trump does not seem to like the foreign policy space he finds himself in the arena

noted that bolton was let go

waiting to see who takes his place

policy changes I doubt

for the embedded deep-state is deep and anyone picked from the deep would be deep

2020 should be very interesting

in the mean time, capital war enhanced to the next level

as more fronts are opened on war, more existing structures would be tee-ed up for creative destruction, which at times inconvenient in detailing and timing

There is apparently a. school of thoughts that that whilst trade wars are not so easy to win, capital wars are

Below direction is very bullish ... for gold.

I hope the investors on one side and speculators on the other are ready for the sacrifice asked but not explained to them.

bloomberg.com

Forget Trade Wars. Capital Wars Are Easier to Win.

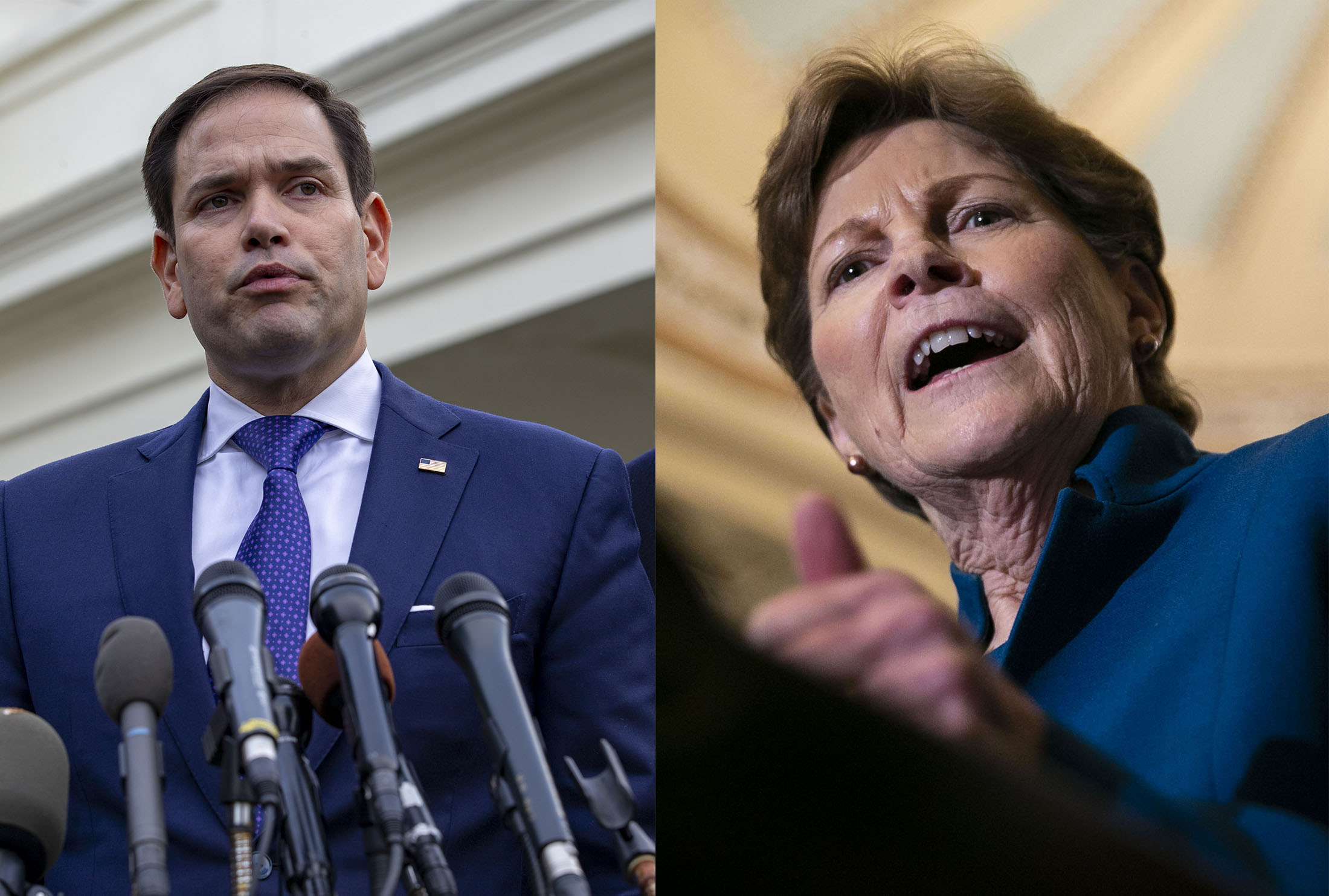

An effort by Senators Marco Rubio and Jeanne Shaheen to steer pension investments away from China could have damaging repercussions.

John Authers

September 10, 2019, 10:30 PM GMT+8

Rubio and Shaheen understand that the road to limiting capital flows to China lies through indexes.

