re <<prize>>

bloomberg.com

China Is Run by Engineers, and the US by Too Many Lawyers

In his new book, Dan Wang argues that America is too good at making rules, and could learn from Beijing’s laser focus on technical innovation.

Photo Illustration: Chantal Jahchan for Bloomberg; Wang by Silvia Lindtner; courtesy (3)

By Christopher Beam

August 15, 2025 at 2:00 PM GMT+8

Corrected

August 15, 2025 at 4:46 PM GMT+8

When Dan Wang first heard President Donald Trump describe the date for imposing tariffs on US trade partners as “Liberation Day,” the phrase caught his ear. “‘Liberation’ is not a very American word,” he told me recently. “It’s much more of a Chinese word.”

Wang would know. For years, as a China-based analyst for a macro research firm, he pored over speeches and official documents of the Chinese Communist Party, trying to extract meaning from jargon.

Wang now sees parallels between Trump and President Xi Jinping, he says: the blind loyalty of their base, the demonization of foreigners and a willingness to foment unease among immigrants and minorities by threatening their status within society. “What we have in the US is authoritarianism without the good stuff,” he says. The good stuff being, according to Wang, things such as high-speed trains, well-functioning cities, and political and economic stability.

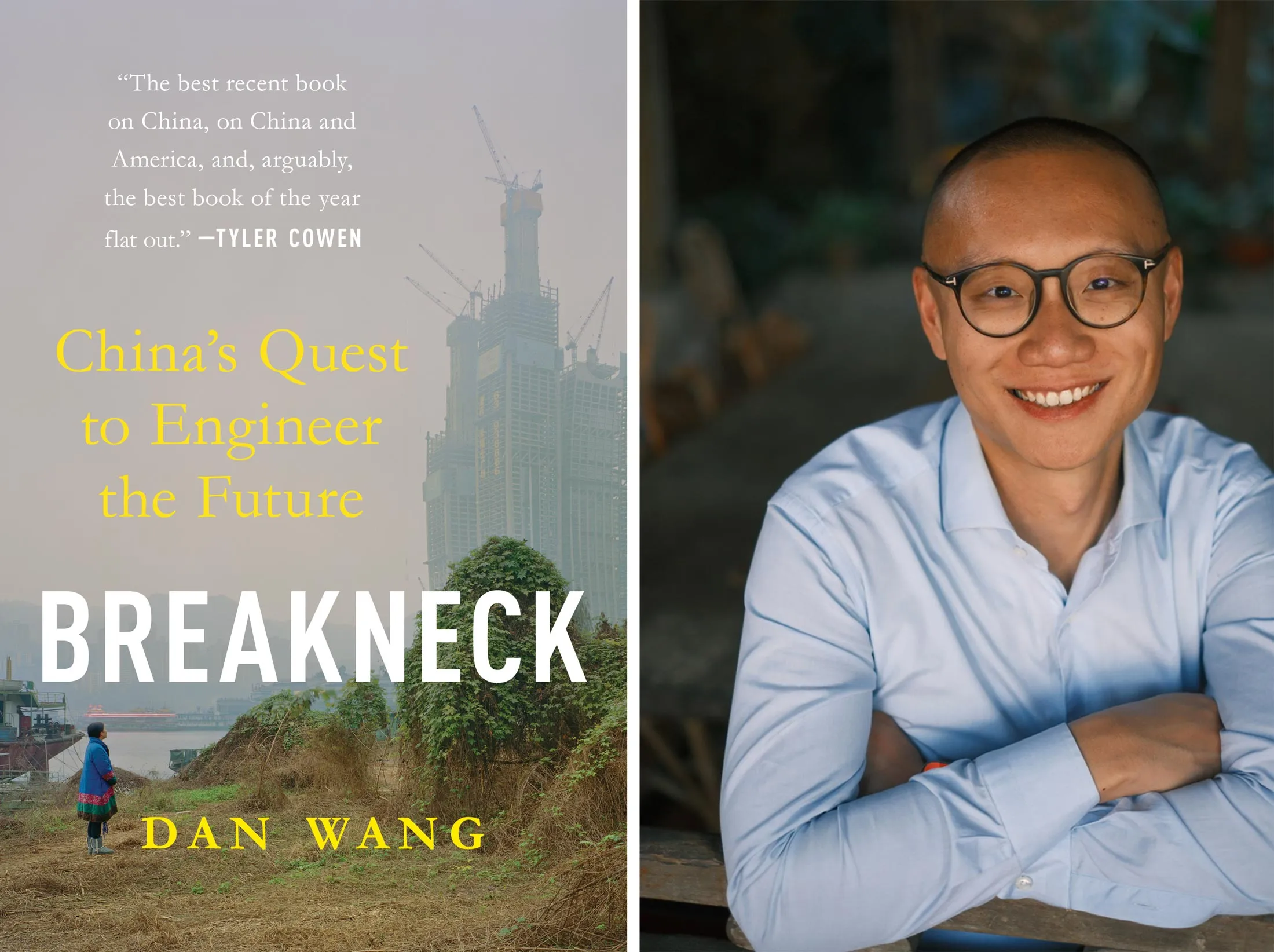

The United States needs to study China if it’s going to remain a superpower, Wang argues in his new book, Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future. But it needs to learn the right lessons — including, most importantly, how to build.

In Breakneck, Wang argues that the key difference between the two giants is that China is run by engineers — in 2002 all nine members of the Politburo standing committee had engineering backgrounds — whereas the US is run by lawyers. China prioritizes building colossal public works such as bridges, dams and airports, as well as products like toys and iPhones. The US excels at making and enforcing rules.

This was a good thing during the 1960s and ’70s, when lawyers pushed back against the American technocratic regime that had damaged the environment, run highways through urban neighborhoods and gotten the country mired in Vietnam. But now the rulemaking has gone too far, Wang says, and it’s preventing the US from keeping pace with rivals.

Wang says the US needs to study China if it’s going to remain a superpower.

Source: Publisher; Wang by Silvia Lindtner

