poco, Land Shark, Tench, Rat, koan and Brumar are classic examples of mentally deranged Puritans.

The War on Christmas

April 15, 2025

The War on Christmas begins around the same time each year, when stores start peddling plastic Christmas trees and giant Santa Claus inflatables. Depending on which media talking head is speaking, the war is either a subversive effort by left-wing liberals to erase all traces of Christianity, or a histrionic, right-wing attempt to force religion down every American’s throat. But most people don’t realize Christians battled one another over the holiday centuries before news media kept the War on Christmas in the headlines.

Puritans Cancel Christmas

The Puritans were Protestant English Reformists who gained distinction in the 16th and 17th centuries. After King Henry VIII broke away from the Roman Catholic church and created the Protestant Church of England, Puritans sought to further reform his newly-founded church.

For centuries, people had been celebrating Christmas by going to church, closing businesses, singing carols and enjoying goblets of wassail with family and friends. Since most people of medieval England had little to celebrate, they looked forward to the Christmas season and a break from daily hardships.

The Puritans, however, felt life should be lived solely according to the Bible. In their opinion, the Bible didn’t reference celebrating Christ’s birth at all, let alone recommend drinking and merrymaking; they lobbied to ban Christmas.

In 1642, King Charles I agreed to a request from Parliament to make Christmas a subdued period of fasting and spiritual reflection instead of a boisterous holiday. In January 1645, Parliament produced a Directory for the Public Worship of God, laying out new rules of worship.

Sundays were set aside for worship, but all other church services, festivals and religious revelries—including Christmas—were banned.

Christmas in England is Restored

Parliament didn’t stop there. In 1657, they made it illegal to close businesses on Christmas or attend or hold a Christmas worship service.

But the English people decided they wouldn’t let go of their festivities without a fight. Riots ensued, and many people celebrated Christmas privately in their homes if not their places of worship.

After Oliver Cromwell, a staunch Puritan, ordered the execution of King Charles I and became Lord Protector in 1653, he upheld the ban on Christmas, despite its unpopularity. But when the monarchy was restored in 1660, so was Christmas.

Puritans Ban Christmas in the New World

Some Puritans, unhappy with the Church of England, emigrated to the New World and settled in Massachusetts. They embarked on a hard life shaped by their staunch Christian beliefs and brought along their conviction that Christmas was a holiday for sinners and shouldn’t be observed.

Celebrating Christmas was discouraged but didn’t become a punishable offense until 1659. By 1681, colonial revelers could no longer be fined but were charged with disturbing the peace if caught celebrating in public.

The Puritans managed to force Christmas underground in much of New England, but they couldn’t compel other New World colonies to do the same. Christmas celebrations were commonplace in Virginia, Maryland and other colonies where immigrants brought their holidays traditions intact from the Old World.

Still, the Puritans held Christmas at bay, decade after cheerless decade, until Massachusetts finally made Christmas a legal holiday in 1856—almost 200 years after it was banned. President Ulysses S. Grant made it a federal holiday in 1870.

Black Friday

The enormous popularity of Clement Moore’s 1823 poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas”—with its famous opening lines, “Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house, not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse”—was arguably the catalyst for meshing the religious and secular sides of Christmas.

As Christmas became more popular over the years, it also became more commercialized. Christians and non-Christians alike put up Christmas trees, anticipated visits from Santa Claus and shopped for gifts to buy for family and friends.

And buy they did: To meet the demand, many retailers began hawking their holiday wares before Halloween candy left store shelves.

Black Friday, the Friday after Thanksgiving and official kick-off of the Christmas shopping season, gave way to stores opening their doors on Thanksgiving evening. Not to be left out, online retailers created Cyber Monday to entice online shoppers to buy more.

Buy Nothing Day

Estimates vary, but U.S. consumers are now estimated to spend more than $655 billion annually in holiday retail purchases—$1.3 billion on Christmas trees alone.

But this shopping juggernaut had its detractors: A Vancouver artist, fed up with the mass consumer orgy of Christmas, created Buy Nothing Day, which is also held the Friday after Thanksgiving.

