Julius

thank you

youtube.com

What happens if a coronavirus vaccine is never developed? It has happened before

By Rob Picheta, CNN

Updated 0733 GMT (1533 HKT) May 4, 2020

London (CNN)As countries lie frozen in lockdown and billions of people lose their livelihoods, public figures are teasing a breakthrough that would mark the end of the crippling coronavirus pandemic: a vaccine.

But there is another, worst-case possibility: that no vaccine is ever developed. In this outcome, the public's hopes are repeatedly raised and then dashed, as various proposed solutions fall before the final hurdle.

Instead of wiping out Covid-19, societies may instead learn to live with it. Cities would slowly open and some freedoms will be returned, but on a short leash, if experts' recommendations are followed. Testing and physical tracing will become part of our lives in the short term, but in many countries, an abrupt instruction to self-isolate could come at any time. Treatments may be developed -- but outbreaks of the disease could still occur each year, and the global death toll would continue to tick upwards.

It's a path rarely publicly countenanced by politicians, who are speaking optimistically about human trials already underway to find a vaccine. But the possibility is taken very seriously by many experts -- because it's happened before. Several times.

"There are some viruses that we still do not have vaccines against," says Dr. David Nabarro, a professor of global health at Imperial College London, who also serves as a special envoy to the World Health Organization on Covid-19. "We can't make an absolute assumption that a vaccine will appear at all, or if it does appear, whether it will pass all the tests of efficacy and safety.

The timetable for a coronavirus vaccine is 18 months. Experts say that's risky

"It's absolutely essential that all societies everywhere get themselves into a position where they are able to defend against the coronavirus as a constant threat, and to be able to go about social life and economic activity with the virus in our midst," Nabarro tells CNN.

Most experts remain confident that a Covid-19 vaccine will eventually be developed; in part because, unlike previous diseases like HIV and malaria, the coronavirus does not mutate rapidly.

Many, including National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony Fauci, suggest it could happen in a year to 18 months. Other figures, like England's Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty, have veered towards the more distant end of the spectrum, suggesting that a year may be too soon.

But even if a vaccine is developed, bringing it to fruition in any of those timeframes would be a feat never achieved before.

"We've never accelerated a vaccine in a year to 18 months," Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, tells CNN. "It doesn't mean it's impossible, but it will be quite a heroic achievement.

"We need plan A, and a plan B," he says.

When vaccines don't work

In 1984, the US Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler announced at a press conference in Washington, DC, that scientists had successfully identified the virus that later became known as HIV -- and predicted that a preventative vaccine would be ready for testing in two years.

Nearly four decades and 32 million deaths later, the world is still waiting for an HIV vaccine.

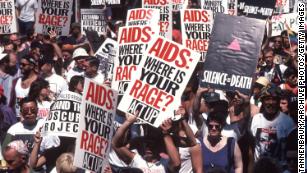

Instead of a breakthrough, Heckler's claim was followed by the loss of much of a generation of gay men and the painful shunning of their community in Western countries. For many years, a positive diagnosis was not only a death sentence; it ensured a person would spend their final months abandoned by their communities, while doctors debated in medical journals whether HIV patients were even worth saving.

Protester Mark Milano is arrested during an AIDS demonstration in Washington DC in 1994.

The search didn't end in the 1980s. In 1997, President Bill Clinton challenged the US to come up with a vaccine within a decade. Fourteen years ago, scientists said we were still about 10 years away.

The difficulties in finding a vaccine began with the very nature of HIV/AIDS itself. "Influenza is able to change itself from one year to the next so the natural infection or immunization the previous year doesn't infect you the following year. HIV does that during a single infection," explains Paul Offit, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist who co-invented the rotavirus vaccine.

"It continues to mutate in you, so it's like you're infected with a thousand different HIV strands," Offit tells CNN. "(And) while it is mutating, it's also crippling your immune system."

HIV poses very unique difficulties and Covid-19 does not possess its level of elusiveness, making experts generally more optimistic about finding a vaccine.

Lessons the AIDS epidemic has for coronavirus

But there have been other diseases that have confounded both scientists and the human body. An effective vaccine for dengue fever, which infects as many as 400,000 people a year according to the WHO, has eluded doctors for decades. In 2017, a large-scale effort to find one was suspended after it was found to worsen the symptoms of the disease.

Similarly, it's been very difficult to develop vaccines for the common rhinoviruses and adenoviruses -- which, like coronaviruses, can cause cold symptoms. There's just one vaccine to prevent two strains of adenovirus, and it's not commercially available.

"You have high hopes, and then your hopes are dashed," says Nabarro, describing the slow and painful process of developing a vaccine. "We're dealing with biological systems, we're not dealing with mechanical systems. It really depends so much on how the body reacts."

Human trials are already underway at Oxford University in England for a coronavirus vaccine made from a chimpanzee virus, and in the US for a different vaccine, produced by Moderna.

However, it is the testing process -- not the development -- that holds up and often scuppers the production of vaccines, adds Hotez, who worked on a vaccine to protect against SARS. "The hard part is showing you can prove that it works and it's safe."

Plan B

If the same fate befalls a Covid-19 vaccine, the virus could remain with us for many years. But the medical response to HIV/AIDS still provides a framework for living with a disease we can't stamp out.

"In HIV, we've been able to make that a chronic disease with antivirals. We've done what we've always hoped to do with cancer," Offit says. "It's not the death sentence it was in the 1980s."

The groundbreaking development of a daily preventative pill -- pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP -- has since led to hundreds of thousands of people at risk of contracting HIV being protected from the disease.

