I’m the Canadian who was detained by Ice for two weeks. It felt like I had been kidnapped

I was stuck in a freezing cell without explanation despite eventually having lawyers and media attention. Yet, compared with others, I was lucky

Jasmine Mooney

Wed 19 Mar 2025 09.00 GMT

There was no explanation, no warning. One minute, I was in an immigration office talking to an officer about my work visa, which had been approved months before and allowed me, a Canadian, to work in the US. The next, I was told to put my hands against the wall, and patted down like a criminal before being sent to an Ice detention center without the chance to talk to a lawyer.

I grew up in Whitehorse, Yukon, a small town in the northernmost part of Canada. I always knew I wanted to do something bigger with my life. I left home early and moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, where I built a career spanning multiple industries – acting in film and television, owning bars and restaurants, flipping condos and managing Airbnbs.

In my 30s, I found my true passion working in the health and wellness industry. I was given the opportunity to help launch an American brand of health tonics called Holy! Water – a job that would involve moving to the US.

I was granted my trade Nafta work visa, which allows Canadian and Mexican citizens to work in the US in specific professional occupations, on my second attempt. It goes without saying, then, that I have no criminal record. I also love the US and consider myself to be a kind, hard-working person.

I started working in California and travelled back and forth between Canada and the US multiple times without any complications – until one day, upon returning to the US, a border officer questioned me about my initial visa denial and subsequent visa approval. He asked why I had gone to the San Diego border the second time to apply. I explained that that was where my lawyer’s offices were, and that he had wanted to accompany me to ensure there were no issues.

After a long interrogation, the officer told me it seemed “shady” and that my visa hadn’t been properly processed. He claimed I also couldn’t work for a company in the US that made use of hemp – one of the beverage ingredients. He revoked my visa, and told me I could still work for the company from Canada, but if I wanted to return to the US, I would need to reapply.

I was devastated; I had just started building a life in California. I stayed in Canada for the next few months, and was eventually offered a similar position with a different health and wellness brand.

I restarted the visa process and returned to the same immigration office at the San Diego border, since they had processed my visa before and I was familiar with it. Hours passed, with many confused opinions about my case. The officer I spoke to was kind but told me that, due to my previous issues, I needed to apply for my visa through the consulate. I told her I hadn’t been aware I needed to apply that way, but had no problem doing it.

Then she said something strange: “You didn’t do anything wrong. You are not in trouble, you are not a criminal.”

I remember thinking: Why would she say that? Of course I’m not a criminal!

She then told me they had to send me back to Canada. That didn’t concern me; I assumed I would simply book a flight home. But as I sat searching for flights, a man approached me.

“Come with me,” he said.

There was no explanation, no warning. He led me to a room, took my belongings from my hands and ordered me to put my hands against the wall. A woman immediately began patting me down. The commands came rapid-fire, one after another, too fast to process.

They took my shoes and pulled out my shoelaces.

“What are you doing? What is happening?” I asked.

“You are being detained.”

“I don’t understand. What does that mean? For how long?”

“I don’t know.”

That would be the response to nearly every question I would ask over the next two weeks: “I don’t know.”

They brought me downstairs for a series of interviews and medical questions, searched my bags and told me I had to get rid of half my belongings because I couldn’t take everything with me.

“Take everything with me where?” I asked.

A woman asked me for the name of someone they could contact on my behalf. In moments like this, you realize you don’t actually know anyone’s phone number anymore. By some miracle, I had recently memorized my best friend Britt’s number because I had been putting my grocery points on her account.

I gave them her phone number.

They handed me a mat and a folded-up sheet of aluminum foil.

“What is this?”

“Your blanket.”

“I don’t understand.”

I was taken to a tiny, freezing cement cell with bright fluorescent lights and a toilet. There were five other women lying on their mats with the aluminum sheets wrapped over them, looking like dead bodies. The guard locked the door behind me.

A border patrol agent watches as girls from Central America sleep under thermal blankets at a detention facility in McAllen, Texas, on 8 September 2014. Photograph: John Moore/Getty ImagesFor two days, we remained in that cell, only leaving briefly for food. The lights never turned off, we never knew what time it was and no one answered our questions. No one in the cell spoke English, so I either tried to sleep or meditate to keep from having a breakdown. I didn’t trust the food, so I fasted, assuming I wouldn’t be there long.

On the third day, I was finally allowed to make a phone call. I called Britt and told her that I didn’t understand what was happening, that no one would tell me when I was going home, and that she was my only contact.