Started in 1992, it encourages people to skip the Black Friday madness, put away their credit cards and not fall prey to Christmas consumerism and overconsumption in general.

The Modern-Day War on Christmas

Despite the commercialization of Christmas, it was still considered mainly a religious holiday for much of the 20th century. Over the last decade or so, secularists, humanists and atheists became more vocal about the separation of church and state.

Multiple lawsuits were filed by private citizens, the ACLU, and other organizations against federal and local governments to remove nativities and other Christian symbols from public places. Legal action has also been taken to remove Christian references, songs and the word “Christmas” from school plays and programs.

Many Christians, however, consider this an attack on their freedom of speech and religious freedom. They assert America was founded on Christian principles and Christmas is a federal holiday celebrating the birth of Christ, so Christian Christmas displays should be left alone no matter where they reside.

Cable News Highlights War on Christmas

When some popular retailers stopped using the word Christmas in their promotional materials and supposedly instructed their employees to avoid saying, “Merry Christmas,” it lit a fire under many Christians.

It also fired-up several cable news hosts such as Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity, both of whom many believe took charge of the modern-day War on Christmas and made it a grass-roots campaign. As word got out, hordes of Christians signed petitions and boycotted the stores, forcing some to change their stance. Other stores continued to use general terms to refer to December 25.

When conservative Pat Buchanan called the secularization of Christmas a hate crime and pastor Jerry Falwell accused leftists of wanting to create a godless America, many liberals claimed the War on Christmas was rubbish. They claimed no one was taking away Christians’ right to celebrate, however, they drew the line at religious public displays.

Proponents on both sides of the debate got plenty of air time, keeping the war in the headlines year after year. The rhetoric amped-up in July 2017 when President Donald Trump announced during a speech at the Celebrate Freedom Concert, “…I remind you that we’re going to start saying ‘Merry Christmas’ again.”

The Puritans are still with us...

NEW ENGLAND HISTORY

How the Puritans Banned Christmas

In 1659 the Puritans banned Christmas in Massachusetts. But why?

