Like you, Joe Carson has a very LT good track record, in his areas of expertise.

All the best to you & your family,

Iso

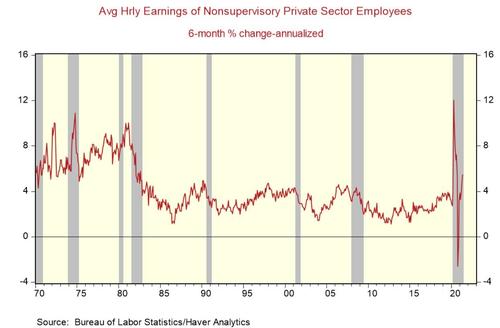

1. <Accelerating Wages Early In the Upturn Resemble the Business Cycles of the 1970s

thecarsonreport.com

Investors and businesses viewed the recent jobs and wage data differently. Investors saw the below-consensus gain in employment as friendly to risk-based assets. Companies would counter, saying it took three times the consensus gain (0.6%) in average hourly earnings, and probably other compensation-sweeteners, to attract the 559,000 workers in May.

Rising wages so early in a business cycle resemble the US economy of the 1970s, not the one investors and policymakers have seen since 1980. Rising labor costs will continue to put downward pressure on firms operating margins, which have already declined for the past two quarters, and add to general inflation pressures that policymakers would soon discover are not "transitory." Investors and policymakers forewarned.

Evidence of A Fast Wage Cycle

In May, average hourly earnings for private-sector workers, excluding supervisory staff, rose 0.6%, three faster than consensus estimates. That comes on the heels of an even more significant 0.8% increase in April. That two-month increase is the fastest in this wage series since 1983 (excluding the wage distortions during the pandemic).

More importantly, it extends the rising wage cycle that has been quickly emerging for several months and runs counter to the early cycle decelerating wage pattern that has been a recurring feature for the past 40 years.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has yet to date the end of the 2020 recession. Based on a long list of economic data, it's reasonable to conclude that the recession's end occurred in late 2020.

Comparing the wage data of the past six months shows a close resemblance to the 1970 economic cycles and not the business cycles the current generation of policymakers and investors has grown accustomed to seeing.

In the 1970s, wage growth started to accelerate immediately when the economy began to recover, similar to what is happening nowadays. Each period has unique features, but the common themes are the lack of labor supply and the need to raise pay to attract workers.

Both episodes contrast to the wage pattern that emerged in the four economic upturns from 1980 to 2020. In each of the four economic upturns since 1980, wage gains for private-sector workers decelerated for several years, enabling companies to source cheap labor and expand profit margins. Part of that deceleration also reflects the shift in hiring from relatively higher-paid to lower-paid workers.

Yet, in the past six months, over one-third of new jobs were created in the lower-paid industries (i.e., leisure and hospitality), and average hourly earnings growth still accelerated to its fastest rate since 1983.

Once started, wage cycles gain momentum of their own. Faced with a shrinking supply of skilled and unskilled labor, companies start competing with each other. And employed workers, along with people sitting on the sidelines, become well aware of the more worker-friendly environment and use it as leverage to gain more pay and benefits.

Record job vacancies say the wage cycle has a long life ahead and is not "transitory" or temporary.

2. <Record Lead-Times For Materials Signal Firms Are Expecting Persistent Inflation

thecarsonreport.com

In May, the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) reported that lead time for production materials jumped to 85 days, up from 79 in April. The May reading is an entire work-day month (21 days) above the level from one year ago and the highest reading since 1979, or when ISM has been using the current methodology to track lead times.

Lead times are a valuable indicator of current and future demand. When backlogs rise and get stretched out, firms protect their production schedules by building safety stocks and placing long-dated orders for materials and supplies to meet expected future demand.

The current generation of policymakers probably does not follow lead times, but the old generation did. (Read the 1994 transcripts of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings). Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan religiously tracked lead times, order backlogs, and delayed deliveries (i.e., vendor performance or nowadays called supplier delivery index) as signs of future inflation and inventory building. The latter is an essential part of demand-driven fast growth and inflation cycles since it adds a layer of demand, putting more pressure on prices.

In May, a record low 28% reading for the customer inventories index and a relatively high price index reading of 88% accompanied the record high reading for lead times. The old generation of policymakers would see these data points as evidence of a more general emergence of inflation pressures.

It would be prudent for the current generation of policymakers to scrap their "transitory" price playbook and take out the policy playbook of 1994.

In 1994, with a set of lead time, suppliers index, and price paid data that is not as scary as today, the old generation of policymakers saw the need for substantial monetary restraint to break the inflation cycle and limit the cyclical rise in general inflation. When the monetary tightening cycle was over 12 months later, the old generation raised the nominal and real federal funds rate 300 basis points. Years later, Mr. Greenspan praised his team's decisions as it successfully cut short the inflation cycle.

The current generation is not even thinking about lifting official rates, and even if they decided to so tomorrow, there is a gradual progression of effects on the economy. So if policymakers decided to raise the official rates to pre-pandemic levels of 1.5% over several quarters, the full impact would not be felt for a year or more. Even that would not impose much monetary restraint as it would still leave real interest rates negative.

As such, the current generation of policymakers is running with a policy approach--doing nothing--- that has never even been used to break an inflation cycle. In the past, delays in enacting monetary restraint triggered bad outcomes, so the odds of a successful outcome from a doing nothing policy approach seem very low, probably as low as the federal funds rate (0.06%).

|