Photographers: Al Drago & Sarah Silbiger/Bloomberg

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

Read more opinion

Trade wars, we are now learning, aren’t easy to win. But there is far more to globalization than trade in goods, and there are many more ways to hurt an economic adversary than with tariffs.

These days, flows of capital matter at least as much as flows of goods. In fact, capital protectionism might pose a far greater threat to China, or to any other economic competitor, than trade protectionism. On Tuesday, China made it clear just how important overseas funds are to its growth and stability by announcing the removal of a decades-old hurdle to foreign investment. Many Western investors had long hoped for just such a development.

But frenzied innovation by the financial-services industry, designed to help money move between countries as cheaply and easily as possible, has also made it far easier to block off that flow. So it may be that this year’s most important and dangerous move in the escalating conflict between the U.S. and China may not have come from any presidential tweet on tariffs, but rather with a letter Senators Marco Rubio and Jeanne Shaheen sent last month to Michael Kennedy, chairman of the group that oversees the federal government’s main retirement savings fund.

Advertisement

Scroll to continue with content

Rubio, a Florida Republican, and Shaheen, a Democrat from New Hampshire, urged the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board not to go forward with a plan to redirect part of its portfolio so it tracks a widely followed investment index that includes some Chinese companies. The senators complained that the decision to mirror the gauge — the MSCI All-Country World excluding the U.S. index — “will effectively use these retirement savings to fund the Chinese government and Communist Party’s efforts to undermine U.S. economic and national security.” They also cite other concerns, including lack of transparency and the potential for fraud among Chinese-listed firms, saying the investment change will expose some $50 billion in retirement assets to material risks.

This is a bipartisan action from two senators nearer to the center of American politics than the extremes. Rubio and Shaheen are both serious and respected figures in the Senate, and neither is regarded as an ideologue. Their initiative is easily explained and asks little or no sacrifice from voters — unlike the tariff conflict, which could soon start to be very painful for American consumers. But in the longer term, their action, if enacted, might inflict damage on the global capitalist system that is just as severe.

The senators’ investment appeal takes advantage of a key choke point in the financial system having to do with the key role that indexes now play in the world of investment. Just as they delegated the hard work of deciding creditworthiness to the ratings agencies a decade ago, banks and financial institutions have largely left it to the big indexing organizations to decide which countries are and aren’t worthy of investment. The indexing industry itself is increasingly concentrated, with Bloomberg LP itself playing an increasing role, particularly in bond and commodity indexes. When it comes to emerging markets, MSCI, a New York-based public company with a market value of $20 billion, is by far the most influential.

Rubio and Shaheen evidently understand that the road to controlling and limiting flows of capital to China lies through the indexing groups. A little pressure could easily go a long way.

At present, both active and passive managers in emerging markets are effectively guided by MSCI’s benchmarks, which now include Chinese stocks. Investing in global or emerging markets funds automatically means buying Chinese shares. However, and crucially, MSCI and the other index groups also make it cheap and easy to exclude China. Indexing groups are already accustomed to offering benchmarks that exclude high-carbon emitters, companies with dubious governance and so on. Coming up with benchmarks that exclude China, or even U.S. and European companies with extensive business in China, is easily done.

A generation ago, when students demanded that their universities divested from apartheid-era South Africa, they were asking investment officers to embark on a difficult technical task. Now, excluding China would be child’s play by comparison. If enough Americans decide they want to deny equity capital to China, it can largely happen. For example, there is already an exchange-traded fund that tracks the emerging markets without China, which has a barely a thousandth of the assets than are in the flagship emerging markets ETF. For pension trustees under pressure, acceding to the senators’ demands would involve switching from one ETF to another. Nothing more.

Is this healthy? It may not be, for two reasons. The first is that sanctions need not only apply to government-run pension funds. They can easily be imposed by individuals. If the idea of divesting from China gains momentum, and it has bipartisan support, students and pension members could soon start applying pressure of their own. Divestment of apartheid-era South Africa and the current campaign for large investors to divest from fossil fuels provide templates. Herein lies a way for governments to lose control of the most highly sensitive relationship in the global economy. If the U.S. wants to kiss, make up and make a deal, it will find this harder if China is being hit by a divestment campaign.

Second, there is the issue of whether this is the way capitalism is supposed to work. It is popular now to argue that pension funds should think about the long-term interest of their clients when they invest; this may not always mean maximizing returns. For example, retirees need clear air to breathe when they retire. They also arguably need a China that doesn’t steal jobs and intellectual property from the U.S. There is sense in this, but also the danger that allocating capital will degenerate into a fight between different political priorities. If pensions, endowments, sovereign wealth funds and other forms of long-term capital are turned into political vehicles, then earning a return, and allocating capital to where it can be best used, will grow far harder.

Rubio and Shaheen are advocating the use of a blunt instrument to advance aims that may be better pursued through normal diplomatic channels. It should be used with care.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

John Authers at jauthers@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net |