Bloomberg news flow, about identity(ies) - anything to it?

bloomberg.com

The United States Is Southern Now

From booming metros to culture-defining exports, the South has quietly become a demographic powerhouse and a battleground for the country’s identity.

By Amanda Mull

August 15, 2025 at 5:00 PM GMT+8

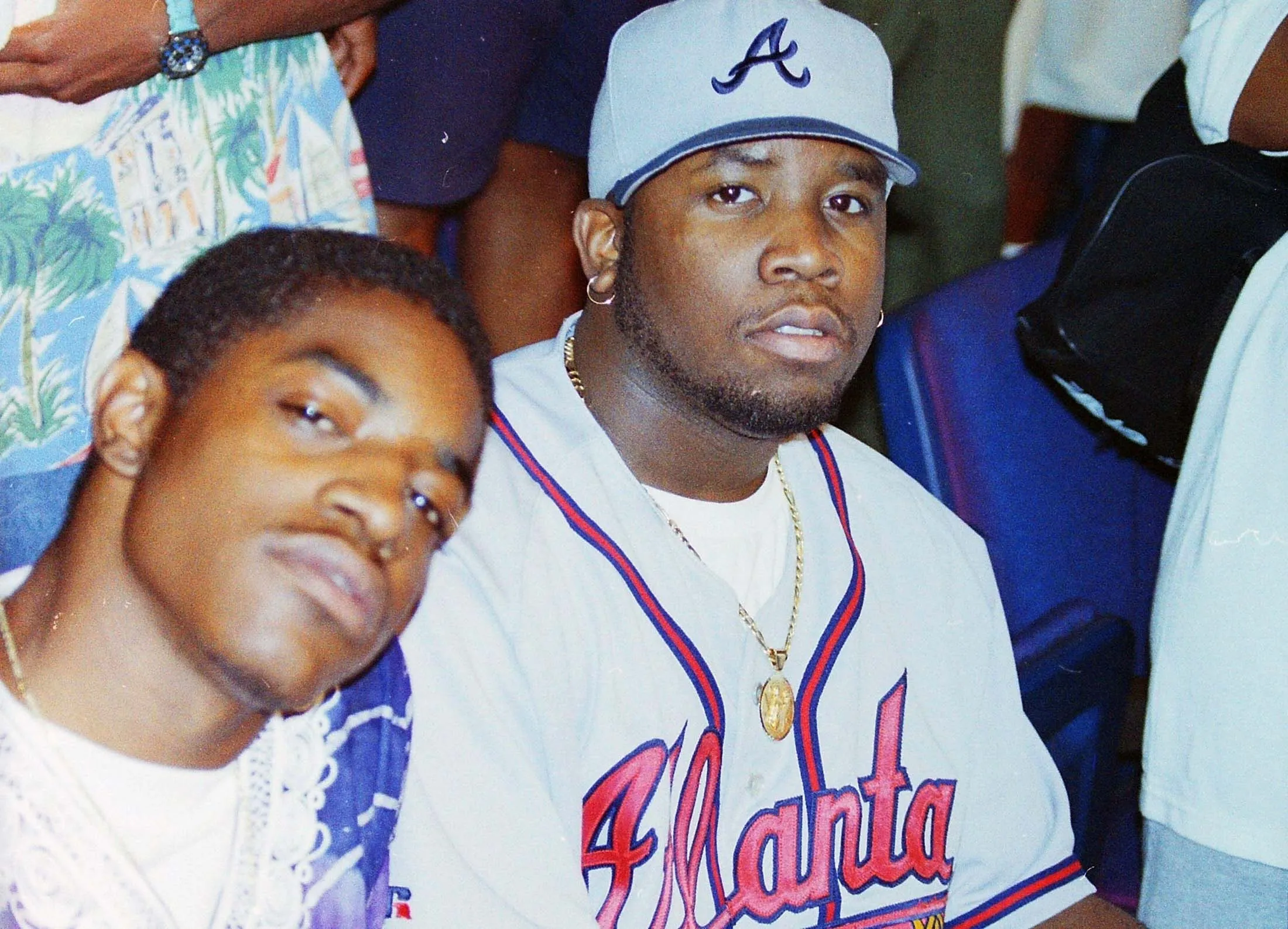

At the 1995 Source Awards, André Benjamin — you may know him as the rapper André 3000 — got up on a stage and spoke the future into existence. While accepting the award for best new rap group alongside Antwan “Big Boi” Patton, his collaborator in the Atlanta duo OutKast, André looked out at a crowd full of jeering East and West Coast hip-hop partisans, leaned over the mic and uttered a phrase that would go down as one of the greatest called shots since Babe Ruth: “The South got something to say.”

André, of course, was right about the future of hip-hop. Within a few years, the gravitational pull of the music industry would be yanked southward, producing an absurd list of stars that includes Beyoncé, Lil Wayne, Migos, Pharrell Williams and Travis Scott. But three decades later, it looks like he was also prescient about the trajectory of America as a whole. When OutKast accepted its award, the signs of a changing country were already there in the duo’s hometown: The metropolitan Atlanta area would see its population increase by 43% from 1990 to 2000, a growth rate that meant that an average of 360 new people put down roots in the Southeast’s most populous metro area every day for 10 years.

By 2020 the Atlanta metro area was home to more than 6 million people, a population swollen with transplants from the Northeast and the Rust Belt, in addition to a significant group of immigrants, largely from Asia and Latin America. Many of the region’s other metro areas — Nashville; Houston; Dallas; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Jacksonville, Florida, plus smaller cities like Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Durham, North Carolina — have followed similar trajectories over the past few decades. Combined, this growth has expanded the Southeast’s population at an annual compound rate of roughly 1% since 2010, easily the quickest growth of any region in the country.

As people go, so does culture. The recentering of the US population has brought with it a host of changes in the country’s economic, social and political life, from where cars are manufactured and movies are filmed to where the upwardly mobile send their kids to college and what they wear to signal status. And just as the South has changed the country, the country has changed the South too.

André 3000 and Big Boi, together known as Outkast, at the 1995 Source Awards.Photographer: Walik Goshorn/Alamy

There are a number of different moments where you could plausibly argue that America’s southbound future was guaranteed — the birth of the interstate highway system in 1956, the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, American Airlines’ and Delta’s respective choices of Dallas (1979) and Atlanta (1941) as their corporate hubs. As the historian Raymond Arsenault argued in a watershed 1984 paper, these events were crucial, but their impact on migration was maximized by another force. “Ask any southerner over thirty years of age to explain why the South has changed in recent decades, and he may begin with the civil rights movement or industrialization,” Arsenault wrote. “But sooner or later he will come around to the subject of air conditioning.”

In 1955 fewer than 2% of American homes had AC. In 1966, Texas became the first state to have it in more than half of its residences, and by the end of the decade, the entire South had hit that benchmark. Not coincidentally, in Arsenault’s view, the 1960s were the first decade since the Civil War that the South saw its population grow instead of decline, a reversal that was “startling” at the time. He attributes the shift both to the success of the Civil Rights Movement and to the multifaceted impacts of cooling in the region’s homes, workplaces, stores and medical facilities: Heat-related mortality plummeted, the region’s historically high levels of out-migration declined, and Northerners started moving south. In a 1970 editorial, the New York Times declared that year’s census “the air-conditioned census,” for the evident impact that the technology was already having on Americans’ migration between regions.

Up to that point, the South’s political and cultural isolation had left the region and its people at a bit of a remove from dominant American culture, and some of its leaders, still resentful at the forced end of Jim Crow, weren’t eager to invite outsiders in. But as time passed and AC became even more omnipresent, some state governments and prominent business figures saw an opportunity: They could market the region’s low taxes, cheap resources, permissive labor laws and poorly paid workers to attract employers and accelerate the South’s game of economic catch-up.

As the North began to deindustrialize and economic possibilities in many of its cities changed, state governments in the South set about building tax programs and incentive packages to lure manufacturing and warehouse jobs as well as corporate offices full of white-collar workers. One Georgia state program that ran from 1990 through 2012, for example, offered companies a per-employee bounty of $1,000 for jobs moved to the state’s less-developed counties — a program that over time became more permissive in which types of jobs qualified and where they could be located. Other states dangled similarly huge bundles of cash; in 2023, Volkswagen AG was awarded nearly $1.3 billion in subsidies from the state of South Carolina for a single auto plant.