A number of treatments are likewise being tested for Covid-19, as scientists hunt for a Plan B in parallel to the ongoing vaccine trials, but all of those trials are in very early stages. Scientists are looking at experimental anti-Ebola drug remdesivir, while blood plasma treatments are also being explored. Hydroxychloroquine, touted as a potential "game changer" by US President Donald Trump, has been found not to work on very sick patients.

"The drugs they've chosen are the best candidates," says Keith Neal, Emeritus Professor in the Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases at the University of Nottingham. The problem, he says, has been the "piecemeal approach" to testing them.

Remdesivir, one of the drugs being tested as a Covid-19 treatment.

"We have to do randomized controlled trials. It's ridiculous that only recently have we managed to get that off the ground," Neal, who reviews such tests for inclusion in medical journals, tells CNN. "The papers that I'm getting to look at -- I'm just rejecting them on the grounds that they're not properly done."

Now those fuller trials are off the ground, and if one of those drugs works for Covid-19 the signs should emerge "within weeks," says Neal. The first may already have arrived; the US Food and Drug Administration told CNN it is in talks to make remdesivir available to patients after positive signs it could speed up recovery from the coronavirus.

The knock-on effects of a successful treatment would be felt widely; if a drug can decrease a patient's average time spent in ICU even by by a few days, it would free up hospital capacity and could therefore greatly increase the willingness of governments to open up society.

But how effective a treatment is would depend on which one works -- remdesivir is not in high supply internationally and scaling up its production would cause problems.

And crucially, any treatment won't prevent infections occurring in society -- meaning the coronavirus would be easier to manage and the pandemic would subside, but the disease could be with us many years into the future.

What life without a vaccine looks like

If a vaccine can't be produced, life will not remain as it is now. It just might not go back to normal quickly.

"The lockdown is not sustainable economically, and possibly not politically," says Neal. "So we need other things to control it."

That means that, as countries start to creep out of their paralyses, experts would push governments to implement an awkward new way of living and interacting to buy the world time in the months, years or decades until Covid-19 can be eliminated by a vaccine.

"It is absolutely essential to work on being Covid-ready," Nabarro says. He calls for a new "social contract" in which citizens in every country, while starting to go about their normal lives, take personal responsibility to self-isolate if they show symptoms or come into contact with a potential Covid-19 case.

Social distancing and lockdowns could be reintroduced until a vaccine is found.

It means the culture of shrugging off a cough or light cold symptoms and trudging into work should be over. Experts also predict a permanent change in attitudes towards remote working, with working from home, at least on some days, becoming a standard way of life for white collar employees. Companies would be expected to shift their rotas so that offices are never full unnecessarily.

"It (must) become a way of behaving that we all ascribe to personal responsibility ... treating those who are isolated as heroes rather than pariahs," says Nabarro. "A collective pact for survival and well-being in the face of the threat of the virus.

"It's going to be difficult to do in poorer nations," he adds, so finding ways to support developing countries will become "particularly politically tricky, but also very important." He cites tightly packed refugee and migrant settlements as areas of especially high concern.

In the short term, Nabarro says a vast program of testing and contact tracing would need to be implemented to allow life to function alongside Covid-19 -- one which dwarfs any such program ever established to fight an outbreak, and which remains some time away in major countries like the US and the UK.

"Absolutely critical is going to be having a public health system in place that includes contact tracing, diagnosis in the workplace, monitoring for syndromic surveillance, early communication on whether we have to re-implement social distancing," adds Hotez. "It's doable, but it's complicated and we really haven't done it before."

America's 'new normal' will be anything but ordinary

Those systems could allow for some social interactions to return. "If there's minimal transmission, it may indeed be possible to open things up for sporting events" and other large gatherings, says Hotez -- but such a move would not be permanent and would continually be assessed by governments and public health bodies.

That means the the Premier League, NFL and other mass events could go ahead with their schedules as long as athletes are getting regularly tested, and welcome in fans for weeks at a time -- perhaps separated within the stands -- before quickly shutting stadiums if the threat rises.

"Bars and pubs are probably last on the list as well, because they are overcrowded," suggests Neal. "They could reopen as restaurants, with social distancing." Some European countries have signaled they will start allowing restaurants to serve customers at vastly reduced capacity.

Restrictions are most likely to come back over the winter, with Hotez suggesting that Covid-19 peaks could occur every winter until a vaccine is introduced.

And lockdowns, many of which are in the process of gradually being lifted, could return at any moment. "From time to time there will be outbreaks, movement will be restricted -- and that may apply to parts of a country, or it may even apply to a whole country," Nabarro says.

Related coverage

Oxford partners with pharma giant to develop vaccine Coronavirus is changing some anti-vaxxers' minds Wuhan shows the world that normal is still some time away

The more time passes, the more imposing becomes the hotly debated prospect of herd immunity -- reached when the majority of a given population, around 70% to 90%, becomes immune to an infectious disease. "That does to some extent limit spread," Offit says -- "although population immunity caused by natural infection is not the best way to provide population immunity. The best way is with a vaccine."

Measles is the "perfect example," says Offit -- before vaccines became widespread, "every year 2 to 3 million people would get measles, and that would be true here too." In other words, the amount of death and suffering from Covid-19 would be vast even if a large portion of the population is not susceptible.

All of these predictions are tempered by a general belief that a vaccine will, eventually, be developed. "I do think there'll be vaccine -- there's plenty of money, there's plenty of interest and the target is clear," Offit says.

But if previous outbreaks have proven anything, it's that hunts for vaccines are unpredictable. "I don't think any vaccine has been developed quickly," Offit cautions. "I'd be really amazed if we had something in 18 months." |