Heather Tourgee

December 8, 2021

“The “The

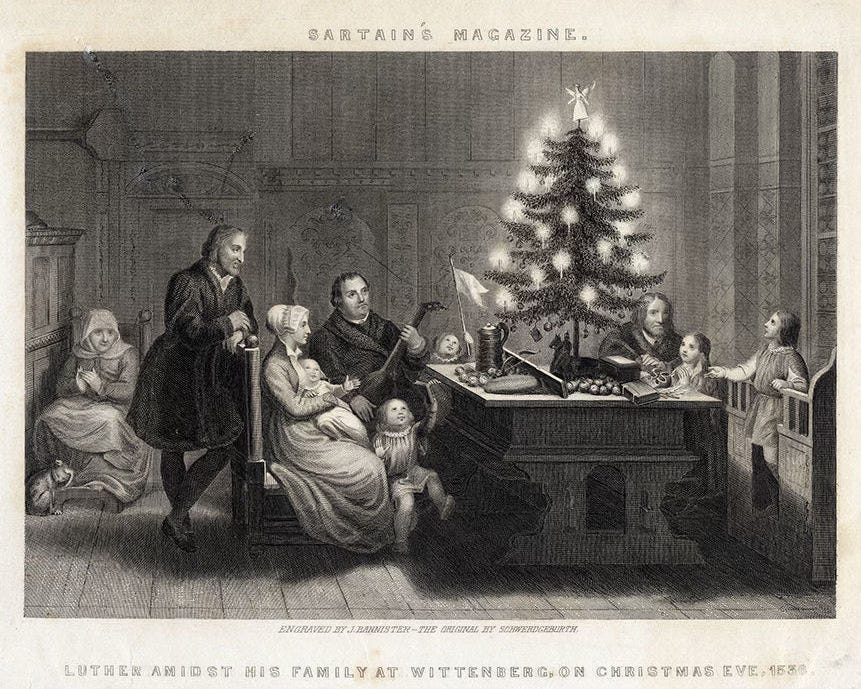

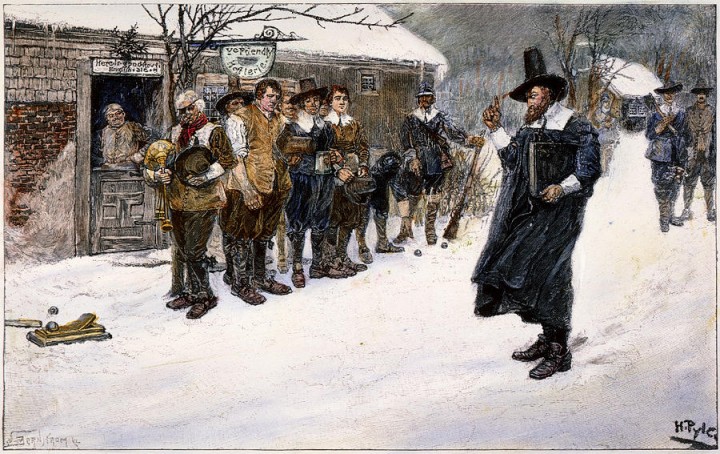

Puritan Governor interrupting the Christmas Sports,” by Howard Pyle c. 1883

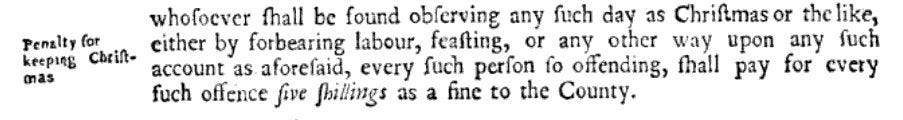

A short, easily-overlooked paragraph from an early law book of the Massachusetts Bay Colony reads as follows:

“For preventing disorders arising in several places within this jurisdiction, by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other countries, to the great dishonor of God and offence of others, it is therefore ordered by this Court and the authority thereof, that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon such accountants as aforesaid, every person so offending shall pay of every such offence five shillings, as a fine to the county.”

Yes, you read that right. In 1659 the Puritan government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony actually banned Christmas. So how did one of the largest Christian holidays come to be persecuted in the earliest days of New England?

Christmas in 17th century England actually wasn’t so different from the holiday we celebrate today. It was one of the largest religious observances, full of traditions, feast days, revelry and cultural significance. But the Puritans, a pious religious minority (who, after all, fled the persecution of the Anglican majority), felt that such celebrations were unnecessary and, more importantly, distracted from religious discipline. They also felt that due to the holiday’s loose pagan origins, celebrating it would constitute idolatry. A common sentiment among the leaders of the time was that such feast days detracted from their core beliefs: “They for whom all days are holy can have no holiday.”

This meant that Christmas wasn’t the only holiday on the chopping block. Easter and Whitsunday, other important historical celebrations, were also forbidden. Bans like these would continue through the 18th and 19th centuries (the US House of Representatives even convened on Christmas in 1802). As Puritanism started to fall out of favor, however, Christmas was almost universally accepted throughout the US by 1840, and was eventually declared a National Holiday in 1870.

This post was first published in 2015 and has been updated.

When Christmas Was Really Under Attack

The Puritans and the original “war on Christmas.”

Daniel N. Gullotta

Dec 19, 2021

Talk of the “war on Christmas” has become as much a part of the annual tradition in America as the tree, the tinsel, and the tracking of Santa on NORAD. The incidents that seem to rile people up, from workers saying “happy holidays” instead of “merry Christmas” to winter-but-not-quite-Christmas-themed Starbucks cups, while cringe-inducing, are largely harmless nontroversies. Thanks to SNL sketches and old monologues from The Colbert Report, it seems fair to say most people nowadays find talk of a war on Christmas to be less alarming than amusing. But earlier this month, the towering Fox New Christmas tree was set ablaze in New York City. Folks on Fox— a longtime purveyor of war-on-Christmas talk—understandably had a lot to say about the act of arboreal arson. Tucker Carlson called it “an attack of Christianity” and argued that the perpetrator should be convicted of a “hate crime.” An impassioned Ainsley Earhardt said that the Christmas tree “brings us together. It’s about the Christmas spirit. It is about the holiday season. It’s about Jesus. It’s about Hanukkah. It is about everything that we stand for as a country.”

