The Weather Underground

A Window into Left Wing Terror

Memetic Sisyphus

Sep 18, 2025

The Weather Underground began as a college-based movement, emerging from the activist culture of the late 1960s. Initially operating in the open, it organized public demonstrations against what it saw as the “imperialist” policies of the United States. Its roots can be traced to 1969, when the group first convened under the banner of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

In the late 1960s, the future founders of the Weather Underground participated in the Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP), an initiative launched by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) between 1963 and 1968. The program sought to organize an interracial movement of the poor in Northern urban neighborhoods, with the aim of securing full and fair employment, guaranteed annual income, and expanded political rights for working-class and impoverished Americans. The vision was ambitious: a more democratic society that would ensure political freedom, economic and physical security, abundant education, and opportunities for cultural diversity.

The project was rooted in a Marxist interpretation of poverty; that capitalism itself produced inequality and social ills. These interpretations are wrong, and in practice the ERAP failed to achieve its goals. Economic opportunities never materialized, and the effort to mobilize impoverished neighborhoods often fueled more instability rather than progress. Instead of fostering empowerment, it deepened cycles of poverty and crime. Disillusioned, many activists concluded that incremental reform was impossible; only a full-scale violent revolution, could bring about real change.

They soon rallied behind the anti-war movement of the 1970s. Their supposed opposition to violence was a cover for their true agenda: a violent domestic revolution. Building networks across the country, especially within universities, they forged alliances with left-wing social groups such as the Progressive Labor Party, the Revolutionary Youth Movement, the Black Panthers, and a range of communist agitators.

At a communist convention held in 1969 the members of the SDS wrote a manifesto laying out the weatherman’s political ideals:

“The most important task for us toward making the revolution, and the work our collectives should engage in, is the creation of a mass revolutionary movement, without which a clandestine revolutionary party will be impossible. A revolutionary mass movement is different from the traditional revisionist mass base of "sympathizers". Rather it is akin to the Red Guard in China, based on the full participation and involvement of masses of people in the practice of making revolution; a movement with a full willingness to participate in the violent and illegal struggle.”

It was signed by Karen Ashley, Bill Ayers, Bernardine Dohrn, John Jacobs, Jeff Jones, Gerry Long, Howie Machtinger, Jim Mellen, Terry Robbins, Mark Rudd, and Steve Tappis.

The newly named weatherman’s first action was “to bring the war home” a two-pronged agenda of ending the war in Vietnam and starting a violent communist revolution in the United States.

“Weatherman would shove the war down their dumb, fascist throats and show them, while we were at it, how much better we were than them, both tactically and strategically, as a people. In an all-out civil war over Vietnam and other fascist U.S. imperialism”

It is easy to see modern left-wing sentiments reflected in these early writings. The Weather Underground cast themselves as an American counterpart to Mao’s Red Guards, envisioning a cultural revolution that would sweep the nation and, ultimately, the world into global communism. They helped popularize ideas such as “white privilege” and narratives of systemic white oppression. To them, Black revolutionary struggle was not only a moral cause but also a potential spark for a broader conflict. In pursuit of this, they lent their support to nearly every radical Black movement they could find.

Bernardine Dohrn said in 1970, "White youth must choose sides now. They must either fight on the side of the oppressed or be on the side of the oppressor." She would later go on to become a professor at the university of Illinois.

Another quote from an unnamed member during this time: “White and male supremacy are built into every social structure and institution: churches, schools, the press, literature and art. All social concepts and behavior are developed in the adequate fashion to insure imperialist rule … White and male supremacy are rooted in the material base of imperialism … the ideology of the oppressor nation.”

Some of the Weather Underground’s first actions were the “Days of Rage,” a series of demonstrations held in Chicago in October 1969. These were not carefully planned political actions but chaotic outbursts meant to “bring the war home” by breaking social order and attacking symbols of authority. Hundreds of young radicals flooded the streets, smashing windows, setting fires, and clashing with police. Participants boasted of rejecting restraint, engaging in vandalism, violence, and public displays of sexuality. Police responded with force, beating and arresting scores of protesters. Though widely promoted as the spark of revolution, the event ended in failure, leaving behind destruction, dozens of injuries, and more than 280 arrests.

After the failure of the Days of Rage, Weather Underground leaders shifted strategy. Large, public demonstrations were abandoned in favor of clandestine guerrilla tactics of sabotage and violence. The organization restructured into small “collectives” or terror cells spread across the country, each encouraged to carry out acts of sabotage against police, government institutions, and symbols of American power.

Life inside these cells demanded strict ideological conformity. Members were subjected to what they called criticism–self-criticism (CSC) sessions, also referred to as “Weatherfries.” In these struggle-style meetings, anyone who questioned the collective’s methods or beliefs was pressured to confess their “errors,” reaffirm loyalty to the revolutionary line, and accept public shaming from their comrades. One former member later described the atmosphere of these gatherings as equal parts indoctrination and coercion, designed to break down individuality and enforce ideological purity.

