demonstrated in February 2020 that a strain of the bacterium Escherichia coli produces a toxic molecule, called colibactin, which damages the DNA of human cells and causes malignant tumors.

Cases of colorectal cancer are skyrocketing in people under the age of 50, due to unknown causes, doubling in many countries in the last two decades. Another study, led by computational biologist Marcos Díaz Gay, suggested just three months ago that behind this colorectal cancer epidemic is the Escherichia coli toxin. “In young patients, up to 39 years of age, we see that colibactin pattern in one out of every three cases,” stressed Díaz Gay, of the National Cancer Research Center.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition |