speaking of gaming,

bloomberg.com

Trump Is Driving Off Investors and Threatening the Dollar’s Reign

The president’s economic agenda is dragging down the dollar and making it more difficult for the US to finance its deficits.

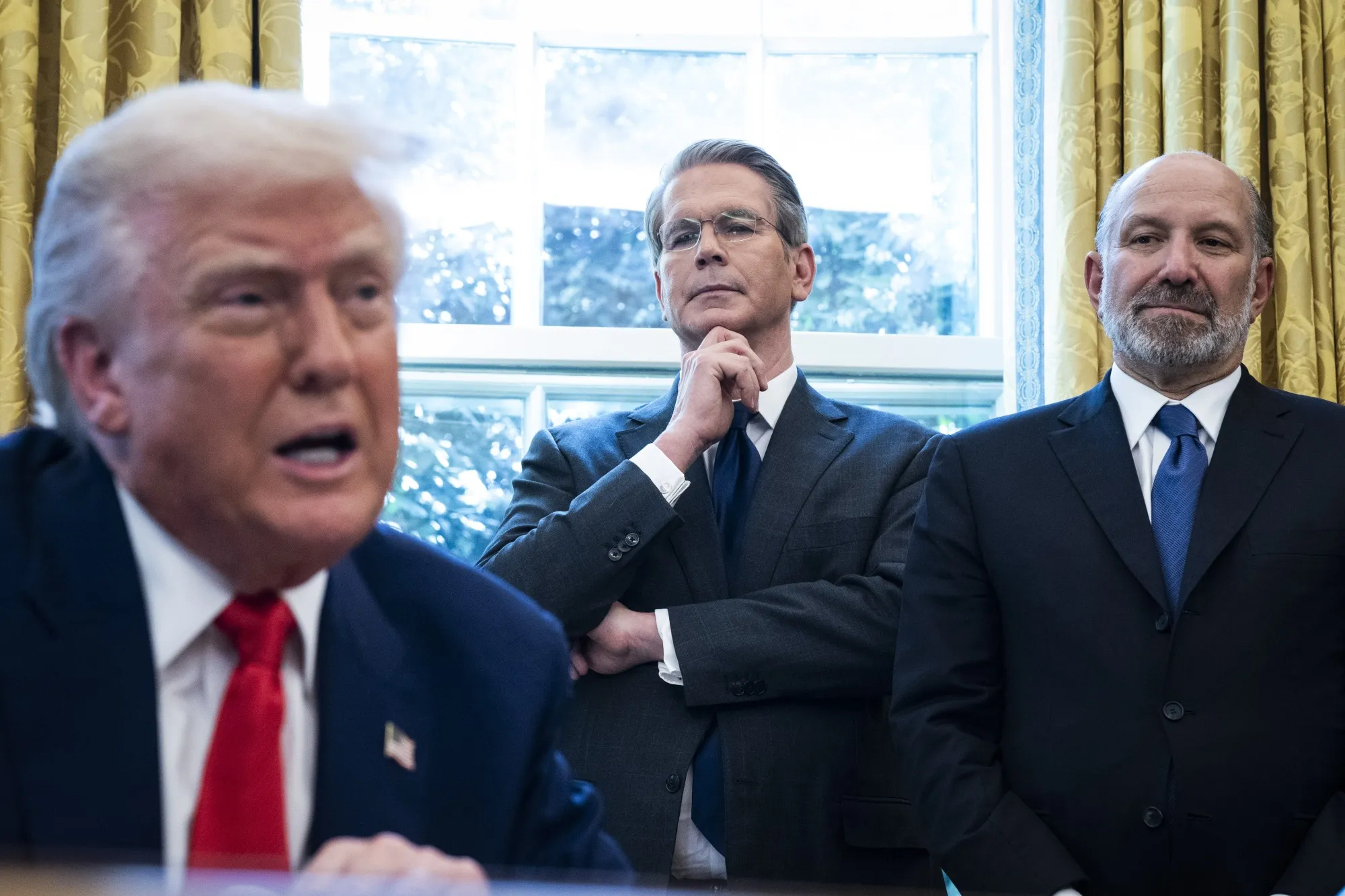

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick listen to President Donald Trump.

Photographer: Jabin Botsford/Getty Images

By Carter Johnson, Saleha Mohsin, and Ruth Carson

June 18, 2025 at 7:35 AM GMT+8

- The US dollar has lost over 10% of its value against the euro, pound, and Swiss franc since President Donald Trump took office, and is down against every major currency.