Doug McAdam describes the topic of conversation in one such session: “The question that was debated was it or was it not the duty of every good revolutionary to kill all newborn white babies… for no fault of their own these kids will grow up to be part of an oppressive racial establishment internationally, so your duty is to kill them.” Doug goes on to explain how one objection was quickly shouted down.

In New York, members of the Weather Underground firebombed the home of Judge John M. Murtagh, who was presiding over the trial of the “Panther 21” Black Panther Party members accused of plotting to bomb New York landmarks. On February 21, 1970, around 4:30 a.m., three Molotov cocktails exploded at his residence at 529 W. 217th Street in the Inwood neighborhood. Although the judge and his family were unharmed, the attack caused significant property damage, including shattered windows, scorched eaves, and a charred car. The perpetrators left graffiti reading “Free the Panther 21” and “Viet Cong have won” on the sidewalk. The Weather Underground claimed responsibility for the bombing, viewing it as an act of solidarity with the Black Panther Party.

Later in the same year, they planned to bomb a dance for military personnel returning home from Vietnam. However, their plot never came to fruition: the members’ own bomb-making operation in Greenwich Village accidentally detonated, destroying their townhouse and injuring several of the group. The nation was spared greater tragedy due the incompetence of communist terrorists.

By this point, the Weather Underground had gone fully “underground,” restricting membership to small, tightly controlled cells. In 1970, the group issued a Declaration of War against the United States, formalizing its commitment to revolutionary violence. Over the next several years, they carried out a nationwide bombing campaign, targeting government and military sites as well as symbols of American power. Their attacks included office buildings, military recruitment centers, the Pentagon, the State Department, and even the U.S. Capitol building.

The Weather Underground’s high-profile attacks drew significant law enforcement attention. Many members were arrested in connection with these bombings, but most cases were ultimately dismissed. A key factor was a new law requiring court authorization for electronic surveillance; evidence obtained without a warrant was inadmissible in court. As a result, several founding members effectively avoided prosecution for even their most audacious plots, including planned attacks on the U.S. Capitol, escaping legal consequences despite the severity of their actions.

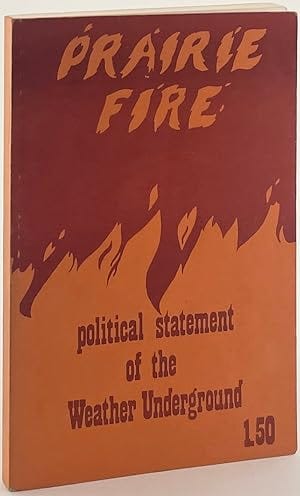

In the mid-1970s, the Weather Underground, led by Bill Ayers, published Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism, a manifesto inspired by Mao Zedong's assertion that "a single spark can set a prairie fire." This document marked a significant shift in their strategy, explicitly endorsing violent revolution against the United States. The manifesto declared, "Active combat against empire is the only foundation for socialist revolution in the oppressor nation," emphasizing their commitment to armed struggle as the primary means of achieving their goals. It further stated, "We are a guerrilla organization. We are communist women and men, underground in the United States for more than four years," highlighting their clandestine operations and ideological stance. Prairie Fire resonated within radical circles, spreading across left-wing organizations nationwide and solidifying the Weather Underground's influence in the radical movement of the era.

By the mid-1970s, the Weather Underground had split into two distinct factions. The “Prairie Collective” remained relatively open and less violent, focusing on organizing and propaganda, while the May 19th Communist Organization (M19CO) embraced a more militant and clandestine approach. The May 19th cell collaborated with Black communist groups on a series of jailbreaks and carried out escalating armed robberies, culminating in the notorious 1981 Brinks armored truck heist, during which three people were killed. By 1986, law enforcement had dismantled both factions, with members either captured, imprisoned, or, in some cases, killed.

What distinguishes the Weather Underground is not merely their violent tactics, but the trajectories of their members post-activism. Bill Ayers, a co-founder of the group, became a professor of education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. In the 1990s, he collaborated with Barack Obama on the board of the Woods Fund of Chicago, a philanthropic organization. He later ghost wrote Obama’s memoirs.

The broader Weather Underground network also saw its members transition into academia and policy making. Bernardine Dohrn, another key figure, became a tenured professor at Northwestern University School of Law. These individuals have influenced educational and political landscapes, shaping policies and ideologies that persist today.

In future posts, I will delve deeper into these connections, examining how former Weather Underground members have integrated into mainstream left-wing institutions and their impact on contemporary political thought.

memeticsisyphus.substack.com |