something, from the time of get-go

scmp.com

2,000-year-old machine found in western China tomb could be a binary computer: authorities

Sophisticated silk-weaving loom dating back to the Western Han dynasty used physical pattern cards which acted like ancient software

Shi Huang

Published: 2:00pm, 2 Jan 2026

The computer, at its core, is an input-output device: it receives instructions, executes programmes, performs calculations automatically and produces results.

By this fundamental definition, China’s ancient ti hua ji, or figured loom – dating back more than two millennia to the Western Han dynasty – may well be recognised as the world’s earliest computer, according to the China Association for Science and Technology (CAST).

Unearthed in 2012 from a tomb dated around 150BC in Chengdu, this sophisticated silk-weaving machine made use of programmable computation. Its “programme” came in the form of physical pattern cards – the ancient equivalent of software – which directed the lifting of individual warp threads according to a preset design.

A raised warp thread represents 1, while a lowered one represents 0.

It is the world’s oldest known “computer hardware”, with corresponding “software” – the figure loom programme, CAST said in a video posted on its social media account on December 27.

CAST is China’s largest official scientific body. Its entry into the global debate over who invented the first computer, and the public endorsement of the Chengdu loom as proto-computing hardware, signals a growing momentum to rewrite technological history from a non-Western perspective.

For generations, the narrative has held that science and computing originated in Europe. But as China comes back to the forefront of global technological leadership – from 5G, AI to robotics – its people are reclaiming a forgotten legacy that Chinese artisans had already mastered the principles of programmability, automation and information encoding more than 2,000 years ago.

The Chengdu machine used 10,470 longitudinal warp threads controlled by 86 brown “programming” patches, governing more than 9.6 million intersections with the latitudinal weft threads. Once programmed, it could operate simultaneously on 100 devices, producing results – specifically, intricately woven silk patterns – with perfect precision.

All silk fabrics are woven from warp (longitudinal) and weft (latitudinal) threads. Following a pre-designed pattern, weavers had to carefully lift specific warp threads at precise positions, allowing the shuttle to pass through with different coloured weft threads.

This process significantly increased the workload. China addressed this challenge early on through mechanisation, which established it as the world’s silk production centre. However, the precise timeline of this development remained unclear for centuries.

In December 2012, during the construction of Chengdu Metro Line 3, a Western Han dynasty tomb was discovered at the Laoguan Mountain site.

Chengdu’s archaeological team promptly conducted a salvage excavation, which unexpectedly resolved this historical mystery. During the excavation of Tomb No 2, archaeologists discovered four loom models in the sediment at the base of the northern chamber.

Well preserved and structurally complex, with remnants of silk threads and dyes on their components, these models were identified by textile experts as the earliest known complete figure looms, not only in China but worldwide.

This discovery was selected as one of China’s Top 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2013. Through archaeological research, China has since reconstructed this automatic loom and clarified its working principles.