They gave me a stack of paperwork to sign and told me I was being given a five-year ban unless I applied for re-entry through the consulate. The officer also said it didn’t matter whether I signed the papers or not; it was happening regardless.

I was so delirious that I just signed. I told them I would pay for my flight home and asked when I could leave.

No answer.

Then they moved me to another cell – this time with no mat or blanket. I sat on the freezing cement floor for hours. That’s when I realized they were processing me into real jail: the Otay Mesa Detention Center.

The Otay Mesa Detention Center in Otay Mesa, California, on 9 May 2020. Photograph: Sandy Huffaker/AFP/Getty ImagesI was told to shower, given a jail uniform, fingerprinted and interviewed. I begged for information.

“How long will I be here?”

“I don’t know your case,” the man said. “Could be days. Could be weeks. But I’m telling you right now – you need to mentally prepare yourself for months.”

Months.

I felt like I was going to throw up.

I was taken to the nurse’s office for a medical check. She asked what had happened to me. She had never seen a Canadian there before. When I told her my story, she grabbed my hand and said: “Do you believe in God?”

I told her I had only recently found God, but that I now believed in God more than anything.

“I believe God brought you here for a reason,” she said. “I know it feels like your life is in a million pieces, but you will be OK. Through this, I think you are going to find a way to help others.”

At the time, I didn’t know what that meant. She asked if she could pray for me. I held her hands and wept.

I felt like I had been sent an angel.

I was then placed in a real jail unit: two levels of cells surrounding a common area, just like in the movies. I was put in a tiny cell alone with a bunk bed and a toilet.

The best part: there were blankets. After three days without one, I wrapped myself in mine and finally felt some comfort.

For the first day, I didn’t leave my cell. I continued fasting, terrified that the food might make me sick. The only available water came from the tap attached to the toilet in our cells or a sink in the common area, neither of which felt safe to drink.

Eventually, I forced myself to step out, meet the guards and learn the rules. One of them told me: “No fighting.”

“I’m a lover, not a fighter,” I joked. He laughed.

I asked if there had ever been a fight here.

“In this unit? No,” he said. “No one in this unit has a criminal record.”

That’s when I started meeting the other women.

That’s when I started hearing their stories.

Women sit on their beds in a privately run 1,000-bed detention center on 28 February 2006 in Otay Mesa, California. Photograph: Robert Nickelsberg/Getty ImagesAnd that’s when I made a decision: I would never allow myself to feel sorry for my situation again. No matter how hard this was, I had to be grateful. Because every woman I met was in an even more difficult position than mine.

There were around 140 of us in our unit. Many women had lived and worked in the US legally for years but had overstayed their visas – often after reapplying and being denied. They had all been detained without warning.

If someone is a criminal, I agree they should be taken off the streets. But not one of these women had a criminal record. These women acknowledged that they shouldn’t have overstayed and took responsibility for their actions. But their frustration wasn’t about being held accountable; it was about the endless, bureaucratic limbo they had been trapped in.

The real issue was how long it took to get out of the system, with no clear answers, no timeline and no way to move forward. Once deported, many have no choice but to abandon everything they own because the cost of shipping their belongings back is too high.

I met a woman who had been on a road trip with her husband. She said they had 10-year work visas. While driving near the San Diego border, they mistakenly got into a lane leading to Mexico. They stopped and told the agent they didn’t have their passports on them, expecting to be redirected. Instead, they were detained. They are both pastors.

I met a family of three who had been living in the US for 11 years with work authorizations. They paid taxes and were waiting for their green cards. Every year, the mother had to undergo a background check, but this time, she was told to bring her whole family. When they arrived, they were taken into custody and told their status would now be processed from within the detention center.

Another woman from Canada had been living in the US with her husband who was detained after a traffic stop. She admitted she had overstayed her visa and accepted that she would be deported. But she had been stuck in the system for almost six weeks because she hadn’t had her passport. Who runs casual errands with their passport?

One woman had a 10-year visa. When it expired, she moved back to her home country, Venezuela. She admitted she had overstayed by one month before leaving. Later, she returned for a vacation and entered the US without issue. But when she took a domestic flight from Miami to Los Angeles, she was picked up by Ice and detained. She couldn’t be deported because Venezuela wasn’t accepting deportees. She didn’t know when she was getting out.

There was a girl from India who had overstayed her student visa for three days before heading back home. She then came back to the US on a new, valid visa to finish her master’s degree and was handed over to Ice due to the three days she had overstayed on her previous visa.