- The Trump administration's policies, including tariff hikes, tax cuts, and pressure on the Federal Reserve, are driving investors away and contributing to the dollar's decline.

- The dollar's fall could lead to a vicious cycle of dollar and deficit concerns, prompting foreigners to repatriate their money, driving up borrowing costs, and compounding fiscal woes.

Summary by Bloomberg AI

There is no better barometer of global investors’ repudiation of President Donald Trump’s policies than the dollar. Since he took office, it’s lost more than 10% of its value against the euro, pound and Swiss franc and is down against every single major currency in the world.

The last time the dollar plunged this much, this fast was in 2010, when the Federal Reserve was frantically printing money to prop up the economy in the wake of the financial crisis. This time, it’s several of the key pillars of the Trump agenda that are driving investors away: the across-the-board tariff hikes that shocked allies and upended trade; the push to ram through tax cuts that would add to bloated deficits and debt; the pressure campaign to get the Fed to slash interest rates; and the bare-knuckled legal tactics employed against those who oppose his policies.

A screen displaying the rate of the yen against the US dollar.

Photographer: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg

What’s surprising to long-time market observers is the Trump team’s seeming indifference to the dollar’s plunge. Sure, they’ll state their support for a “strong dollar” when asked by reporters and lawmakers, as their predecessors have for decades, but they’re doing little to try to halt its decline. If anything, there’s a sense among traders that the administration wants to keep devaluing the dollar to buoy US manufacturing — even sparking chatter at one point that it’s making exchange-rate levels part of tariff negotiations with trading partners. Right or wrong, that speculation is causing wild swings in the dollar, like when it crashed 4% against the Taiwan dollar in just over an hour last month.

This is a dangerous game: The government’s annual financing needs have skyrocketed to over $4 trillion after years of runaway budget deficits. Much of that financing comes from foreign creditors, and the more the dollar sinks, the bigger the losses they suffer when converting their investments back into their local currencies.

“Trump is definitely playing with fire,“ says Stephen Miller, a consultant for GSFM, a unit of Canada’s CI Financial Corp. in Australia.

At some point, if things get bad enough, a sort of vicious cycle could kick in. Dollar and deficit concerns prompt foreigners to repatriate their money, which drives up borrowing costs and compounds both the dollar declines and fiscal woes, which then in turn heighten these worries and so on and so on.

Few are predicting that will actually happen — the US has always found ways to pull itself out of financial holes in the past — and yet few are willing to rule it out either. It’s the sort of risk that has long tormented finance officials in developing nations across the world. But for the US, the pre-eminent global power and proprietor of the world’s most-coveted currency, it’s a new financial reality that hasn’t quite sunk in.

Miller, who used to run Australian fixed-income markets for BlackRock Inc., is among those who suspect the Trump administration, or at least factions of it, may indeed be rooting for a weaker dollar. “They might be very, very successful in doing it, but that could be very, very uncomfortable” — to the point, he says, that they “lose control of that process.”

He’s touting gold, which has rallied this year, as an alternative to the dollar. So too is Jeffrey Gundlach, CEO of DoubleLine Capital. Gundlach is particularly concerned about the soaring US interest tab and how it’s amplifying the deficit. “The reckoning is coming,” he told a Bloomberg conference last week. A day earlier, Paul Tudor Jones, one of the pioneers of macro-hedge fund investing, predictedthe US fiscal woes would drag the dollar down another 10% over the next 12 months.

Investors Are Reconsidering Dollar's Value Under TrumpGreenback hit by blitz of tariff rollouts and pauses

Source: Bloomberg

Note: Date markers are approximate.

The Jones call is an extreme example of an increasingly popular view on Wall Street. The consensus analyst forecast is now for the dollar to steadily fall against the euro, yen, pound, Swiss franc, Canadian dollar and Australian dollar over the next several years. Among the most bearish: Morgan Stanley, which says the greenback will tumble to levels last seen during the Covid-19 pandemic by next year, and Goldman Sachs, which estimates it’s 15% overvalued.

In the futures market, the bets against the dollar began to pour in from the moment Trump took office in January.

By March, the wagers had grown so large that hedge funds and other investors had amassed their first net bearish position on the dollar in six months, according to CFTC data, and by mid-June, that position had swelled to $15.9 billion. On Tuesday, Bank of America released a survey showing global fund managers are more underweight the dollar now than at any point in the past 20 years.