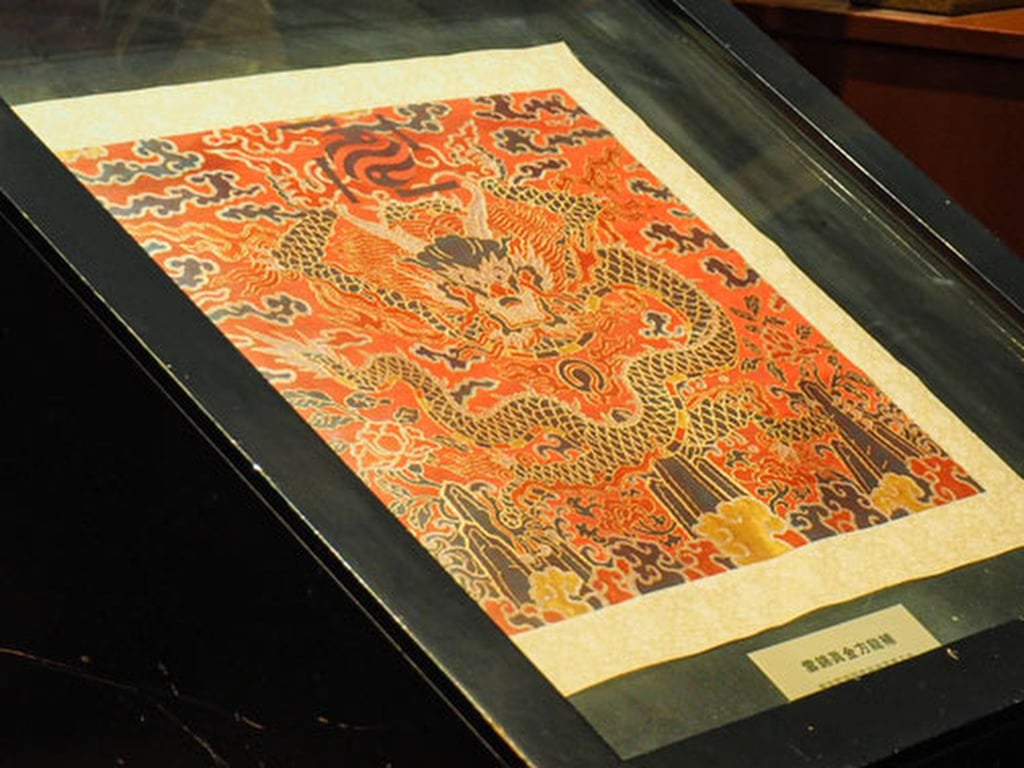

An artwork created using the ancient Chinese loom machine, which dates back over two millennia to the Western Han dynasty. Photo: China Silk Museum

This automatic figure loom operated via a “pattern book” – a programmed design template analogous to modern punch cards.

The craftsman would first translate a designed pattern into a physical sequence using threads or bamboo sticks, a process akin to “programming” the loom.

During weaving, the weaver (or a mechanism) would cycle through this pattern sequence. Each node acted as a command, precisely controlling which warp threads to lift, thereby revealing the predetermined design through the interlacing of warp and weft.

Beyond the exquisite patterns it produced, the scientific thinking embedded in the figure loom is even more remarkable.

If the loom’s operation is represented in code – where a raised warp thread (over the weft) signifies 1 and a lowered one signifies 0 – the entire fabric pattern transforms into a sequence of zeros and ones. This mirrors the binary principle foundational to modern computing.

Remarkably, the programming method for the Laoguan Han tomb loom model was not singular; it employed at least two distinct techniques – sliding frames and connecting rods – each generating different patterns.

Subsequently, China’s figure loom technology spread westward along the Silk Road. Persian merchants introduced it to the West in the 6th century. By the 12th century, silk-weaving workshops using Chinese-style looms had emerged in cities such as Lucca and Venice, Italy.

The sophisticated silk-weaving machine made use of programmable computation, prompting CAST to describe it as an early form of computer. Photo: China Silk Museum

In 1805, French craftsman Joseph Marie Jacquard created an automatic pattern-weaving loom controlled by punched cards and needles, which gave rise to its western name “Jacquard loom”.

Karl Marx noted in Capital that “before the invention of the steam engine, the Jacquard loom was the most complex machine,” and its automation concepts provided key inspiration for the European Industrial Revolution.

In the 19th century, the punched cards of the automatic figure loom also inspired programming methods for early computers.

“The figure loom is not merely a textile tool but a crystallisation of ancient programming thought and mechanical wisdom,” stated Wang Yusheng, former director of the China Science and Technology Museum, in a February 2025 article for China Science Communication.

“It made Chinese silk a global luxury, shaping the cultural identity of the ‘Silk Nation,’ while its technological logic profoundly influenced the foundational principles of modern information technology.”

In 1946, a significant milestone in computing was reached with the completion of the world’s first general-purpose electronic computer, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), by a team at the University of Pennsylvania.

A core member of that team was Zhu Chuanju, credited with designing parts of the computer’s logical structure. His work applied binary and programming concepts, which some scholars have traced back to ancient Chinese innovations like the figure loom and the binary-inspired philosophy of the text “I Ching”. |