The effort has largely worked as the region’s leaders had intended: Southern cities have become major hubs for millions of white-collar jobs in finance, law, consulting, energy, health care and the consumer sector, and those high-salary workers have bought up homes as fast as cities and suburbs are willing to build them, driving up property values. The South has also become a hub for manufacturing and for auto production in particular; it now produces twice as many of the country’s exports as the Midwest, including millions of luxury cars from the likes of BMW AG and Mercedes-Benz AG (which is currently in the process of moving its North American headquarters from New Jersey to Atlanta’s northern suburbs, joining Porsche).

For blue-collar workers on the region’s new assembly lines, the results have been more mixed: Their jobs tend to be lower-paying and more dangerous than the same work elsewhere in the country — a feature instead of a bug for their employers.

Just as the South has changed the country, the country has changed the South too.

As the population of the South changed, so did the policies implemented to shape its economic and cultural power. Attracting high-wage workers to the South wasn’t enough to guarantee that their kids — and those kids’ future earning potential — wouldn’t leave in search of the kind of prestigious college education that upwardly mobile American families have sought for generations. People tend to settle within the geographic footprint and alumni network of their university, so Southern leaders needed to convince Northern-born parents that the region’s flagship public universities — colleges that Southern elites have long used as finishing schools for their sons and daughters of privilege, but that were largely spurned by those outside the region — were a smart choice.

They did so with preferential admission and financial subsidies designed to stifle brain drain: Texas guaranteed admission to public universities for in-state kids who graduated in the top 10% of their high school class. Georgia implemented the HOPE Scholarship Program and Florida implemented the Bright Futures Scholarship Program, both of which use lottery revenue to pay in-state tuition for admitted students who meet certain academic benchmarks in high school, regardless of parental income. (In the interest of full disclosure: HOPE paid my tuition at the University of Georgia, as it did for virtually all of my friends in the mid-2000s.)

Hook 'Em the mascot celebrates with fans before a football game between the Texas Longhorns and the Oklahoma Sooners on Oct. 12, 2024 in Dallas.Photographer: David Buono/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

This suite of policies has been more successful than the people who implemented them decades ago probably could have imagined. Schools like the University of Texas at Austin, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Georgia and the University of Florida have all become far more selective over the past few decades, allowing them to grow in both size and prestige. UT, for example, has had to dial back automatic admissions for its flagship Austin campus to just the top 5% of the state’s high school graduating classes. When combined with the rising costs of private universities elsewhere, the programs have helped some Southern states reverse the brain drain problem entirely, attracting a growing number of out-of-state applicants who’ve never lived in the region.

That shift was exacerbated by the pandemic, at least in part because some parents were radicalized by their opposition to even modest public- health measures in states that kept kids home from school and restricted travel and leisure activities. Some of these parents chose to move their families to cheaper and more permissive (at least in some ways) Southern states, while others simply ended up more open to sending their kids there after high school. Many students, too, seemed to change their views of college during the same period, discovering a renewed interest in the experience itself. And, hey, warm weather and big-time college football seem fun, and paying full freight as an out-of-state student at UGA or UT is still cheaper in many cases than going somewhere smaller and snowier.

The South’s population has also changed in ways that don’t neatly fit assumptions about who exactly might want to live there. The region’s economy and culture have benefitted enormously from an influx of immigrants from around the world, largely to its major cities. In 2023 almost a quarter of Houston’s metro population were immigrants, including large communities of people from Mexico, Vietnam, Nigeria, India and China. From mid-2020 to mid-2024, two-thirds of the more than 200,000 people who moved to metro Atlanta were from another country.

The Great Migration, too, which saw millions of Black residents of the Jim Crow South flee north to escape slavery’s legacy of violence and repression, has begun to reverse. Black Americans have begun returning to the South in recent decades in search of job opportunities, a lower cost of living and the chance to be part of the region’s robust Black communities and culture. In 2021 the journalist and commentator Charles M. Blow published The Devil You Know, which called on Black Americans to move back to the South as he had, to retake the majoritarian political power in several states that they briefly held during Reconstruction.

That these changes have coincided with changes in how media is produced and distributed is no coincidence; air conditioning isn’t the only novel technology that has altered the trajectory of the South. For decades, the country’s art and entertainment worlds were highly concentrated in New York and Los Angeles, and mass media reflected its coastal origins, often proudly so. In July 1996, for example, the New Yorker mocked Atlanta’s role as host of the centennial Olympic Games with a cover illustration featuring a hayseed farmer in overalls, hoisting the Olympic torch in one hand and a piglet in the other.