Derivatives Traders Are Now Bearish on the DollarAggregate net short totals around $15.9 billion in most recent data

Source: Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Bloomberg

Note: Data includes net futures positions recorded by CFTC through June 10, 2025

Doubts about the dollar’s hegemony are nothing new, of course. Ever since it was anointed the world’s reserve currency in the aftermath of WWII, bouts of angst have emerged from time to time. There’s a resilience to the US economy, though, that has always brought the dollar back.

Besides, there are no obvious candidates to supplant it — all the other major currencies have problems of their own — and so dollar outflows typically peter out at some point. “The question is, what do you own?” said Daniel Murray, deputy CIO of EFG International in Zurich. “It’s tough because there are not really any other markets out there that are sufficiently deep and broad.”

And for all the concern that the dollar is losing its status as a safe-haven asset under Trump, it’s rallied the past few days, albeit tepidly, after Israel launched an attack on Iran that threatens to roil the Middle East and snarl oil markets.

The dollar has been mostly stable — as have Treasury bond yields — since the Trump tariff rollout sparked a three-week rout in April that lopped 4% off its value. And the dollar is still stronger today, when measured against most major currencies, than it was when Trump left office back in 2021. When asked whether the administration was concerned about the dollar’s recent declines, a Treasury spokesperson pointed to this historical context, noting it’s stronger today than it’s been on average over the past four decades.

Currency traders work near a screen showing the foreign exchange rate between U.S. dollar and South Korean won.

Photographer: Ahn Young-joon/AP

This could explain some of the nonchalance coming from the administration. For years, Trump and his inner circle advocated for a weaker dollar to help manufacturers compete against cheap imports and hire more factory workers at home.

And while he’s been quiet on that topic since returning to the White House, many believe it continues to shape his thinking on the dollar. They point to the administration’s decision not to quickly address speculation last month that it was pushing for a weaker dollar as part of the tariff negotiations with Taiwan and South Korea. That chatter had sent the dollar cratering against both currencies, fueling a broader selloff across Asia and deepening its losses this year. “The message is subtle but clear: Dollar strength is now negotiable,” said Haris Khurshid, chief investment officer at Karobaar Capital in Chicago.

Days after the selloffs, Stephen Miran, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, did push back on the speculation when asked on Bloomberg’s Big Take DC podcast, saying there was no such US policy.

President Donald Trump holds a document from the Office of the United States Trade Representative during a tariff announcement.

Photographer: Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA

Then there’s the “revenge” tax, as Section 899 of the Trump tax bill wending its way through Congress has become known. Surrounded by page after page of tax cut provisions for American workers and companies, it’d increase the income tax rate on investors based in foreign countries with policies the US deems discriminatory. Its inclusion further underscores how little concern there is within the administration about driving away global investors.

This is what worries Miller, the consultant with GSFM in Australia. When he talks about how Trump is “playing with fire,” it’s because a seemingly painless, gradual currency decline can quickly turn into a rout in a country as dependent on overseas financing as the US is. “You’re increasingly relying on the kindness of foreign investors now,” Miller said.

Trump’s tax bill, in its current state, would only add to those financing needs. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates the version passed by the lower house would tack nearly $3 trillion onto US deficits over the next decade.

Even if the tax bill were rejected, the government’s finances look precarious. The budget deficit has swelled to more than 6% of gross domestic product the past couple years, the largest on record excluding times of war or steep economic downturn. And the government’s debt pile has soared to $29 trillion, equal to almost 100% of GDP. A decade ago, that number was 72%.

In May, the US lost its last AAA credit rating when Moody’s Ratings downgraded it, citing the ballooning deficits.

Weeks earlier, investors carried out a downgrade of sorts themselves. As Trump was rolling out his tariff plan, they started treating Treasury bonds — long considered the risk-free benchmark on Wall Street — like risky assets, selling (and buying) them in tandem with stocks.

The traditional correlation between Treasuries and the dollar broke down, too. As Treasury yields rose, the dollar fell. For years, the opposite had been true: rising rates lured investors to the world’s reserve currency, pushing it higher.

Now, though, with the US increasingly isolated internationally and sinking ever deeper in debt, a very different dynamic seemed to be taking hold: Investors were selling Treasuries, pushing up yields, and then yanking their money out of the country. The dollar-and-bonds correlation remains inverted today.

Leah Traub, a partner and portfolio manager on the global rates team at Lord Abbett, says there’s a self-reinforcing quality to the whole thing. As global investors start to diversify away from the dollar, they drive its value down, which only further underscores the benefits of such a strategy. And once that happens, Taub says, “it’s really hard to put the cat back in the bag.”

— With assistance from Ye Xie and Greg Ritchie |