In this sense, Wang’s argument dovetails with that of Abundance, the recent bestseller by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, which urges US policymakers to cut red tape and boost the supply of housing and transportation. But his book is less of a policy treatise than a tour of what China’s engineering-forward society looks like on the ground — the good (high-speed rail and drones), the bad (one-child and Zero Covid policies) and the ugly (human-rights violations and pointless replicas of European town squares).

If the US is going to outcompete China, Wang suggests, we need to understand it first. That means letting go of simplistic stories peddled by Washington and Silicon Valley. “I think all narratives about China are wrong all the time,” he says. For example, it’s still conventional wisdom in some corners that China can’t innovate but only copy — an absurd charge in the TikTok/DeepSeek/BYD era. He’s similarly unconvinced that China is an unstoppable juggernaut destined to overtake the US as the world’s top power.

Wang rejects familiar categories of China analysis — liberal and conservative, hawk and dove — and resists pat answers (except when it comes to hot pot, which he’s described as “terrible”). His idiosyncratic approach comes from experience. In his book — and in a conversation over Zoom while he was vacationing in Paris — he shows an appreciation for how the vagaries of a political and economic system can shape a country and a life, including his own.

Leaving San Francisco

Wang, who’s just shy of 33, was born in Yunnan province in southwestern China, a region known for its distance from the seat of power — and therefore its relative freedom. His father was a software developer, and his mother worked as a radio and television anchor. He had a blood disease and lung issues as a child, which isolated him from his peers.

In 2000, when Wang was 7, his parents moved the family to Toronto, and two years later to Ottawa. He was enrolled in local public schools and developed eclectic interests: At 15 he enlisted as a Royal Canadian Army Cadet; he also learned clarinet and hoped to play professionally. Wang got a scholarship to the University of Rochester in New York, where he studied philosophy.

There was never a question of following in his father’s engineering footsteps; Wang was bad at math. He dropped out after his junior year to work at Shopify in Toronto in a marketing role and then moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in 2015 to do similar work for Flexport. (He did eventually get his diploma.)