But despite the image of Christmas as a quintessentially American holiday, the widespread celebration of Christmas across the United States is a surprisingly recent development. As historians Penne L. Restad and Stephen Nissenbaum have pointed out in their respective books on the American history of Christmas, it wasn’t until the middle of the nineteenth century that many Christmas traditions, such as gift-giving and sending seasonal cards, started to emerge in their recognizable forms. Only in the 1860s did Christmas start to gain recognition by various states as a legal holiday; not until June 26, 1870, did Congress declare December 25 a federal holiday.

What took so long? As strange as it might sound, the original “war on Christmas” was among Christians.

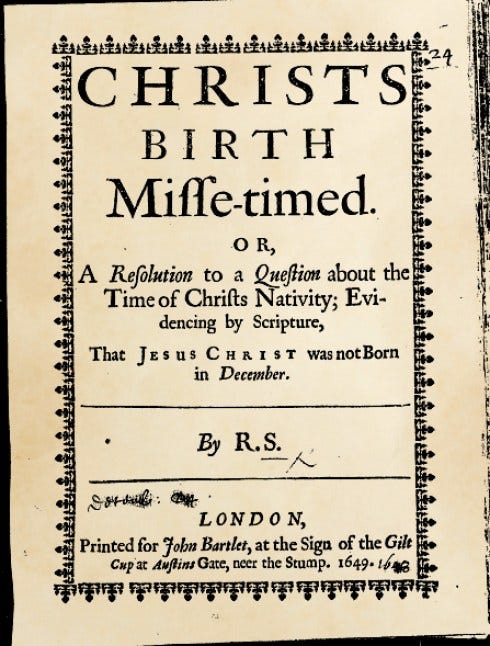

Because of Protestantism’s emphasis on biblical authority, some groups, like the Puritans, found the scriptural justification for Christmas lacking. While Jesus’ birth is referenced repeatedly and narrativized twice ( Matthew 1:18-25; Luke 2:1-7), December 25 is never referenced. The question of Christmas’s origins also became disputed, with Protestant theologians arguing that the celebratory date and many of its customs were pagan in origin, which seemed to lend credence to the Protestant belief that Catholic practices had corrupted Christianity. Through his own exegetical calculations, Robert Skinner’s Christs Birth Misse-timed (1649) argued that earlier Christians had miscalculated the date, further demonstrating that “all error cometh from Rome.”

The prolific Puritan pamphleteer William Prynne’s Histriomastix (1632) lambasted Christmas as nothing more than repacking of the Greco-Roman festival of Saturnalia by “paganizing Priests and Monks of popish (the same with the heathen Rome).” Likewise, Thomas Mockett, the Puritan rector of Gilston in Hertfordshire, argued that Christmas had been a Catholic plot to convert the unconverted masses using “riotous drinking, health drinking, gluttony, luxury, wantonness, dancing, dicing, stage-plays, interludes, masks, mummeries, with all other pagan sports.” The First Book of Discipline (1560), drafted in part by Scottish reformer John Knox, claimed Christmas among the things “that the Papists have invented.” Across the Atlantic world, Puritan clergymen and pamphleteers railed against Christmas as another “popish” and “pagan” error that true Christians need to do away with.

In addition to fierce anti-Catholic sentiment, the Puritan attacks on Christmas were also fueled by concerns over the indulgent conduct and frenzied atmosphere the holiday seemed to produce. It should be noted, despite their modern-day image as a grim lot who never knew how to have a good time and always wore black (when in fact, they wore all sorts of colorfully ‘sadd’ outfits), Puritans could be a merry bunch. They enjoyed drinking, singing, dancing, and sex as much as their less religiously extreme neighbors. But during these recreational activities, Puritan leaders always worried about the temptation of excess and were concerned that the festivities would become unchristian distractions. William Prynne complained of how Christians on “solemn feasts of Saints, especially of St. Nicholas,” would “honor Bacchus more than God” through “drunkenness and disorder.” Philip Stubbs, another provocative Puritan pamphleteer, described Christmas a time of “great wickedness,” bemoaning how such banqueting would devolve into scenes of mischief, with “dicing & carding” as well as “whordome.” Other Puritans also lamented how the true meaning of Christmas, namely the incarnation of Jesus, seemed lost on people who were instead more focused on partying. Given that the lead-up to Christmas often featured festivals and feasting, gateways to gluttony, drunkenness, mischief, and promiscuity, it is little wonder why the Puritans came to view the holiday with scorn.