There were women who had been picked up off the street, from outside their workplaces, from their homes. All of these women told me that they had been detained for time spans ranging from a few weeks to 10 months. One woman’s daughter was outside the detention center protesting for her release.

That night, the pastor invited me to a service she was holding. A girl who spoke English translated for me as the women took turns sharing their prayers – prayers for their sick parents, for the children they hadn’t seen in weeks, for the loved ones they had been torn away from.

Then, unexpectedly, they asked if they could pray for me. I was new here, and they wanted to welcome me. They formed a circle around me, took my hands and prayed. I had never felt so much love, energy and compassion from a group of strangers in my life. Everyone was crying.

At 3am the next day, I was woken up in my cell.

“Pack your bag. You’re leaving.”

I jolted upright. “I get to go home?”

The officer shrugged. “I don’t know where you’re going.”

Of course. No one ever knew anything.

I grabbed my things and went downstairs, where 10 other women stood in silence, tears streaming down their faces. But these weren’t happy tears. That was the moment I learned the term “transferred”.

For many of these women, detention centers had become a twisted version of home. They had formed bonds, established routines and found slivers of comfort in the friendships they had built. Now, without warning, they were being torn apart and sent somewhere new. Watching them say goodbye, clinging to each other, was gut-wrenching.

I had no idea what was waiting for me next. In hindsight, that was probably for the best.

Our next stop was Arizona, the San Luis Regional Detention Center. The transfer process lasted 24 hours, a sleepless, grueling ordeal. This time, men were transported with us. Roughly 50 of us were crammed into a prison bus for the next five hours, packed together – women in the front, men in the back. We were bound in chains that wrapped tightly around our waists, with our cuffed hands secured to our bodies and shackles restraining our feet, forcing every movement into a slow, clinking struggle.

When we arrived at our next destination, we were forced to go through the entire intake process all over again, with medical exams, fingerprinting – and pregnancy tests; they lined us up in a filthy cell, squatting over a communal toilet, holding Dixie cups of urine while the nurse dropped pregnancy tests in each of our cups. It was disgusting.

We sat in freezing-cold jail cells for hours, waiting for everyone to be processed. Across the room, one of the women suddenly spotted her husband. They had both been detained and were now seeing each other for the first time in weeks.

The look on her face – pure love, relief and longing – was something I’ll never forget.

We were beyond exhausted. I felt like I was hallucinating.

The guard tossed us each a blanket: “Find a bed.”

There were no pillows. The room was ice cold, and one blanket wasn’t enough. Around me, women lay curled into themselves, heads covered, looking like a room full of corpses. This place made the last jail feel like the Four Seasons.

I kept telling myself: Do not let this break you.

Thirty of us shared one room. We were given one Styrofoam cup for water and one plastic spoon that we had to reuse for every meal. I eventually had to start trying to eat and, sure enough, I got sick. None of the uniforms fit, and everyone had men’s shoes on. The towels they gave us to shower were hand towels. They wouldn’t give us more blankets. The fluorescent lights shined on us 24/7.

Everything felt like it was meant to break you. Nothing was explained to us. I wasn’t given a phone call. We were locked in a room, no daylight, with no idea when we would get out.

I tried to stay calm as every fiber of my being raged towards panic mode. I didn’t know how I would tell Britt where I was. Then, as if sent from God, one of the women showed me a tablet attached to the wall where I could send emails. I only remembered my CEO’s email from memory. I typed out a message, praying he would see it.

He responded.

Through him, I was able to connect with Britt. She told me that they were working around the clock trying to get me out. But no one had any answers; the system made it next to impossible. I told her about the conditions in this new place, and that was when we decided to go to the media.

She started working with a reporter and asked whether I would be able to call her so she could loop him in. The international phone account that Britt had previously tried to set up for me wasn’t working, so one of the other women offered to let me use her phone account to make the call.

We were all in this together.

With nothing to do in my cell but talk, I made new friends – women who had risked everything for the chance at a better life for themselves and their families.

Through them, I learned the harsh reality of seeking asylum. Showing me their physical scars, they explained how they had paid smugglers anywhere from $20,000 to $60,000 to reach the US border, enduring brutal jungles and horrendous conditions.

One woman had been offered asylum in Mexico within two weeks but had been encouraged to keep going to the US. Now, she was stuck, living in a nightmare, separated from her young children for months. She sobbed, telling me how she felt like the worst mother in the world.