Wang found the Bay Area insular and blinkered. “People were saying San Francisco was the center of the world,” he says. “That didn’t feel right to me.” The transportation system and food scene underwhelmed, and he wasn’t excited about the same technologies that his peers were (crypto, virtual reality and web platforms). He was more intrigued by the kind of hard engineering that was happening in China, such as infrastructure megaprojects, semiconductors and green energy.

Downtown San Francisco in 2015.Photographer: Bloomberg/Bloomberg

So in 2016, Wang moved to Hong Kong to work at the financial analysis firm Gavekal Dragonomics, demystifying China’s politics and economy for investors who wanted to know how they might affect, say, Brazilian soybean prices. The firm “didn’t treat China as just another dataset,” he says; it took a holistic view. He came to see the CCP as an “intellectual puzzle” — a “deeply weird institution” that thinks state control and capitalism are not mutually exclusive.

In 2017 Wang began posting an annual letter to keep up with friends. His interweaving of travelogues, economic analysis and riffs on sci-fi and opera gained a following, including economist Tyler Cowen and tech writer Ben Thompson. In an interview, Cowen, whom Wang considers a mentor, credited Wang’s background as an outsider — a Canadian looking at US politics, a Yunnan native looking at Beijing policy — with shaping his distinct worldview.

Wang moved to mainland China in 2018 to get a closer view of how the system works. He got what he wished for.

‘The World of Atoms’

The Covid-19 pandemic helped crystallize Wang’s idea of the engineering state. He lived in Shanghai during the draconian lockdowns, when people often struggled to get food, workers in all-white protective suits sprayed buildings and megaphones instructed residents to “repress your soul’s yearning for freedom.” The fiasco revealed the downside of treating people like cogs in a piece of machinery. The experience, combined with China’s one-child policy, showed him that the engineering state is “not just about infrastructure, it’s also about population and social engineering,” he says. “That’s the much scarier part.”

After returning to the US in 2023 to accept a fellowship at Yale Law School, Wang was struck by the ambition but also the conformity of the students he met — an observation he connected to University of Michigan professor Nicholas Bagley’s argument that the US government is too procedure-obsessed. Combined, these ideas became the framework of Breakneck.

Wang cooking at a home in the Yunnan city of Dali, where he and his wife stayed for four months.

Source: Dan Wang

Wang tours the successes of the engineering state — from a town that makes guitars to Shenzhen’s nimble ecosystem of tech startups and factories — while recognizing the toll the system takes on individual Chinese, particularly young people, many of whom have fled the cities or the country entirely.

Meanwhile, he exhorts the US to learn to love building again. Anyone looking for policy specifics should look elsewhere, he says; there are think tanks and books focused on how America might reindustrialize. Wang instead calls for the US to take a page from Xi’s playbook and rediscover hard engineering as a proud pursuit, to celebrate “the world of atoms instead of the world of bits.”

He argues that we should rehabilitate Robert Moses, who created some of New York City’s most dynamic infrastructure, and recognize Navy Admiral Hyman Rickover, who launched the first nuclear-powered submarine. And if the Randian romance of bridges and skyscrapers doesn’t inspire, a strong manufacturing base is essential to military advantage. It doesn’t matter how many apps the US designs — or even tools for AI warfare — if it runs out of missiles.

What are the odds that the US maintains its dominance? Wang is surprisingly sanguine. He points to China’s debt burden, its aging population and the government’s fear of its own people as problems that, he predicts, will prevent it from surpassing the US. Meanwhile, he argues that the US is in a strong position to win the long game — if it recommits to building.

That’s a big if, and it’s looking bigger every day. The US is already falling behind China on research in key fields such as renewable energy, quantum mechanics and nuclear power. The gaps in this and other strategic areas only threaten to widen as the second Trump administration undermines the country’s competitiveness by imposing tariffs, cutting funding for science and driving immigrants away. Wang calls US export controls on goods sent to China “the worst of all worlds: They’ve scotched the snake, to quote Macbeth, not killed it.” And Elon Musk, America’s best candidate for a modern Robert Moses, has fallen out with the White House.

Given that the US is running away from Wang’s prescription, Breakneck reads as a warning. The book’s title seems to refer to China’s speedy growth. But it might also apply to the US; after all, it’s what can happen when you slip. |