Puritan efforts to quash the observance of Christmas did not manifest from pulpit preaching alone, but also through legal efforts and government action. With the Puritans in power in England following the execution of Charles I and the establishment of Cromwell’s Commonwealth, Parliament held regular sessions on December 25 to dispel any notion that there was something special about the day. In addition to fining those who desecrated their churches with seasonal decorations and threatening imprisonment to ministers who preached on the Nativity, Parliament outlawed Christmas plays in 1642. It upped the ante in 1647 by designating December 25 as day of repentance, signifying that it should be used for fasting, not feasting.

On this side of the Atlantic, the Mayflower Pilgrims likewise shunned the holiday, spending their first December 25 in the newly established Plymouth colony building houses. The Massachusetts Bay Colony also did not celebrate Christmas and passed a law in 1659 fining anyone “found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way” five shillings.

The Quakers of Pennsylvania also left Christmas unobserved for many of the same reasons. Unsurprisingly, New England almanacs dropped all references to December 25 as the date of Christ’s birth and references to Christmas celebrations are few and far between in colonial documentary records. In true Puritan style, Increase Mather wrote from New England in his pamphlet Against several Prophane and Superstitious Customs (1687), “The manner of Christ-mass-keeping, as generally observed, is highly dishonourable to the Name of Christ.”

But Christmas did not go down without a fight in England or the colonies. In the mother country, strict orders for markets and shops to remain open fell on deaf ears and for those who lived beyond the direct control of Puritan governance typically carried on with the festive merriment regardless. But Puritan mayors could also face protest through the holiday adornment of churches and businesses—as well as serious public backlash in the form of pro-Christmas rioting.

Meanwhile, the arrival of non-Puritans to the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies complicated the situation for those who had sought to escape England in order to form their own godly society. Only one year into his tenure as Plymouth’s governor, William Bradford encountered a group of newcomers to the colony who had excused themselves from work on December 25. Coastal towns like Marblehead in Massachusetts garnered a reputation for Christmas celebrations, much to the disapproval of their Puritan neighbors. One fisherman, William Hoar of Beverly (whose wife, Dorcas, was among the accused witches at Salem in 1692), hosted friends for Christmas drinking in 1662. Furthermore, as Stephen Nissenbaum has highlighted, the very existence and wording of the 1659 law “suggests that there were indeed people in Massachusetts who were observing Christmas in the late 1650s.” In fact, in 1659, the Massachusetts General Court remarked that there were “some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other countries,” like Christmas. Such details and data demonstrate the lingering Christmas spirit even in Puritan America.

With the restoration of the monarchy, many of the English laws decreed under Puritan rule were overturned, including the ones against Christmas. But the Puritans of New England resisted these changes. Puritan ministers continued to rage against holiday from the pulpit and in their personal writings long after the Massachusetts Bay Colony repealed the ban on Christmas. In a particularly dramatic display in 1686, the newly appointed governor, Sir Edmund Andros, surrounded himself with bodyguards at a Boston Christmas service for fear of protesters. Given this hostile environment and these anti-Christmas traditions, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Christmas remained a minor event for most American colonists. As Penne L. Restad observes, “It would take the project of nation-building in the wake of the Revolution to begin to define an American conception of Christmas.”

While today’s hand-wringing about the supposed war on Christmas centers on imagined attacks on American Christianity, there is a rich irony in the fact that the longest and most sustained critique of Christmas—including its banning—came from those who were claiming to be the truest and purest defenders of the reason for the season. |