Many of these women were highly educated and spoke multiple languages. Yet, they had been advised to pretend they didn’t speak English because it would supposedly increase their chances of asylum.

Some believed they were being used as examples, as warnings to others not to try to come.

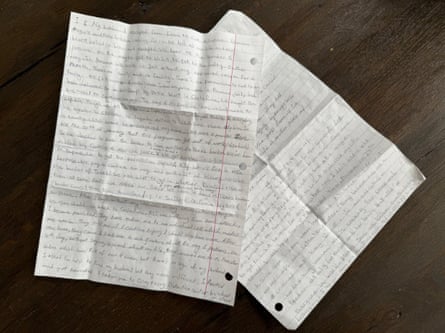

Women were starting to panic in this new facility, and knowing I was most likely the first person to get out, they wrote letters and messages for me to send to their families.

Some of the letters given to Jasmine Mooney from the women she met during her time in Ice detention facilities. Photograph: Jasmine MooneyIt felt like we had all been kidnapped, thrown into some sort of sick psychological experiment meant to strip us of every ounce of strength and dignity.

We were from different countries, spoke different languages and practiced different religions. Yet, in this place, none of that mattered. Everyone took care of each other. Everyone shared food. Everyone held each other when someone broke down. Everyone fought to keep each other’s hope alive.

I got a message from Britt. My story had started to blow up in the media.

Almost immediately after, I was told I was being released.

My Ice agent, who had never spoken to me, told my lawyer I could have left sooner if I had signed a withdrawal form, and that they hadn’t known I would pay for my own flight home.

From the moment I arrived, I begged every officer I saw to let me pay for my own ticket home. Not a single one of them ever spoke to me about my case.

To put things into perspective: I had a Canadian passport, lawyers, resources, media attention, friends, family and even politicians advocating for me. Yet, I was still detained for nearly two weeks.

Imagine what this system is like for every other person in there.

A small group of us were transferred back to San Diego at 2am – one last road trip, once again shackled in chains. I was then taken to the airport, where two officers were waiting for me. The media was there, so the officers snuck me in through a side door, trying to avoid anyone seeing me in restraints. I was beyond grateful that, at the very least, I didn’t have to walk through the airport in chains.

To my surprise, the officers escorting me were incredibly kind, and even funny. It was the first time I had laughed in weeks.

I asked if I could put my shoelaces back on.

“Yes,” one of them said with a grin. “But you better not run.”

“Yeah,” the other added. “Or we’ll have to tackle you in the airport. That’ll really make the headlines.”

I laughed, then told them I had spent a lot of time observing the guards during my detention and I couldn’t believe how often I saw humans treating other humans with such disregard. “But don’t worry,” I joked. “You two get five stars.”

When I finally landed in Canada, my mom and two best friends were waiting for me. So was the media. I spoke to them briefly, numb and delusional from exhaustion.

It was surreal listening to my friends recount everything they had done to get me out: working with lawyers, reaching out to the media, making endless calls to detention centers, desperately trying to get through to Ice or anyone who could help. They said the entire system felt rigged, designed to make it nearly impossible for anyone to get out.

The reality became clear: Ice detention isn’t just a bureaucratic nightmare. It’s a business. These facilities are privately owned and run for profit.

Companies like CoreCivic and GEO Group receive government funding based on the number of people they detain, which is why they lobby for stricter immigration policies. It’s a lucrative business: CoreCivic made over $560m from Ice contracts in a single year. In 2024, GEO Group made more than $763m from Ice contracts.

The more detainees, the more money they make. It stands to reason that these companies have no incentive to release people quickly. What I had experienced was finally starting to make sense.

‘I escaped one gulag only to end up in another’: Russian asylum seekers face Ice detention in the US

Read more

This is not just my story. It is the story of thousands and thousands of people still trapped in a system that profits from their suffering. I am writing in the hope that someone out there – someone with the power to change any of this – can help do something.

The strength I witnessed in those women, the love they gave despite their suffering, is what gives me faith. Faith that no matter how flawed the system, how cruel the circumstances, humanity will always shine through.

Even in the darkest places, within the most broken systems, humanity persists. Sometimes, it reveals itself in the smallest, most unexpected acts of kindness: a shared meal, a whispered prayer, a hand reaching out in the dark. We are defined by the love we extend, the courage we summon and the truths we are willing to tell.

This article was amended on 18 April 2025 to remove an image which had been manipulated in breach of editorial standards. |