Tourists visit the bars and country music venues in Nashville, which has become a hotspot for bachelorette parties.Photographer: Robert Alexander/Getty Images

More recently, changes in how American culture is produced have helped both to hasten the end of the region’s isolation and infuse more of its eccentricities into that culture at large. Some of these changes have been purposeful efforts to accrue cultural power in the region. The Atlanta Olympics; the courtship of expansion teams from professional football, basketball, baseball and soccer leagues; and Georgia’s and Louisiana’s huge tax break programs to attract major movie and television production facilities have all put the South and its inhabitants in front of more cameras and on more screens in recent decades.

When combined with the decentralizing influence of the internet, these efforts have fueled, among other things, the huge influence that Black Southerners now have on popular music. They’ve also changed how people get famous and who can accrue an audience. Bama Rushtok, a spontaneous, hugely popular TikTok event that chronicles the trials and tribulations (and outfits) of participants in sorority rush at the University of Alabama, has helped fuel interest in attending the region’s schools. MrBeast, aka Jimmy Donaldson, the most popular person on YouTube, sits atop a nascent empire with an estimated worth of as much as $1 billion from his home outside of Greenville, North Carolina, where he grew up.

You can see the further blending of Southern culture everywhere, if you look. Nashville, New Orleans and Charleston, South Carolina, have become popular destinations for bachelorette parties and girls trips from all over the country. Cowboy boots are trendy everywhere from Brooklyn, New York, to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The latest Wall Street status symbol is merch from the Masters golf tournament, held annually at Augusta National Golf Club in Georgia. Chick-fil-A Inc., a fast-food chain owned by a deeply religious family in Atlanta’s south suburbs, has successfully proliferated its franchises into virtually every corner of the country, even after years of localized opposition in more progressive states to its now-deceased patriarch’s support of anti-LGBTQ organizations. (The Louisiana-based chicken finger chain Raising Cane’s has become nationally ubiquitous with even more astonishing speed.)

America loves — and buys — pickup trucks more than it ever has before. Country stars like Morgan Wallen and Zach Bryan are some of the country’s most broadly popular musical acts, and artists like Texas natives Beyoncé and Post Malone have embraced the genre’s sounds and symbolism. “ A Bar Song (Tipsy),” one of 2024’s biggest hits, is a countryfied reimagining of a 2004 song by the St. Louis rapper J-Kwon. The new version is by Shaboozey, a Virginia-born Nigerian American whose music straddles both genres.

Post Malone (left) and Morgan Wallen perform onstage during the 57th Annual CMA Awards on Nov. 8, 2023 in Nashville.Photographer: Astrida Valigorsky/Getty Images

Of course, it’s impossible to miss that national interest in Southern culture — or, at least, in its aesthetic signifiers — has spiked when a wide swath of the country itself seems to be in a revanchist mood. The South’s reputation as a place of racial domination makes it a powerful symbol for the White Americans who feel like their status atop the country’s racial hierarchy has been unduly challenged.

The Lost Cause vision of the Confederacy has begun to gain ground again, as part of the backlash to 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests; the Trump administration recently announced that a Washington, DC, statue of a Confederate general that had been felled during those protests would soon rise again. And much of the South’s current leadership appears happy to cling to parts of that past with both hands, whether that means gerrymandering their states to stifle the power of Black voters or marketing their disproportionately Black blue-collar workforces to national and international corporations as easier to underpay and exploit.

This fight for the soul of the South is nothing less than a fight over the future of America itself. The region’s recent trajectory of expansion, diversification and political moderation would not have been possible without ending Jim Crow and prying the bluntest instruments of racial domination from the hands of Southern elites. Now there is a real push to give those tools back — not just to Southerners but to wannabe Confederates across the country. But revanchists looking to today’s South as an answer to their prayers might be disappointed in what they find: a region that has become more like the rest of the US, which has in turn become more like it.

That, and a lot of central air conditioning. But as the South’s heat and humidity has spread north over time — enabling magnolias, dogwoods and camellias to thrive as far afield as New York City — that, too, is pretty much everywhere now. |